People in Economics

The Man with the Patience to Cook a Stone

Finance & Development, September 2012, Vol. 49, No. 3

F&D profiles Justin Yifu Lin, the first World Bank Chief Economist from a developing or emerging economy

At a reception earlier this year to mark the end of Justin Yifu Lin’s tenure as chief economist of the World Bank, as is customary on such occasions, there was mention of a lifetime of achievements: Justin Lin, the first Chinese of his generation to receive a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago; Justin Lin, the second private citizen to own a car in Beijing; Justin Lin, the first person from a developing country or emerging market to serve as World Bank chief economist.

Alongside these milestones were tributes to his most defining qualities: his determination, his flexibility, his pragmatism. Most memorably, one of his colleagues said, drawing on an African proverb, Lin had patience that could cook a stone.

If ever a person qualified for the description of “right man, right place, right time,” Lin is that man. His qualifications include his arrival in mainland China just as—fortuitously for him—the Communist Party was launching a series of historic market reforms. Then, a serendipitous pairing of Lin’s English language skills with a visiting Nobel Prize–winning economist in need of a translator ended with Lin’s nomination for a scholarship to pursue a Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. And in June 2008, just before the world headed into the worst recession in over half a century, amid increasing clamor for emerging and developing countries to have a greater say in the running of the World Bank, Lin was selected its chief economist—the first person from a developing country to hold the post. The tide of history has been generous to the 60-year-old Lin.

Rethinking development

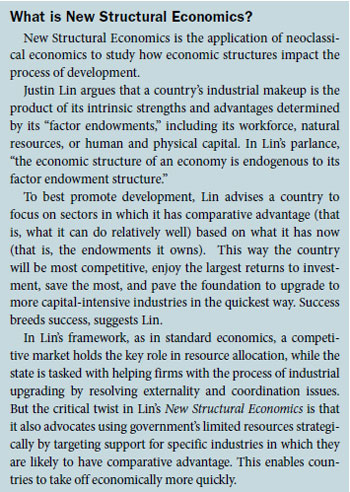

Fast-forward four years, and Lin is preparing to return to China after his sojourn in Washington, D.C., home of the World Bank, of which he was also a senior vice president. This intensely private, bespectacled economist contemplates the latest stage of his eventful career with a sense of quiet satisfaction. The Bank gave Lin a global platform to push his framework for rethinking development—or, as he terms it, New Structural Economics (see box).

“I opened the door for people to think, for my colleagues to think, to debate,” he says.

Lin, an expert on China’s economy, views himself as semi-detached from the Western-based policymaking circles that have historically dominated development economics. As World Bank chief economist, Lin followed in the footsteps of luminaries such as former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz. But his theories are a deliberate and sharp critique of the Washington Consensus, the broad range of “neoliberal” policies previously closely associated with Washington D.C. institutions, including the IMF, the U.S. Treasury, and the World Bank. When asked to confirm whether he was indeed the first World Bank chief economist from a developing country, Lin responds, “Not only the first from a developing country, but also [the first] to have a good understanding of developing countries.”

According to Célestin Monga, Lin’s coauthor and World Bank colleague, Lin is “the one guy in the history of all the chief economists at the World Bank who has actually been part of the lifting out of poverty of 600 million people. Do you need anything else?”

Stiglitz says Lin played a major role in marrying the lessons of growth in east Asia, the fastest-growing region of the world, with development economics.

Model army officer

Lin’s modest background—he was born one of six children into a poor family in Yilan County, northeastern Taiwan Province of China, in 1952—may distinguish him from his predecessors, but undoubtedly he is the only World Bank chief economist with an arrest warrant hanging over his head.

In 1979, the 26-year-old, who then went by the name Lin Zhengyi, a model officer in the Taiwanese army stationed on the politically sensitive island of Kinmen, decided to swim across the 2,000-meter tidal strait to the Communist-controlled mainland to start a new life.

Following his disappearance, the Taiwanese authorities who declared him “missing” compensated his wife with the equivalent of more than $30,000; much later, they charged him with desertion.

Ask Lin about his decision today and the economist bats away further inquiries—the only time during the whole interview his ever-present smile freezes and he betrays a hint of irritation. Lin left behind his three-year-old son and wife, Chen Yunying, who was then pregnant with their daughter. Asked about his wife’s reaction to his defection, Lin says,

“She supported me. As long as I am happy, she is happy.”

“So did you tell your wife you were going to leave?”

“I implied that.”

Transforming China

When he arrived on the mainland, Lin changed his name to Lin Yifu, meaning “a persistent man.” Unable to contact his family directly, Lin sent a letter to a cousin in Tokyo describing his loneliness and longing for his wife and children. Alongside prosaic domestic details—including a request that his cousin send Christmas presents on his behalf to his family using Lin’s secret nickname—are descriptions of a China at a critical juncture in its development as it sought to transform itself from a centrally planned to a market economy:

“Now, China is examining the 30 years since the founding of the People’s Republic in a serious and honest manner—and trying to learn from its mistakes—in order to build a modernized China. Ever since the Gang of Four was overthrown, the entire mainland has been advancing by leaps and bounds; people are full of aspiration and confidence. I strongly believe that China’s future is bright; one can be proud to be Chinese, standing in the world with one’s head held high and chest out,” he wrote.

China and other countries—most notably in Asia—that have made the leap from underdevelopment and widespread poverty are core exemplars of Lin’s thesis of development. In his New Structural Economics, Lin argues a prescription for underdeveloped countries that could crudely be summarized as “make the best of what you’ve got.”

A key tenet of his “new framework for development” is the critical role of government in supporting selected industries in order to trigger structural transformation. This practice, often colloquially referred to as “picking winners and losers,” or industrial policy, has had a checkered history, but in the aftermath of the financial crisis has been enjoying something of a revival.

The leading criticism remains that the government’s imperfect judgment and distorted interests displace the cold, clear decisions of the market. For example, Japan’s much-lauded Ministry of Trade and Industry once opposed the plans of domestic car manufacturers to export and tried to prevent Honda expanding from motorbikes into cars because it did not want another company in the industry.

To avoid such mistakes, the secret of success, suggests Lin, is identifying industries appropriate for a given country’s endowment structure and level of development. He points to Chile, for example, which moved from basic industries such as mining, forestry, fishing, and agriculture, to aluminum smelting, salmon farming, and winemaking, with the backing of the government. Lin says, in the past, industrial policy often failed because government tried to impose the development of industries that were ill-suited to the country’s endowment. That is, they “defied” their comparative advantage.

Lin’s choice of New Structural Economics as the appellation for his theoretical framework has resonances of Structuralist economics—referred to by Lin as the first wave of development thinking—which emerged in Latin America in the 1940s, with its support for government intervention to promote development. But the World Bank’s regional chief economist for Africa, Shantayanan Devarajan, believes the intellectual origins of Lin’s New Structural Economics lie closer to home, and in the more recent past.

Earlier this year, at a seminar to mark the launch of Lin’s new book outlining his thesis, Devarajan opened the proceedings with the provocative salvo: “When I saw the title New Structural Economics, I was reminded of what Voltaire said about the Holy Roman Empire. ‘That it was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.’ So I am going to challenge Justin to convince us that this is new, that this is structural, that it is economic.”

Devarajan is skeptical about the originality of Lin’s thesis, which, he says, is “the quintessential application of neoclassical economics to development. Because neoclassical economics says markets should operate unless there is a market failure, like an externality. If there is an externality, then government should intervene to fix that externality.”

Lin acknowledges a debt to neoclassical economics while maintaining that the critical and large role given to government makes his theory distinctive. If the Washington Consensus is the second wave of development thinking, he regards his approach as the third, or “Development Thinking 3.0.” His work “challenged economic convention,” said Uri Dadush, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

A new book by Lin, The Quest for Prosperity, explains new structural economics and reflects lessons learned from four years at the World Bank. By following this framework, Lin shows how even the poorest nations can grow rapidly for several decades, significantly reduce poverty, and become middle- or even high-income countries in the span of one or two generations. “Lin dares to envision the end of world poverty,” says Nobel laureate George Akerlof.

The problem of comparative advantage

Some of Lin’s precepts appear deceptively intuitive. It might seem obvious that countries should play to their strengths. But would Lin, given his directive that countries focus on their underlying comparative advantage, have recommended that Korea create a ship-building industry in the 1970s considering the country’s limited domestic supply of raw materials such as iron, coal, and steel, and the lack of any knowledge of the sector? Some other economists doubt it. And yet that was Korea’s successful recipe for development.

“Given the nature of the process of factor accumulation and technological capability-building, it is simply not possible for a backward economy to accumulate capabilities in new industries without defying comparative advantage and actually entering the industry before it has the ‘right’ factor endowments,” says Cambridge University professor Ha-Joon Chang.

The strong imprint of neoclassical economics in Lin’s framework is perhaps unsurprising: he trained at the University of Chicago. His admission to the citadel of free-market thinking was another example of the happy good fortune that has periodically blessed his existence. Within a year of his arrival in China, by dint of his English language skills learned in Taiwan, Lin was recruited as a translator for visiting economist Theodore Schultz. Schultz had, that year, been awarded the Nobel Prize for economics for his pioneering research into the problems faced by developing countries.

So impressed was Schultz with his young interpreter—who was by then studying Marxist economics at Peking University—that on his return to his teaching post at the University of Chicago, Schultz offered to arrange a scholarship for the young Lin.

How long did Lin spend with the top economist to have elicited such a generous offer? Just one day, “but I was a very impressive translator,” says Lin. His smile does not waver. Schultz had a reputation for intuitively identifying young talents, having mentored Nobel laureate George Stigler and a former president of the American Economic Association, D. Gale Johnson, for example.

Once enrolled at Chicago, the young Lin embarked on a Ph.D. in economics. He was later joined by his wife, Chen Yunying, and two children. While Lin studied for his Ph.D., and then went on to Yale as a postdoctoral student, his wife earned a Ph.D. at George Washington University.

Prolific career

When Lin and his family returned to Beijing in 1987, China was in the throes of an economic revolution, transforming itself from a centrally planned to a “socialist market economy.” Against the backdrop of state-owned enterprises being carved into smaller private businesses, the decollectivization of agriculture, and the creation of special economic zones, Lin embarked on a prolific career. Even before he joined the World Bank, he had authored 18 books and numerous papers.

In 1994 Lin helped found the China Center for Economic Research (CCER) at Peking University, set up to attract foreign-educated Chinese brains at a time when the country was thirsting for knowledge about how to harness its economic potential. The center became increasingly influential in the shaping of Chinese economic policy.

Lead economist

Lin’s chief economist and senior vice president position at the World Bank—he was selected by the organization’s President Robert Zoellick—meant he was chief economic advisor to the World Bank president, spokesperson for the Bank’s development policies, and head of the Bank’s research, prospects (global monitoring and projections), and data departments. In that role, he led almost 300 economists, statisticians and researchers tasked with reducing poverty and promoting global development.

He earned a reputation as a hard worker and canny operator. “He always has his game face on,” said one colleague, Monga, who accompanied Lin on many business trips. He described how Lin, rather than socializing after a day’s work would labor long into the night. “Justin was all about work,” he said.

Inevitably, the experience of serving as chief economist was not without its challenges. Lin encountered internal dissent about his views, often with strong opposing opinions coming from within the research department that he supervised. Lin says he listened to disagreement, but some staff at the Bank say he largely sidestepped them. “He didn’t try to shape it or mold it any which way; he just separated himself. And I think that was less productive than it could have been,” said one high-level economist at the Bank.

To ensure that his work on development economics made a mark on the Bank, Lin set up a research team to work on industrialization in Africa, which he sees as ripe for growth. As emerging markets such as China, India, and Brazil move up the industrial ladder and “graduate” from low-skilled manufacturing sectors, he argues, it will open up opportunities for low-income countries in Africa and elsewhere to get into those sectors. “This will free up a gigantic reservoir of employment possibilities that African and other low-income countries can tap into,” Lin said. But African countries need to plan for this handover.

Hassan Taha, an executive director at the Bank who represents 21 African countries, says Lin “encouraged an evolution in thinking” that helped developing countries better tackle the challenge of poverty reduction.

Return to Beijing

Lin has now returned to Beijing to resume teaching at the CCER. While grateful for the opportunities that his position as chief economist offered him, Lin said he was eager to return to China after getting a bird’s-eye view of global development from Washington. His personal and professional love of China would preclude any long-term separation.

Perhaps only one place continues to be an elusive attraction. At a seminar organized by the Center for Global Development in Washington just weeks before the end of his stay in the U.S. capital, Lin revealed he still harbored a “dream” to return to Taiwan Province of China to pay tribute to his ancestors and meet relatives and friends.

In 2002, following the death of his father, Lin applied to return for the funeral. The authorities approved his application, but the army issued an order for his arrest for desertion—an order that has yet to be lifted. Consequently, Lin was represented by his wife at his father’s funeral—a serious shortcoming for an Asian son.

Lin maintains that the island will eventually be reunited with the mainland.

So far, appeals by his supporters to have his arrest warrant lifted have fallen on deaf ears. Earlier this year, in answer to a parliamentary question, Taiwan’s Defense Minister, Kao Hua-chu, who was Lin’s battalion commander and a close friend, told the legislature’s Foreign and National Defense Committee that he would resign in protest if Lin did not face the charge upon returning. In response, Lin said he can wait.

Lin’s legendary patience is set to be tested for a while longer. ■