People in Economics

Second Time Around

Finance & Development, December 2011, Vol. 48, No. 4

![]() Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala on a different Africa

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala on a different Africa

Jeremy Clift profiles Nigeria’s economic czar Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala

AMID the drab suits of international finance, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s colorful and vibrant traditional African attire always guarantees she will stand out in a crowd. Often wearing a coordinated head wrap, Okonjo-Iweala is a big personality with matching opinions. “I feel very Nigerian, very African, and I love it,” she says.

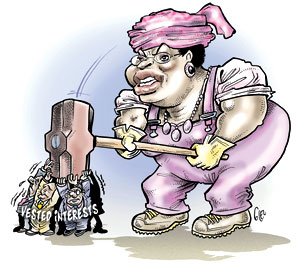

The daughter of two university professors from the Niger Delta region, she has a reputation for no-nonsense straight talk and tough action that has won her the nickname Okonjo-Wahala, or “Trouble Woman,” from both critics and legislators back home because of her zeal for reform.

Appointed to the job of coordinating minister in charge of all economic ministries, she has the unenviable job of revamping the economy of Africa’s most populous country. One in six Africans is Nigerian, and in a very real sense much of the future dynamism of the continent will be determined in the Nigerian capital.

Africa, says Okonjo-Iweala, has no time to lose. “We, as countries, need to run faster if we are not going to fall behind in this global race.”

Tough negotiator

It’s second time around for Okonjo-Iweala, who has taken on the demanding job of Nigeria’s economic czar, giving up her position as a managing director at the World Bank in July 2011 to return to the capital of Abuja for the second time in a decade.

As managing director, she negotiated a $49.3 billion funding package last year for the International Development Association (IDA), the Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, which plays a key role in working toward the UN Millennium Development Goals.

She had earlier served as Nigeria’s finance minister and then briefly as foreign affairs minister from 2003 to 2006—the first woman to hold either position. During her first government stint, she worked to combat corruption and entrenched vested interests, increase financial transparency, and institute reforms to make the economy of Africa’s largest oil exporter more competitive and more attractive to foreign investment. She also struck a deal in 2005 for debt relief worth $18 billion from bilateral creditors and secured the country’s first sovereign credit rating.

Hardship and malaria

Okonjo-Iweala traces her resilience and determination to her childhood. She grew up partly under British colonialism and later during the devastating Biafran war, when pictures of starving and sick children grabbed world headlines.

“I have lasting memories of children dying around me,” she told F&D in an interview.

Up to three million people may have died during the civil war and military blockade, mostly from hunger and disease. A daughter of privilege—her father is the traditional Igbo ruler, or Obi, of Ogwashi-Uku in southeast Nigeria—the young Okonjo-Iweala worked with her mother, Kamene, in a soup kitchen for the troops.

Her father, Chukwuka Okonjo—a retired professor of economics—joined the breakaway Biafran army as a brigadier. “Basically, we ran from place to place and my parents lost everything, everything they owned—all their household belongings, all their savings,” she remembers. “I spent some time in Port Harcourt with my mother, and we would cook for the armed forces. We spent all day doing that. That was our way of contributing. We had no meat for three years. We couldn’t go to school until the last year of the war, when my mother set up a little school.”

Before the civil war, Okonjo-Iweala lived for some time with her grandmother in a Nigerian village, while her parents were studying in Germany. “She was very loving but also liked discipline. I had to fetch water from the stream with other children before going to school, do the chores, and go to the farm with my grandmother. I think first growing up in the village and having that type of focus and discipline—and then growing up during the war—made me very hardy, able to survive in very difficult conditions.”

Okonjo-Iweala tells how during the civil war, while her mother was ill and her father away in the army, she rescued her three-year-old sister who was sick with malaria and at death’s door. She put her sister on her back and walked 10 kilometers to a clinic in a church, where she’d heard there was a good doctor. When she arrived, there were a thousand people outside, trying to break down the door. Undeterred, she crawled through their legs with her sister on her back and climbed through the window to see the doctor. “I knew if she didn’t get help she’d die,” says Okonjo-Iweala.

The doctor gave the girl a shot of chloroquine and put her on rehydration therapy, and within hours she was back to health. The injection saved her sister’s life. “The 10 kilometers home with her on my back, that was the shortest walk of my life. I was so happy,” she said.

She has shown the same pluck and determination ever since.

Battling vested interests in Nigeria

When she was appointed to head Nigeria’s economic management team, she and Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, co-winner of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, were portrayed on the cover of Africa Report magazine as two of Africa’s Iron Ladies who are spearheading change.

One of Okonjo-Iweala’s first moves was to slash red tape in Nigeria’s ports, cutting the number of federal agencies working there from 14 to 6. Other sacred cows, such as fuel subsidies, are also on the chopping block, but reforming the tangled web of poverty, kickbacks, extortion, mismanagement, and ethnic tensions is difficult.

While many laud her drive for reform, critics argue that her determination to slash fuel subsidies, for example, shows she is blind to the interests of the man in the street, who benefits from the lower gasoline price.

Nigeria, with a population of 158 million, is the largest country in Africa, is its biggest oil exporter, and has the largest natural gas reserves on the continent; but more than half the population still lives in grinding poverty, hobbled by power outages, poor roads, and corruption. Despite the problems, the country is home to the largest movie industry in Africa, producing the second largest number of video releases in the world after India and ahead of Hollywood.

“What do we need to do? Our priority in the present budget is first and foremost security. Second is infrastructure, infrastructure, and infrastructure because this is one of the bottlenecks to making the other sectors in the economy work. We also need power, roads, and ports,” says Okonjo-Iweala, who coordinates the country’s economic agenda.

“We launched port reforms recently; we tried to bring down the cost of going through our ports and saving people the stress that it entails, like taking three to four weeks for clearance of goods. We tried to bring the clearance period to one week and even less, halving the number of agencies at the ports and trying to deal with the corruption, extortion, and other things that go on there, to bring the cost of doing business down.”

Steady hand

Box 1. Accidental major

At Harvard, Okonjo-Iweala studied economics. “It was an accidental major,” she says. “I was a top student in geography at school and very interested in regional and spatial issues and their impact on development. So I applied to study geography at Cambridge, England. When I, with my family, decided I should go to Harvard, I just assumed this would be a subject there I could major in.”

To her consternation, she found on arrival in Massachusetts that Harvard had no geography major.

“When I described my interests to some tutors they said the closest major that mirrored my interests was economics, so there it was. I ended up with that and went into regional economics for graduate school. We were the ones who studied the now forgotten input-output economics of Wassily Leontief, the Nobel Prize winner, and social accounting matrices—which are still used.”

All four of her children have also studied at Harvard.

Colleagues say she always had star power. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1976 (see Box 1) and holds a Ph.D. in regional economics and development from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1982 she joined the World Bank, where she worked until July 2011 (except during 2003–07, when she was first in Nigeria and later a consultant), rising through the ranks and eventually becoming a managing director.

Affable, approachable, and hardworking, she was known for her rigor and strong technical knowledge. “I would say she is an eternal optimist and a straight shooter,” says Tijan M. Sallah, who currently heads the Capacity Development and Partnerships Unit for Africa in the World Bank and who wrote a book with Okonjo-Iweala (see Box 2). “She is also a strong advocate for women,” he adds, pointing to her efforts to help promote promising young women into managerial positions in the World Bank. She also helped set up a private equity fund to invest in African women–owned businesses.

She thrives on hard work, cramming appointments into the day. But her flexible approach to time is not for everyone. “I am the type of person who likes to get to the airport two hours before takeoff,” says her spokesman, former journalist Paul Nwabuikwu. “She is the type who will show up when there are only five minutes to go,” he told Africa Report.

Others welcome her steady hand. “Despite the fact that she works incredibly hard, and long hours, Ngozi is always calm and collected—never flustered—which is extremely valuable in the mad rush that characterizes the development business,” says Shantayanan Devarajan, chief economist for the Africa Region at the World Bank.

Development economics

Box 2. Chinua Achebe “My hero”

When Okonjo-Iweala couldn’t find an inspirational book on African heroes for her eldest son while her family was living in Washington D.C., she decided to write her own, in what turned out to be an eight-year project on Chinua Achebe, the well-known Nigerian writer and activist.

“My oldest son loved nonfiction biographies as a child and adolescent, but all the books I could find were on American and British heroes, none on African heroes.” She teamed up with Tijan Sallah, an economist and writer from The Gambia, to write a series on influential Africans.

But the first book took so long that so far they have written only about Achebe, author of an acclaimed 1958 English language novel on Nigeria, Things Fall Apart. “He is someone who made African culture accessible,” says Okonjo-Iweala. “I knew him personally. He is an African who could tell our own stories—simple and direct but at the same time so elegant.”

On the day of the book launch, Sallah says, he got a call from retired former U.S. Secretary of Defense and World Bank chief Robert McNamara, asking the location of the Ngozi event. “I knew Ngozi’s magic and brand were at work,” he said.

Okonjo-Iweala’s son Uzodinma Iweala is the author of the novel Beasts of No Nation, about a child soldier in west Africa.

Sallah, Tijan M., and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, 2003, Chinua Achebe: Teacher of Light (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press).

Nigerian critics say that her Harvard education and the amount of time she has spent abroad have given Okonjo-Iweala an overly Western perspective and that she is intent on ramming through difficult reforms when security is under stress. A development economist for more than two decades, Okonjo-Iweala has been responsible at various times for programs in countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. She says ideas about development have evolved and gone through several phases.

“I look at it more from the practitioner’s viewpoint because most of my career was at the World Bank.” When she started out, she says, there was a feeling that all the answers lay out there, in the field. “The whole theory of savings and investment and lack of capital—and if you could just fix that, then the countries would be able to develop.

“When that didn’t quite work, the focus shifted to lack of capacity. If you just built up capacity through technical assistance, then all the problems would be solved. But they weren’t solved. So we had rather a one-dimensional approach, particularly to Africa, for quite a long time.”

In that respect, the findings of the Growth Commission, headed by Nobel laureate Michael Spence, were a breath of fresh air. “The admission that there is no one all-perfect answer on the issue of growth and development, that there is good practice and bad practice and we should learn the good lessons and keep away from the bad, and that there is no one magic bullet—it’s very humbling and helpful,” says Okonjo-Iweala, who was one of the commission’s 22 members from around the world. It published its final report in 2008.

But certain things have been consistent, including the emphasis on a strong and stable macroeconomic framework as the bedrock for the development of the real sector. “Without a stable and functioning macroeconomic environment, you really cannot move in a sustainable fashion. The lessons about implementing basic prudent fiscal policies and sensible monetary and exchange rate policies—looking at your competitiveness and keeping that in view, which means that you really have to adjust continuously. Adjustment is not a one-time thing: it is something that you do all the time to manage the economy and that you have got to do to maintain policy consistency.

“Learning those lessons has taken a number of years.”

She says Africa wasted a lot of time—during the “lost decades” of the 1980s and 90s in particular.

“What is really interesting to me is that after those lost decades, African countries have really learned the lessons, and that has helped them to do much better in the economic and financial downturn of 2007—until now.

The next BRIC?

The next BRIC?

Drawing the right conclusions has helped put sub-Saharan Africa on a growth path, even during the current global turmoil.

So much so that when she was still at the World Bank, Okonjo-Iweala began talking about Africa as the next BRIC—referring to major emerging markets, such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China. “What trillion-dollar economy has grown faster than Brazil and India between 2000 and 2010 in nominal dollar terms and is projected by the IMF to grow faster than Brazil between 2010 and 2015? The answer may surprise you: it is sub-Saharan Africa!” she told an audience at the Harvard Kennedy School in May 2010.

To turn the BRIC vision into a reality, sub-Saharan Africa needs to grow even faster than it did before the global financial crisis. A big push to build infrastructure is part of the solution.

As in Nigeria, lack of adequate infrastructure, she says, is one of the big factors holding Africa back. Africa’s poor roads, ports, and communications isolate it from global markets, and its internal border restrictions fragment the region into a myriad of small local economies. It is neither regionally nor globally integrated.

The problem is how to pay for that infrastructure. Okonjo-Iweala suggests that major donor countries could issue African Development Bonds on the New York market to provide the financing. “Most importantly, issuing a bond like this could change perceptions overnight about Africa as a place to do business. Faced with secure financing of $100 billion, private firms across the world would line up to provide infrastructure in Africa,” she predicts.

Together with better underlying economic policies, Okonjo-Iweala predicts that a rising middle class in Africa will fuel growth.

“We don’t want to exaggerate it, but you can definitely see that it is there. That gives a bedrock from which one can talk about investment, purchasing consumer goods, to see the continent as an investment destination. Not just for exports but also for the consumer market. If you look at what has happened in the telecommunications revolution in Africa, then you would really know that things are changing. In Nigeria, we now have 80 million phone lines. Within living memory, about 11 years ago, we had just 450,000 land lines. This is changing the way that business is done. It is changing the way development is done and is going to be done in the future.”

Jobs for the young

She believes private sector growth will underpin job creation. “The biggest issue on the continent now is jobs for young people. If you look at the demographics, you will see that in most African countries 50 to 60 percent of the population is 25 and under. With that realization, you have millions of youth coming on the job market.”

One way of stimulating the private sector is to encourage large numbers of well-educated Africans abroad to come home. “You cannot wait as a diaspora person for everything to be OK, for the economy to be better, for security to be perfect. You can’t wait for everything to come together.

“We need them back because they can be the bedrock and the backbone of development in many of these countries. Nigeria, for example, has thousands of doctors in the United States, but here we are badly in need of proper medical care,” says Okonjo-Iweala. “We keep sending people abroad for treatment, so why can’t these doctors come back and set up? Why should we spend precious resources sending people abroad with complicated cases? We need those skills.”

At the same time, receiving countries need to make sure Africans coming home are welcome, and not treated with envy or suspicion.

Not for those with thin skins

Returning to Nigeria elicits a combination of emotions for Okonjo-Iweala. “It feels right, it feels joyful, but it’s also frustrating. There is so much to do.”

“I have a president who really wants change,” she says, referring to Goodluck Jonathan, who won the presidential election in April this year. “But we have a long way to go. We have a lot of challenges to meet. We are working on so many programs that we need to correct. But so long as the political will is there, then you just take it one by one.

“There are a lot of vested interests, a lot. They are not just going to allow you do everything without fighting back. And the way they fight back isn’t necessarily nice and neat,” she says. “On the Internet, they put up all kinds of stories about me or they attack in different ways. What they are trying to do is either take you down or bring your reputation down, because we are trying to correct a few things. So it is not a pretty game. Not a game for those with thin skins or weak stomachs.” ■