Straight Talk

Emerging Challenges

Finance & Development, June 2011, Vol. 48, No. 2

Emerging markets must adapt to the new global reality by building on their economic success

In THE WAKE of the recent crisis, a two-speed recovery shifted global economic growth from advanced to emerging and developing economies.

While gross domestic product (GDP) in advanced economies grew on average 3 percent in 2010, emerging and developing economies grew 7.2 percent. The IMF forecasts that the two-speed trend will continue this year. Advanced economies are projected to grow 2.5 percent and emerging and developing economies 6.5 percent, their consumption surging too. In absolute terms, emerging and developing economies will consume $1.7 trillion more in goods and services this year than last year.

Naturally, the rapid growth in emerging markets is swiftly lifting their importance in the global economy. They account for nearly two-thirds of the total growth in global output in the past two years, compared with one-third in the 1960s. Their contribution to foreign trade is also large and increasing, even though advanced economies trade almost twice as much.

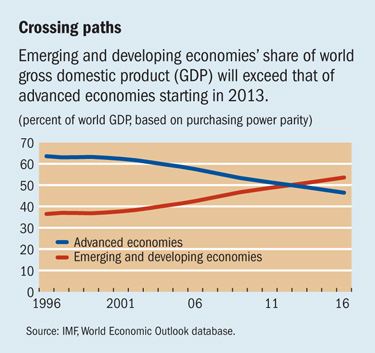

The growing heft of emerging market economies is part of a long-term trend. In each of the past five decades, the growth rate of emerging and developing economies exceeded that of advanced economies—at times by a large margin. As a result, at the end of last year emerging and developing economies accounted for 48 percent of global output (measured in terms of purchasing power parity—using the exchange rate at which the currency of one country must be converted into that of another country to buy the same amount of goods and services in each country).

The trend may well continue for a while (see chart). The overall economic conditions in emerging economies are quite favorable: relatively small fiscal deficits, manageable public debt, stable banking systems, low cyclical unemployment, and strong growth momentum. In contrast, many advanced economies are facing serious challenges that stem from big government deficits, large public debt, problems in their banking systems, high unemployment rates, and weak growth. In addition, recent structural changes in emerging economies support the three key drivers of growth: the labor force is growing at a rapid pace and populations are urbanizing, investment is growing with support from ample foreign capital, and productivity is increasing as production moves up the value-added chain. If current trends continue, in two decades annual global output will more than double, from $78 trillion to $176 trillion (in today’s money), of which $61 trillion in additional output will come from emerging and developing economies, while advanced economies’ contribution will be about $37 trillion.

Major shifts in global economy

Strong demand and supply growth are taking place in economies whose populations are much bigger than those of advanced economies. Three billion people live in Brazil, Russia, India, and China—the so-called BRICs—alone, compared with 1 billion in advanced economies. When all emerging and developing economies are combined, they account for 85 percent of the world’s population. Incomes of large numbers of people are rising rapidly and causing tectonic shifts in major aspects of the global economy:

• Food: Global demand for food is rapidly rising as large numbers of people enjoy higher per capita incomes, allowing them to buy more nutritious foods. Demand is rising for basic foodstuffs and for food products with higher value added.

• Nonfood commodities: The need for better housing and transportation and more energy is placing tremendous upward demand pressure on nonrenewable resources, such as petroleum and metals. The numbers are staggering. During the past 10 years, while global oil consumption increased by 13.5 percent, oil consumption in emerging markets increased by 39 percent—and their share of global consumption grew from one-third to one-half. And almost all the additional global demand for copper, lead, nickel, tin, and zinc came from major emerging market economies. During the next five years, for example, emerging markets’ share of global copper consumption is projected to jump to three-quarters from only one-third a decade ago.

• Capital flows: Although emerging and developing economies account for almost half of world GDP, they hold only 19 percent of world financial assets. As money chases growth and opportunity, global financial and capital flows are shifting toward emerging market economies. The movement of only 1 percent of financial assets in advanced economies into emerging markets is equivalent to the current flow of foreign direct investment from advanced economies into emerging markets. Indeed, capital flows from the United States to emerging markets increased from an annualized $300 billion during 2006–07 to an estimated $550 billion in 2010, while flows to advanced economies declined from $900 billion during 2006–07 to $600 billion in 2010. Strong capital inflows are putting upward pressure on consumption and asset prices in emerging markets, and risk is building in the financial sector.

• Patterns of production: Global manufacturing production patterns are shifting. Emerging market economies are producing more high-technology machinery and equipment, and low-technology manufacturing is increasingly moving to lower-income countries.

• Trade: Global trade patterns will gravitate toward emerging markets. Emerging market economies’ strong growth both in production and in domestic consumption will lead to more trade with advanced economies and, notably, among themselves.

• Environment: The toll on the environment is growing. Pollution is visible in the air and water, and the potential consequences will be devastating if the world does not reduce its carbon footprint.

Broad changes needed

Only with deep structural changes in growth models, policies, and lifestyles can emerging market economies address the long-term challenges they face.

A growth model that depends on demand from advanced economies will no longer serve emerging markets well. Emerging markets should shift their focus from growth led by external demand to internally generated, supply-driven growth. Policies should follow and pay particular attention to the supply side. Emerging markets should take the following steps:

• Make every effort to continue increasing their agricultural output to cope with the surge in demand for food. This will require not only supporting investment in agriculture, but also encouraging research and development to promote innovation and productivity growth in the agricultural sector.

• Pay particular attention to their service sector, because it creates employment at a sustainable pace. Policies should be geared toward opening, not closing, markets to competition, as has been customary in many economies. In particular, governments should refrain from excessively protecting small businesses, at the expense of consumers. In particular, governments should actively dismantle monopolies so that anyone who wants to enter a market can do so, which would boost efficiency and reduce price pressures.

• Invest heavily to eliminate bottlenecks. For the government this means investing in infrastructure, especially in transportation and energy, and ensuring entry and exit to all markets so that firms can take advantage of business opportunities. This also means educating and training workers to increase efficient use of capital and to boost household incomes. Investing in the application of established and new technologies will also help boost productivity.

Macroeconomic stability is paramount for other policies to work effectively. So emerging markets need to maintain strong fiscal, financial, and external buffers and implement good macrofinancial policies. Emerging markets must also continually improve institutions with a view to designing and implementing better policies.

There are two areas I think are critical for the future of emerging markets: building viable pension and health care systems and reforming financial systems. As populations grow, pension systems in most emerging markets will put an undue burden on the next generation or, if benefits are reduced, risk pushing large pockets of the population back into poverty. Similarly, major reforms are needed to broaden access to higher-quality health care. There are both successful and unsuccessful examples of pension and medical care reform in advanced economies, and emerging markets should learn from these examples and design systems to fit their own circumstances.

Emerging markets should also reform their financial systems, which are at the center of economic activity—channeling countries’ savings into investment, which is the key component of growth. Financial institutions also play an important role in facilitating capital flows from abroad, which are expected to remain strong in the medium term in response to favorable growth opportunities in emerging markets. Reforms are needed to ensure that the financial sector serves the economy rather than the other way around and that losses are not socialized while gains are privatized.

Finally, and perhaps most fundamentally, there is a need to foster a lifestyle that is more respectful of the earth and its finite resources. For example, most of us need to use less energy, use it more efficiently, and produce it more cleanly. We also need to be much more mindful of what we consume and how we consume it. It is very difficult to change such behavior, but governments can create the right incentives by pricing carbon correctly, including the environmental cost of our activities in the system of national accounts, and adding the true value of ecosystems into our national wealth calculations.

For most emerging and developing economies the past two years were great, and the future looks rosy. But there is no guarantee that the good times will last. In fact, that bright future will probably not materialize if the challenges I have outlined are not given priority and addressed satisfactorily. Modern history is replete with sobering cases of policy paralysis and ensuing lost years and decades. ■