Islamic Banking

Put to the Test

Finance & Development, December 2010, Vol. 47, No. 4

Islamic banks were more resilient than conventional banks during the global financial crisis

THE recent global crisis has renewed interest in the relationship between Islamic banking and financial stability—and, more specifically, the resilience of the Islamic banking industry during crises. Some argue that the lack of exposure to the types of loans and securities associated with the losses conventional banks experienced during the crisis—because of the asset-based and risk-sharing nature of Islamic finance—shielded Islamic banks from the crisis. Others contend that Islamic banks relied on leverage and took on significant risks, much like their conventional counterparts, making them vulnerable to the “second-round effects” of the global crisis.

Our study looks at the actual performance of Islamic banks and conventional banks in countries where both have significant market shares, and addresses three broad questions. Did Islamic banks fare differently from conventional banks during the financial crisis? If so, why? And what challenges for Islamic banks has the crisis highlighted?

Using bank-level data covering 2007–10 for about 120 Islamic and conventional banks in eight countries—Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—we focused on changes in four key indicators: profitability, bank lending, bank assets, and external bank ratings.

The Islamic banking model

The central concept in Islamic finance is justice, which is achieved mainly through the sharing of risk. Stakeholders are supposed to share profits and losses. Hence, charging interest is prohibited.

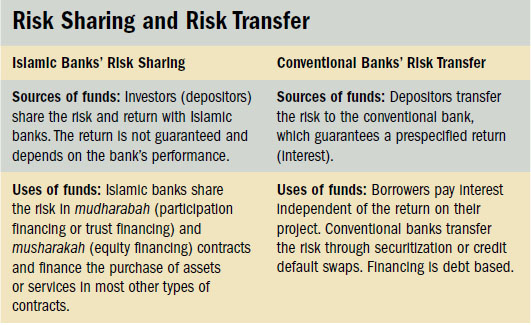

While conventional intermediation is largely debt based and allows for risk transfer, Islamic intermediation, in contrast, is asset based and centers on risk sharing (see table). “Asset based” means that an investment is structured on exchange or ownership of assets, placing Islamic banks closer to the real economy than conventional banks, which can create products that are mainly notional or virtual.

During the boom period of 2005 to 2007, Islamic banks’ profitability was significantly higher than that of conventional banks. During this period, real GDP growth for countries in our sample averaged 7.5 percent a year before decelerating to 1.5 percent during 2008–09. If this profitability was the result of greater risk taking, one would then expect a larger decline in profitability for Islamic banks during the crisis (defined in our study as beginning at end-2007).

We found that factors related to Islamic banks’ business model helped contain the adverse impact on this group’s profitability in 2008. In particular, smaller investment portfolios, lower leverage, and adherence to principles of Shariah (Islamic law)—which precluded Islamic banks from financing or investing in the kind of instruments (such as collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps) that adversely affected their conventional competitors—all contributed to better results for Islamic banks than conventional banks that year.

In 2009, however, weaknesses in risk management practices in some Islamic banks led to a larger decline in profitability than that seen in conventional banks. The weak 2009 performance in some countries was associated with sectoral and name concentration—that is, too much exposure to any one sector or borrower. In some cases, the regulatory authorities exacerbated the problem by exempting certain banks from concentration limits. (However, this concentration was limited to a few countries.)

While Islamic banks’ profitability over the business cycle (2005–09) was, on average, higher than that of conventional banks, the difference between the cumulative impact (2008–09) of the crisis on the profitability of the two groups was insignificant.

Contributor to stability

Islamic banks maintained stronger credit growth than conventional banks in almost all countries in the period studied—on average, twice that of conventional banks. This suggests that Islamic banks’ market share is likely to continue to increase—but also that Islamic banks made a greater contribution to macroeconomic and financial stability by making more credit available. Interestingly, while for most banks internationally, strong credit growth was followed by a sharp decline in credit once the crisis hit, this was not the case for Islamic banks. Because high credit growth is sometimes achieved at the expense of strong underwriting standards, we identified this as an area for supervisors to monitor.

The growth of Islamic banks’ assets likewise proved strong. We found that, on average, their asset growth was more than twice that of conventional banks during 2007–09, but it started decelerating in 2009, indicating that Islamic banks were less affected than conventional banks by deleveraging. The slower asset growth during 2009 could be attributable to the weaker performance of Islamic banks that year or to the fact that liquidity support in the form of government deposits is more easily directed to conventional banks.

Our findings were corroborated by external rating agencies’ reassessment of Islamic banks’ risk, which was generally found to be more favorable than—or similar to—that of conventional banks (with the exception of the UAE).

Challenges must be addressed

While the global crisis gave Islamic banks an opportunity to show their resilience, it also brought to light some important issues that will have to be addressed if Islamic banks are to continue growing at a sustainable pace.

Absence of a solid infrastructure for liquidity risk management. While Islamic banks rely more on retail deposits than conventional banks and hence have more stable sources of funds, they face fundamental difficulties when it comes to liquidity management, including

• a shallow money market due to the small number of participants; and

• the lack of instruments that could be used as collateral for borrowing or discounted (sold) at the central bank discount window.

Some Islamic banks have responded by running an overly liquid balance sheet (that is, having more cash-like assets that generate a lower rate of return than loans and many types of securities), thereby sacrificing profitability. Islamic financial institutions carry 40 percent more liquidity than their conventional counterparts (Khan and Bhatti, 2008). This approach to liquidity mitigated risks during the crisis, but it is not an ideal solution in normal circumstances. The establishment of the International Islamic Liquidity Corporation in October 2010 was a step toward enhancing Islamic banks’ ability to manage international liquidity. But such efforts need to continue.

More generally, monetary and regulatory authorities should ensure that the liquidity infrastructure is neutral to the type of bank (for example, by developing sovereign sukuk, or Islamic bonds, in addition to conventional bonds and certificates of deposits) and strong enough to address the problems highlighted during the global crisis.

Need for appropriate institutional arrangements for the resolution of troubled financial institutions. This is especially relevant for Islamic banks, given the absence of precedents. A mechanism for cooperation between regulators within and across jurisdictions for the resolution of Islamic banks is essential to contain spillovers beyond national boundaries.

Lack of harmonized accounting and regulatory standards. This proved a key problem for regulators and market participants during the crisis—one exacerbated by the lack of standard financial contracts and products across institutions. The standards for Islamic banks’ operations continue to be fragmented, despite initiatives by the Accounting and Auditing Organization of Islamic Financial Institutions and the Islamic Financial Services Board to create international industry guidelines.

Insufficient expertise. Expertise in Islamic finance has not kept pace with the rapid growth of the industry. Islamic bankers, regulators, and supervisors need to be familiar with both conventional finance and the different aspects of Shariah, given the increasing degree of sophistication of Islamic financial products. The shortage of specialists also inhibits product innovation and could hinder the effective management of risks particular to the industry.

In the recent global crisis, Islamic banks proved their mettle. But the crisis has led to greater recognition of the ways in which they still need to develop. As financial regulatory reform presses ahead on a global level, now is the time for the Islamic banking regulators to address the industry’s challenges. ■

Maher Hasan is a Deputy Division Chief in the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, and Jemma Dridi is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Middle East and Central Asia Department.

This article is based on the authors’ IMF Working Paper 10/201, “The Effects of the Global Crisis on Islamic and Conventional Banks: A Comparative Study.”