Asia Leading the Way

Finance & Development, June 2010, Volume 47, Number 2

Asia is moving into a leadership role in the world economy

THE recent crisis has underlined the emergence of Asia as a global economic powerhouse. Several dynamic economies in the region are generating growth outcomes that register on a global scale and are helping pull the world economy out of recession. China and India are leading the way, but the phenomenon is by no means limited to these two countries. Asia’s economic importance is unmistakable and palpable.

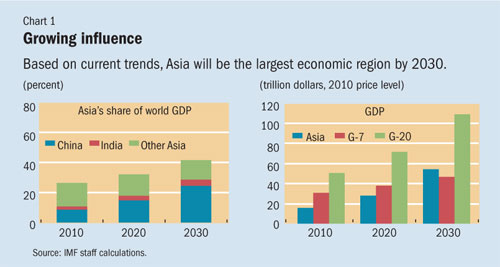

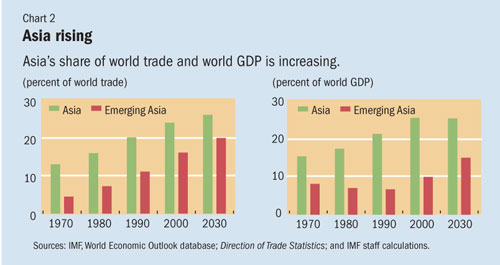

Based on expected trends, within five years Asia’s economy (including Australia and New Zealand) will be about 50 percent larger than it is today (in purchasing-power-parity terms), account for more than a third of global output, and be comparable in size to the economies of the United States and Europe. By 2030, Asian gross domestic product (GDP) will exceed that of the Group of Seven major industrial economies (G-7) (see Charts 1 and 2).

It is only natural, then, for Asia’s voice to become increasingly influential in global economic and financial discourse. Already, six of the Group of 20 major economies (G-20) are from the Asia-Pacific region. Asia accounts for just over 20 percent of IMF voting shares, and this weight is certain to rise as the IMF pursues reforms to bring countries’ voting shares more closely in line with their role in the world economy. With the right policies, this economic success is likely to continue and further improve living standards for Asian people, transforming the livelihoods of almost half the world’s population.

Consolidation of the recovery is still the main challenge for the world economy. Although Asia was not heavily exposed to the kinds of toxic securities that caused problems elsewhere, the region is an important participant in world trade, and its exports were hurt by the collapse in demand from advanced economies. The impact of the external shock was mitigated for countries with large domestic demand bases, such as China, India, and Indonesia, and some of the commodity producers, such as Australia, but the more export-oriented economies experienced particularly sharp downturns. However, economies across the region rebounded strongly, and by end-2009 output and exports had returned to precrisis levels in most of Asia, including in the hardest-hit economies.

New growth frontiers

At least two notable features mark the ongoing global recovery from Asia’s perspective. First, unlike in previous global recessions, Asia is making a stronger contribution to the global recovery than any other region. Second, also in contrast to previous episodes, recovery in many Asian countries is being driven by two engines—exports and strong domestic demand. Strong domestic demand reflects in part policy stimulus, but resilient private demand is also a factor. All this adds up to an impression that Asia is changing in key ways and that these changes have implications for the rest of the world.

Although there are still near-term risks in the outlook, in many ways, Asia is emerging from the recession with its standing in the world strengthened. The risks include Asia’s (and other regions’) vulnerability to renewed negative shocks to global growth and financial markets. Nonetheless, the possibility that Asia could become the world’s largest economic region by 2030 is not idle speculation. It seems very plausible, based on what Asia has already achieved in recent decades: emerging Asia’s share of world trade has doubled and of world GDP tripled in just the past two decades. In addition, the strengthened policy frameworks and institutions Asia has developed, particularly over the past decade, stood up well during the recession and provide a strong foundation for the future. Furthermore, in many countries in the region, populations are relatively young and will contribute to burgeoning workforces.

But by no means will rapid growth in the region continue automatically. Asia will need to build on its robust policy foundation with reforms to address the challenges the region still faces in both the near and the long term. In recent quarters, for example, Asia once again attracted a surge in capital flows as global investors responded to the region’s stronger growth prospects. The surge in capital inflows will need to be carefully managed to prevent overheating in some economies and to avert an increase in those countries’ vulnerability to credit and asset price cycles and macroeconomic volatility. However, the region could also be buffeted if shocks occur in global financial markets, as such shocks in the past have tended to affect emerging markets all across the world.

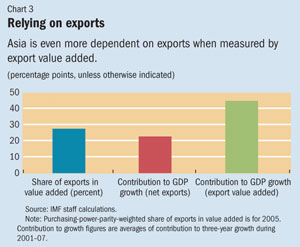

Over the medium term, a key policy challenge for many countries in Asia is to build on domestic demand, making it a more prominent engine of growth and relying less on exports (see “Deeper Markets, Cheaper Capital,” in this issue of F&D). This would also help manage global imbalances. More important, for many countries, the world recession has highlighted the unsustainability of tying growth too heavily to exports, which account on average for more than 40 percent of Asian growth (see Chart 3). With the recovery in advanced economies likely to be sluggish by historical standards, and their demand likely to remain below precrisis levels for some time, Asia will need to replace the shortfall in its external demand with a second, domestic source of demand if it is to sustain strong growth. Private domestic demand has contributed well to the recovery so far, but for it to continue it must be nurtured through policy. The policy measures will vary: some countries will need to increase consumption; some to sustain or increase investment, especially in infrastructure; and others must boost productivity in the service sector—all within the framework of greater trade integration in the region (see “Serving Up Growth,” in this issue of F&D). Many countries are already taking steps to improve and broaden the availability of social services, in addition to developing their financial sectors, which will help boost domestic demand. Greater exchange rate flexibility fits into this policy package by helping raise private consumption and reorient investment toward production for the domestic economy.

Policy challenges

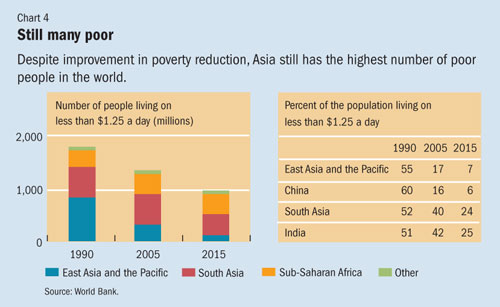

More broadly, globalization and the reform agenda still have far to go to bring all countries and populations into the fold. Asia has made unprecedented progress in poverty reduction in recent decades, with China alone having pulled some several hundred million people out of poverty since the launch of its reforms in 1978 (see “A Stronger China,” in this issue of F&D). Nonetheless, a high proportion of the world’s poor still live in Asia, and 17 percent of people in the east Asian and Pacific countries—40 percent in south Asia—live on less than $1.25 a day (see Chart 4). Moreover, the financial crisis has slowed poverty reduction in the region. The World Bank estimates 14 million more people in Asia will be living in poverty in 2010 as a result of the crisis. It is thus more important than ever to design and implement strategies, including reforms that enhance growth and strengthen safety nets, to alleviate endemic poverty in the region. Part of the strategy for low-income countries must include ways to move from agriculture to manufacturing as the basis for long-term growth. This will require development of national and regional infrastructure to reduce transportation costs and foster the integration of such countries into regional supply chains.

Countries across the region are, of course, well aware of the challenges they face and are taking action on many fronts. Strengthened monetary and fiscal policy frameworks, efforts at boosting domestic demand, and deepening trade and financial linkages with other economies have been the focus of reforms. The development of infrastructure to boost the growth potential of economies is going ahead rapidly in many countries, with the help of innovative mechanisms such as public-private partnerships. Barriers to trade, including within the region, are being lifted in ways that will allow more people to enjoy the gains from international trade, including by providing new markets and customers for exporters from smaller economies. Asia is moving ahead rapidly to advance regional integration more broadly, including through intraregional groupings such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and ASEAN+3 (including China, Japan, and Korea) and across regions, such as through the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, with its emphasis on “open regionalism.”

Asia’s time has come. Its role in the world economy continues to grow—both in world trade and finance and in economic governance, through institutions such as the IMF—and it will grow further. Meanwhile, countries all over the world are interested in Asian successes in development and managing globalization. The region’s economies offer a broad range of experiences from countries at various stages of development and faced with different sets of challenges, and the broader global economy can draw from them a rich set of lessons.