PrefaceThis pamphlet focuses on the Technical Assistance Program of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It is part of a series that aims to describe key aspects of the activities and policies of the IMF for the general public. Further information on IMF Technical Assistance can be obtained from the IMF's Policy Statement on Technical Assistance, the IMF Annual Report, and the annual Supplement to the IMF Survey, all available on the IMF's website (www.imf.org). Details about the IMF Institute's work can also be accessed through the website. Jeremy Clift of the IMF's External Relations Department prepared this pamphlet, with contributions from staff working in the IMF's Office of Technical Assistance Management. Note to the Reader The IMF's Monetary and Exchange Affairs Department was renamed the Monetary and Financial Systems Department as of May 1, 2003. The new name has been used throughout the pamphlet. Abbreviations

ForewordProviding technical assistance to member countries—particularly developing countries and countries in transition—is among the IMF's most important jobs. Yet this major component of our work is relatively unknown to the public at large. While the IMF's lending in support of policy programs in crisis countries captures the world's headlines, its technical assistance rarely does so, although it plays a vital role in laying foundations for stronger economies and for a better future for the people of many countries of the world. The technical assistance provided by the IMF, which includes training for government and central bank officials, is recognized as an important benefit of IMF membership. It is provided mainly in the IMF's core areas of responsibility and expertise—public finance, central banking, economic and financial statistics, and related legal matters. IMF staff, together with experts from member countries, share with member governments and central banks approaches for improving the design and implementation of economic policy, as well as for building up local expertise and helping develop stronger institutions, with the aim of enhancing economic policy management. Over the years, our technical assistance agenda has evolved with the needs of our member countries. In the early 1990s, we sharply stepped up technical assistance to the formerly centrally planned economies to help them build the policy infrastructure and institutions needed for market-based economies. Since the mid- and late 1990s, we have increased our efforts to help countries meet the challenges posed by globalization, particularly by strengthening their financial and statistical systems. Also in recent years, the IMF has given added emphasis to integrating its technical assistance with the policy advice it provides in the course of its economic surveillance and lending activities. And we have increasingly been encouraging countries to identify their technical assistance needs and priorities in advance rather than waiting for problems to emerge. Working in partnership, the IMF and its members are thus taking a more proactive approach to the planning, prioritization, and delivery of technical assistance. Sharing, through our technical assistance program, the collective knowledge of the IMF and our membership is one of the main ways in which we are working to achieve a global economy that works for the benefit of all. Eduardo Aninat

|

Box 1 The IMF provides technical assistance and training mainly in six areas:

|

|

An IMF and World Bank team prepares to cross Mount Igman to assess reconstruction needs in Bosnia after a cease-fire in 1995. |

The IMF provides technical assistance, including training, to the governments and central banks of member countries and, in some cases, nonmembers and international organizations. Much of this assistance is given to countries implementing IMF-supported adjustment and reform programs—more specifically, to their main economic ministries, such as the finance and planning ministries, and the central bank.

In its first two decades, the IMF occasionally supplemented its standard country consultations with technical assistance on such matters as exchange rate management and the conduct of monetary and fiscal policies. But it was in the mid-1960s, when many newly independent countries asked for help in setting up their central banks and finance ministries, that the practice was formalized, with three new organizational units established primarily to provide specific types of technical assistance: the Fiscal Affairs Department, the Central Banking Service (now the Monetary and Financial Systems Department), and the IMF Institute. The technical assistance provided increased steadily over the following quarter-century, but in the early 1990s requests for such assistance surged when countries in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union began their shift from centrally planned to market-based economies. Later in that decade, to improve crisis prevention and resolution following the Mexican crisis of 1994–95 and the Asian crises of 1997–98, the IMF further stepped up its technical assistance as part of its efforts to strengthen the architecture of the international financial system. More recently, as part of the international community's drive to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism, the IMF took the lead in the design of a comprehensive assessment process to spot problems and began to provide technical assistance for remedial measures.

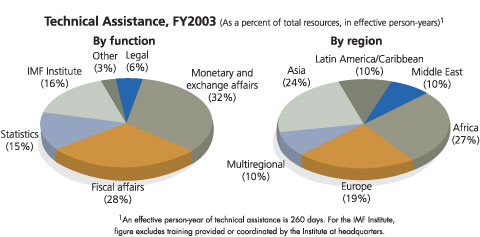

In recent years, the regional distribution of IMF technical assistance has gradually shifted from the transition economies to Africa, which now receives almost a third of the total. This is part of the increased efforts of the international community to reduce poverty in low-income countries, including by helping countries improve governance through capacity building.

Developing and transition countries often lack enough skilled personnel to collect and analyze economic information, to formulate or carry out needed policies, including reforms, and to make the best use of foreign assistance. In fact, it is often such lack of capacity for policy design and implementation that hinders good policies, rather than lack of political will. The IMF has also found that such capacity is critical for ensuring full national ownership of reforms, which is a prerequisite for their effectiveness.

The term "capacity" can refer to both institutional capacity and human capacity. Poor institutional capacity (inadequate institutional structures and arrangements) or inadequate human capacity (lack of the needed skills among officials) can hamper the ability of government agencies to:

Where capacity is weak—where a government is unable to develop and successfully carry out its own policies—the consequences for society can be costly. For example, the inability of a government to make reasonably accurate budget projections will mean that it will be unable to make the best decisions on how to spend scarce public money. An inability to disburse funds as planned can also have serious consequences.

|

IMF Workshop on Banking Supervision |

Technical assistance is an important benefit of IMF membership that is generally free of charge. The exception relates to the assignment of long-term experts (defined as experts residing in a country for six months or more) for middle- and upper-income countries, which are asked to make a specified financial contribution to the IMF. (Currently, middle-income countries are expected to make a partial cash contribution and upper-income countries are expected to reimburse the full cost of long-term resident experts.) As a cooperative undertaking between the IMF and the recipient country, IMF technical assistance requires careful preparation and commitment of resources to succeed. Important in this regard are the assignment by the recipient authorities of counterpart staff and such complementary resources as office space and equipment, administrative support staff, communications facilities, material supplies, and utilities. These costs to the recipient government are over and above whatever charges may be levied by the IMF.

Although the IMF finances its technical assistance mainly from its own resources, member governments and other international organizations are important sources of additional financing. In the IMF's financial year ending April 2003, such external support—provided in the form of grants—financed a quarter of the IMF's total technical assistance (including training) activities. This type of cooperation not only increases the resources available for technical assistance, but also helps avoid duplication of effort. Bilateral donors include Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan (the largest donor), the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Multilateral donors include the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Union, the Inter-American Development Bank, United Nations agencies, and the World Bank.

The IMF delivers technical assistance in several ways. First, there is work done in the countries concerned. IMF staff can make short visits—usually of two to three weeks—to a country, or experts can be assigned to a country for periods ranging from a few weeks to several years. These missions and expert assignments provide countries with advice and hands-on support. Their scope can range from small missions responding at short notice to emergency requests, to large-scale, integrated, multiyear technical assistance programs cofinanced with other donors.

Second, from its headquarters in Washington, D.C., the IMF provides technical and diagnostic reports, training courses, seminars, workshops, and on-line advice and support through the Internet. At headquarters, the IMF's area departments—the African, Asia and Pacific, European I, European II, Middle Eastern, and Western Hemisphere Departments—which are responsible for country-level and regional surveillance, and lending operations—collaborate closely with the functional departments that provide the bulk of technical assistance—the Fiscal Affairs, Monetary and Financial Systems, Statistics, and Legal Departments, as well as the IMF Institute—in the planning, implementation, monitoring, and follow-up of technical assistance.

In recent years, the IMF has stepped up the regional delivery of some of its technical assistance, including training. It operates two regional technical assistance centers in the Pacific and the Caribbean, and also runs two centers in Africa. In the Pacific, the center has made significant contributions to the regional policy debate and agenda, and helped set up the Association of Financial Supervisors of Pacific Countries, for which it serves as the Secretariat. In addition to training offered at headquarters, the IMF Institute offers courses and seminars through a network of six regional training institutes and programs, established in collaboration with regional training partners (see page 49).

Collaboration with other technical assistance providers. The IMF cooperates with other providers of technical assistance such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the World Bank, regional development banks, the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), and other agencies. The high demand for, and costs of, technical assistance underscore the need to ensure that duplication and overlap are avoided, that help comes from the most appropriate source, and that operations are carefully coordinated. Collaboration with the World Bank has grown in areas where both institutions are active, such as strengthening financial sectors, fighting poverty in low-income countries, curbing money laundering, strengthening public sector management, and improving data collection and dissemination. The two institutions are also intensifying efforts to help countries mobilize their domestic resources and improve the quality of public expenditure.

To support trade liberalization through World Trade Organization negotiations, the IMF, with other international organizations, is helping low-income countries prepare for greater integration into the world trading system, both through diagnostic studies and on-the-spot assistance.

Measuring success. The success of technical assistance varies and depends on many factors, and many lessons are learned in the process of providing help. The IMF regularly evaluates the quality and results of its technical assistance.

An example of the regional approach to technical assistance is the Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Center (CARTAC)—a joint initiative of 20 Caribbean countries and 10 donor agencies—set up in November 2001. The center provides hands-on technical assistance and training to central banks, ministries of finance, tax and customs services, and national statistical agencies.

The main goal of the center is to help members improve their economic and financial management, particularly of budget and treasury operations and tax and customs administration; of domestic and offshore financial sector supervision and regulation; and of economic and financial statistics. The center coordinates its activities with other bilateral and multilateral agencies active in similar areas.

CARTAC delivers assistance through a team of resident experts, supplemented by short-term specialists, as well as through in-country workshops and seminars, training attachments, and regional training courses. Member countries and donors guide the center's work plan and operational strategy through a Steering Committee, which meets twice a year.

CARTAC's operations are implemented as a UNDP regional program, with the IMF serving as the executing agency. Within this framework, UNDP provides financial services support, while the IMF is responsible for managing the activities of the center, including the provision of the program coordinator and the recruitment and supervision of the resident experts. Canada has been a major force behind the creation of the center and finances more than 50 percent of its program activities. Other donors include Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Agencies involved in the financing of the center include the Inter-American Development Bank, the Caribbean Development Bank, and the World Bank.

CARTAC's activities have included:

In Cambodia, technical assistance during 2001–03 was coordinated through a Technical Cooperation Action Plan (TCAP) and implemented as a joint IMF-UNDP technical assistance project, cofinanced by Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the Asian Development Bank.

Donors wanted to assist the government in strengthening its overall capacity to formulate and carry out sound economic policies that promoted growth, stability, and poverty reduction, with an emphasis on better management of public finances. Through advisory services, training, and introduction of automation and management information systems, the project was designed to strengthen the institutional capacities of key departments in the Ministry of Economy and Finance—the Treasury, the tax, customs and excise, and the budget departments—as well as the National Bank of Cambodia and the National Institute of Statistics. The project also promoted linkages between macroeconomic policies and poverty reduction. Improved capacities in these areas enable the government to better monitor and accomplish its poverty reduction strategy.

The Action Plan had four main components:

Four additional components were financed and carried out directly by other participating agencies: a public finance management component financed and implemented by the Asian Development Bank; a health sector public expenditure management component financed by the Netherlands and implemented by the World Health Organization; a governance studies program financed and implemented by the United Kingdom's Department for International Development; and a policy study and research component on how to help the poor more effectively, financed and implemented by the UNDP.

A number of recent initiatives have boosted demand for IMF technical assistance. These include a joint program with the World Bank to assess and help strengthen the financial sectors of member countries, and programs to encourage the adoption of international standards and codes related to the government, financial, and corporate sectors (see page 27); to track public spending and other measures for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative; and to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism (see page 30). Against this background, the IMF's Executive Board has stressed linking IMF technical assistance to the institution's priorities; focusing it more sharply on the core areas of the IMF's responsibilities and expertise; improving the delivery of technical assistance; and mobilizing more outside funding. In addition, countries requesting technical assistance must be fully committed, both at the political level and within the institutions involved, not only to supporting the IMF's assistance effort, but also to making use of the assistance received.

Because of competing demands for its technical assistance resources, the IMF has put in place a formal framework for selecting projects, which uses a set of "filters" to assess requests and to help in allocation decisions. The first category of filters divides requests into seven main program areas or key policy initiatives covering crisis prevention, poverty reduction, crisis management and resolution, post-conflict/post-isolation cases, regional/multilateral arrangements, promotion of international standards and codes, and financial sector assessment programs. These program areas are complemented by three further categories of filters, as follows:

To ensure that the IMF's technical assistance is effective and brings lasting benefits, it is planned and carried out with the full involvement of the authorities of the recipient country at each stage of the process—from the identification of needs, through discussion and agreement on terms of reference and project goals, to implementation and then monitoring progress. The degree of country ownership has a direct bearing on the effectiveness of the technical assistance.

China is a good example of a technical assistance program that has benefited from strong country ownership. Since the 1980s, the government has introduced sweeping economic reforms, and the IMF has played a substantial role in helping China design and implement them. The reform program has entailed far-reaching legal and other changes that have created a need for officials to be trained in a variety of fields. The major government agencies—the People's Bank of China, the State Administration of Taxation, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Statistical Bureau—have all been recipients of IMF technical assistance.

Technical assistance contributed to the creation of a two-tier banking system; the development of indirect monetary controls; the rationalization of the foreign exchange market; the reform of the fiscal system (for example, improvement of the tax administration, reform of the tax system, introduction of the budget law, and strengthening of public expenditure management); the improvement of economic and financial statistics; and the training of officials.

In particular, the IMF has provided extensive technical assistance related to the financial sector and financial markets, in the form of training workshops and seminars on banking regulation, capital account liberalization, and foreign exchange market infrastructure. Efforts to speed up China's movement toward international best practices in banking supervision and prudential regulation are being supported by regular visits by a banking supervision expert from the IMF's Monetary and Financial Systems Department.

The IMF has also collaborated closely, particularly with the State Administration of Taxation, on a number of tax reform projects. The aim has been to modernize tax administration partly by adapting the international policies and practices best suited to the unique characteristics of China's economy. The IMF has advised on tax laws, held seminars and workshops, and arranged study tours abroad for Chinese officials. Improvements in the overall legal framework of the tax system have also been supported by IMF technical assistance, including training.

In 2000, the IMF and the People's Bank of China established the Joint China-IMF Training Program to train officials involved in devising and implementing macroeconomic and financial policies and in compiling and analyzing statistics. The program includes several training events each year.

Technical assistance can improve lives in a variety of ways. In the next few pages we take a look at examples of how the IMF has helped governments build institutional capacity in Africa; meet internationally recognized standards for collecting and publishing financial data; combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism; and strengthen taxation systems and financial sectors. We also discuss how the IMF helps countries after an emergency or conflict; and the role of the IMF Institute in training government officials.

The IMF launched its Africa Capacity-Building Initiative in 2002. It is part of the IMF's response to the urgent call by African leaders—including under the New Partnership for Africa's Development—to strengthen economic governance and the capacity of governments to carry out sound economic policies that contribute to reducing poverty.

As part of the Initiative, the IMF decided to establish several African Regional Technical Assistance Centers—known as AFRITACs—in sub-Saharan Africa. The AFRITAC idea is modeled on the existing Caribbean and Pacific centers, which have shown that a decentralized, regional approach to identifying and meeting technical assistance needs makes it easier for country authorities to have a voice in setting priorities. And that, in turn, both enhances country ownership and commitment and encourages an efficient use of technical assistance resources. Placing such resources directly in the region has the added advantages of increasing IMF staff's familiarity with the needs of the countries and allowing a more flexible and rapid response to capacity-building requirements. The AFRITAC initiative builds on efforts already under way in Africa, notably the Partnership for Capacity Building in Africa and its implementing agency, the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), in which the IMF participates.

The IMF opened its first AFRITAC—the East AFRITAC—in Dar es Salaam in late 2002. The member countries of the East AFRITAC are Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. The East AFRITAC is staffed by a center coordinator and five resident experts. Their work is supplemented by short-term specialists. The Tanzanian government provides office space and logistical support for the Center.

Priorities for the Center in Dar es Salaam include:

Developing the Initiative, IMF Management decided, with the cooperation of the Malian government, to set up the West AFRITAC temporarily in Bamako in May 2003. This Center operates on the same model as the East AFRITAC and serves 10 countries in West Africa.

To enhance the technical assistance provided by the AFRITACs, the ACBF, in partnership with the IMF, will develop training programs responsive to the particular needs of the African countries concerned.

An important part of the IMF's technical assistance work is helping countries meet internationally recognized standards in a variety of areas relating to economic policymaking. The international community has attached increasing importance to the dissemination and implementation of standards and codes, particularly as a means of strengthening crisis prevention. The idea is that providing benchmarks of good practice, encouraging their implementation, and measuring progress against them will improve the quality of policymaking and investment decisions. The IMF and the World Bank have played leading roles in these efforts. They act as standard setters in their respective areas of expertise, assess member countries' observance of standards and codes, and help them make reforms where needed.

The work on standards and codes falls into three broad groups, covering the government, the financial, and the corporate sectors. Within those groups, the IMF and the World Bank have recognized 12 areas and associated standards as useful for their operational work. They comprise data; monetary and financial policy transparency; fiscal transparency; banking supervision; securities; insurance; payment systems; corporate governance; accounting; auditing; insolvency and creditor rights; and anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism. Beyond their areas of responsibility, the IMF and the World Bank also cooperate with other standard-setting bodies in each of the 12 areas.

Statistics. The IMF's technical assistance to promote international best practices in statistics focuses on capacity building and improving data quality. It is offered in the areas of balance of payments, government finance, monetary and financial, and national accounts and price statistics. In all these areas, technical assistance is designed to improve the coverage, collection, compilation, accuracy, reliability, timeliness, and dissemination of official statistics. In addition to providing assessments of all these dimensions of statistical quality, technical assistance missions also often deliver on-the-job training, assist in designing reporting forms and spreadsheets to aid correct classification, and lay out short- and medium-term action plans for the improvement of statistical procedures.

Advisors may make frequent visits to countries to help them improve statistical quality. An alternative is the placement of long-term statistical advisors in countries most needing assistance. The latter approach has proven particularly effective in Africa, and in the transition countries, where there was an urgent need to build a statistical infrastructure that would buttress the move to market-oriented economic systems. In recent years, statistical advisors have served in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), Timor Leste, Ukraine, and at the Caribbean, East African, and Pacific technical assistance centers. National accounts experts have also been active in Kuwait, Mongolia, and Uganda.

Strengthening financial systems. The IMF provides a considerable amount of technical assistance in support of the joint IMF-World Bank program to strengthen financial sectors, the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP). Resilient, well-regulated financial systems are essential for macroeconomic and financial stability, especially in a world of large-scale capital flows. Supported by experts from a range of national agencies and standard-setting bodies, work under the program seeks to identify the strengths and vulnerabilities of a country's financial system; to determine how key sources of risk are being managed; to ascertain the sector's developmental and technical assistance needs; and to help prioritize policy responses. Detailed assessments of observance of relevant financial sector standards and codes, which give rise to Reports on Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSCs) as a by-product, are a key component of the program. Follow-up technical assistance is normally provided to help countries meet these codes.

Following the events of September 11, 2001, the IMF has expanded its technical assistance on anti-money laundering to include measures to combat the financing of terrorism. While the IMF is not a law enforcement agency, it is contributing to the global efforts to crack down on these two problems.

IMF technical assistance has helped countries that have requested assistance to bolster their financial systems and improve controls to prevent abuse by criminals. A major role of the IMF is to assess the legislation, institutions, and controls that are in place outside criminal law enforcement to see what improvements could be made to close potential loopholes. Technical assistance in this area can promote good governance and integrity in financial markets, and is an integral part of the IMF's efforts to help countries strengthen financial sector regulation and supervision, and reduce the incidence of financial crime.

The IMF and the World Bank have endorsed standards designed to curb money laundering and the financing of terrorism, based on the recommendations of an international task force, and have developed—in collaboration with other international bodies, including the United Nations—an agreed way for reviewing compliance. A pilot program of assessments was initiated in October 2002. The results of these assessments provide the IMF and other bodies with a sound basis for identifying technical assistance needs at the national and regional levels. As part of this work, the IMF is assisting in the following broad areas:

The IMF and World Bank have set up a joint database to help make best use of the scarce resources used to back this coordinated international effort. The database allows the regional bodies dedicated to combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism to enter technical assistance requests on behalf of their member countries and provides the donor community with a mechanism to learn about and respond to such requests swiftly. The coordination database became operational in December 2002.

Box 2 The initiatives taken by the Central African Economic and Monetary Union (CEMAC) are an interesting example of the global campaign to stop money laundering and the financing of terrorism. The IMF has been helping the leaders of this franc currency zone to introduce legislation and strengthen the institutions needed for combating financial crime. Africa's increasing integration into the world economy, especially the franc zone, has meant greater capital mobility and the rapid development of modern payment methods associated with new information technologies. These developments have provided increasingly sophisticated tools for laundering the proceeds of crime while preserving the anonymity of transactions. CEMAC leaders have created a task force to help coordinate action and introduce legislation and regulations across the community to support the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism. In early 2003, the IMF assigned an expert to the Bank of the Central African States to train officials and assist with putting in place relevant regulations. |

The IMF's technical assistance includes helping member countries promote sound and efficient banking and financial systems, and implement effective monetary and exchange rate policies. Essential to these ends is a strong central bank. An interesting example of technical assistance to a central bank linked to a change in an exchange rate arrangement is provided by Lithuania.

Following the introduction of its national currency, the litas, in 1994, Lithuania decided to operate a currency board regime—a strictly fixed exchange rate system—linked to the U.S. dollar. After several years of operation, the currency board was credited with supporting economic stability, but the peg to the dollar increasingly threatened to undermine the country's emerging trade and economic integration with the European Union (EU). Lithuania being a candidate for membership in the EU, the authorities—supported by the IMF—decided to switch the peg for the litas from the dollar to the euro, while maintaining the currency board arrangement.

In March 2001 a technical assistance mission from the IMF's Monetary and Financial Systems Department visited Vilnius to help the authorities formulate a program to "repeg" the Lithuanian currency. The mission designed a comprehensive plan, including legal steps needed for the switch, adjustments in central bank operations, a time frame and supporting measures for the adjustment of private sector contracts, and a plan for reorienting the country's foreign exchange reserves policy. Given the unprecedented nature of this process—no modern currency board had previously attempted to "repeg" to a different currency—and the importance of reassuring the public about the safety of the plan, the mission also discussed public information strategies.

The authorities followed the mission's recommended plan of action, which covered the whole period from the mission's visit to the day of repegging. In the event, the switch—implemented on February 1, 2002—proceeded smoothly, with public support and no adverse market reaction. Lithuania's currency is now pegged to the euro—the currency of its major trading partner—and floats with it against the dollar.

Box 3 Poland was among the first centrally planned economies to adopt market-oriented reforms, and IMF technical assistance played a significant role in the successful modernization of the National Bank of Poland (NBP), which served as a catalytic force in the overall financial sector reform in the course of the transition. The approach was innovative and dynamic, focused on delivering a comprehensive technical assistance program covering all operational areas of the NBP, while introducing regulatory procedures to improve existing structures. The case was a good example of effective coordination of technical assistance from different sources, including the IMF, the World Bank, the European Union, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Central banks from Austria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States contributed experts to help with different aspects of the modernization program. These included banking supervision, monetary management and development of the money market, the setting up of research and analysis teams, central bank accounting and internal auditing, foreign exchange operations, and the modernization of the interbank payments system. The IMF coordinated the work of these experts in their different fields, managing an extensive program of assistance, and ensuring its overall consistency and relevance. |

No one likes to pay taxes. But without them governments could not deliver essential services. Given that taxes are necessary, governments should aim to ensure that tax systems are broad based, fair, efficient, and simple to administer. Such tax regimes promote revenue collection, while reducing opportunities for evasion. To help governments achieve these aims, the IMF advises countries on the design of tax policy and provides technical assistance to strengthen tax and customs administration. As a result, the revenue-raising capacity of governments in many countries has increased, which in turn has allowed more spending on important services.

IMF advice on tax systems and policy has helped countries around the world—from Russia and China to many countries in Latin America (including recently Argentina, Brazil, Honduras, and Peru) and Africa—to improve tax codes and reform tax structures to make them better suited to a modern economy. For example, IMF experts have helped many countries introduce a value-added tax (VAT), which tax specialists regard as an efficient way of taxing economic activities.

The staffs of the IMF, OECD, and World Bank are also working together to establish an "International Tax Dialogue." Its main purposes—to facilitate technical discussions and experience sharing among government officials responsible for tax administration and policy, and to improve coordination among technical assistance providers—will benefit developing and developed countries alike.

IMF technical assistance on harmonizing tariffs and taxes among the eight countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU)—Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo—was launched in 1997. The assistance, which is continuing, has been delivered in a variety of ways, including missions and the assignment of experts to both member countries and the WAEMU commission, and the participation of officials in training activities.

Technical assistance to WAEMU has covered the implementation of a common external tariff, the harmonization of indirect taxes and of withholding taxes to strengthen the taxation of the informal sector, and the introduction of a common transparency code for public finance management. Major objectives have been to help member countries evaluate the potential revenue impact of adopting the external tariff and identify compensatory measures while further improving the efficiency of tax and customs administrations; and to advise the WAEMU commission on a strategy to harmonize indirect domestic taxation based on best international practices.

Regulations for VAT and the harmonization of excises were issued in December 1998; all tariff barriers among member countries were eliminated in January 2000; a common external tariff was introduced on the same date; and common legislation for petroleum taxation and withholding schemes was adopted in November 2001. Close coordination between the IMF and the World Bank, the European Commission, and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (General Directorate of Development) was critical in developing this vision and strategy.

Improving tax yields was the main objective in Guatemala, where IMF technical assistance helped reform the tax system and its administration. A technical assistance mission, consisting of IMF experts in tax policy and administration, visited Guatemala in 1997. The team worked closely with officials from the Ministry of Finance, the tax administration, and representatives of the business and taxpayer communities to design a strategy to reform the tax system and its administration. Subsequently, the proposed reform strategy was implemented with the support of a technical assistance loan from the World Bank, which financed the assignment of a number of technical experts. These experts helped the Guatemalan authorities carry out specific aspects of the action plan. Close coordination between the IMF and the World Bank ensured that the project's execution was consistent with the reform strategy. This type of coordination is now being pursued in a systematic way throughout the region, including in Bolivia and Colombia.

The strategy's main goal was to design a set of tax policy and administration measures that would raise the tax revenue-to-GDP ratio to about 12 percent of GDP from the historically low level of about 8 percent, and rationalize and simplify the tax system to enhance its efficiency. The achievement of the 12 percent tax ratio was an important goal established under the 1996 UN-sponsored Peace Accords because it would permit higher social spending in a sound fiscal framework.

Initial progress was slow. Nonetheless, a key element of IMF advice on strengthening tax administration was implemented through the creation of the Tax Administration Agency in 1999, which incorporated the existing internal tax and customs revenue agencies. With new legislation improving procedures, tax evasion became effectively punishable under the law.

In July 2001, the Guatemalan legislature approved a tax reform that included an increase in the VAT rate from 10 percent to 12 percent, a doubling of the presumptive income tax rates, and a broadening of the tax base through the elimination of several exemptions. Tax administration is also being enhanced through the creation of a special unit for large tax payers, more frequent and in-depth tax audits, and sanctions for noncompliance. These measures helped raise tax revenue (to close to 11 percent of GDP in 2002), enabling the government to reduce the fiscal deficit while safeguarding social expenditures.

|

In several countries—such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Ethiopia, and Indonesia—the IMF has helped with government plans for fiscal decentralization, including both revenue collection and spending. IMF teams have focused on helping authorities design efficient systems of fiscal relations between the central and subnational governments. Issues have included the assignment of revenue and spending responsibilities at each level of government, the design of an effective system of grants from the center to the subnational level, the introduction of specific safeguards to allow local government borrowing without endangering macroeconomic stability, and the identification of administrative and technical requirements in budget reporting and budget preparation for subnational governments. |

Integration into the world economy is an essential part of any strategy to raise living standards in low-income countries, but many of these countries need help in assessing the effects of lowering trade barriers and drawing up strategies to cope with problems.

To provide such help for the least-developed countries (LDCs) (as classified by the UN), the Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance was established in October 1997, by a High-Level WTO Meeting. The framework aims to enhance the efficiency of trade-related technical assistance to the LDCs, including by improving coordination among donor agencies and by making trade policy part of LDCs' poverty reduction strategies.

The framework is a cooperative effort among the IMF, UNCTAD, the UNDP, the WTO, and the World Bank, along with donor countries and the 49 countries being helped.

Under the framework, diagnostic trade integration studies—which review the trade environment and identify priority policy, technical assistance, and project needs—are used to integrate trade into countries' poverty reduction strategies. The IMF's inputs for these studies relate mainly to macroeconomic and competitiveness issues and to the external economic environment. As of March 2003, seven diagnostic studies had been completed; as many LDCs as feasible will be covered before the conclusion of the Doha round of WTO trade negotiations.1

The IMF's support of the framework includes follow-up technical assistance in its areas of expertise. For example, in Cambodia, the IMF has stationed a long-term expert on customs modernization and undertaken mission work on customs and tariff reform.

Technical assistance from the IMF has played a major role in helping the Baltic countries, Russia, and other countries of the former Soviet Union set up treasury operations to manage financial resources effectively. In most advanced economies, treasury systems, operated by the ministry of finance and using a network computer system, handle payment processing, accounting, reporting, and financial management services for the finance ministry, spending ministries, and spending units. Such systems may also include further modules for budget preparation, debt management, extrabudgetary fund management, and local government finances.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, such systems did not exist in its constituent countries. The new governments struggled to shift from a command to a market economy without the necessary institutions to run their budgets. In virtually all of the 15 countries of the former Soviet Union, IMF experts helped the governments set up from scratch new treasury systems that were critical for controlling public finances.

The extent of the IMF's involvement varied from country to country. In most cases technical assistance from the IMF had three elements—first, helping the national government develop an appropriate treasury concept for the economy; second, fine-tuning the concept into a country-specific model; and, third, assisting in the implementation of the systems. Each element was a major undertaking, fraught with problems and technical difficulties—not all dealt with successfully.

By the end of 2001, while much remained to be done, the basic goal of building treasury systems in the 15 countries had largely been met.

A good example of the process can be seen in Kazakhstan. Technical assistance was provided to Kazakhstan to improve budget management, including revenue and expenditure classification in accordance with international standards, commitment controls, a treasury single-account-and-ledger system, and the inclusion of extrabudgetary funds and off-budget accounts within the budget. IMF technical assistance to Kazakhstan began in 1994 and is continuing; it has been delivered by a resident advisor and through visits by a large number of IMF and other experts. Achievements have included a clear and transparent legal framework for the budget; clear institutional responsibilities and close collaboration across budget institutions; a chart of accounts that incorporates the budget classification; and the avoidance of significant extrabudgetary and off-budget activities. There are many reasons for this success, including a strong commitment to reform, a proactive use of IMF assistance, an emphasis on building strong stakeholder support, effective coordination among various technical assistance providers, and realistic time frames. The progress of Kazakhstan's budget reform has extended beyond its frontiers, and other countries, such as Mongolia, are adopting similar reforms based on the "Kazakh model."

In Mongolia, the IMF gave advice to the government on how to introduce a treasury single-account system at the Bank of Mongolia, the country's central bank, to strengthen public expenditure management. Janis Platais, an IMF Budget and Treasury Advisor, writes about some of the difficulties he encountered in implementing the advice.

In 2000, Mongolia's expenditure management system was suffering from lax financial discipline and a lack of timely and reliable data on different aspects of budget management. Government balances were scattered all over the banking system. Introducing a treasury single account was a key component of a concessional loan program approved by the IMF's Executive Board in September 2001. But the small number of staff members in the accounting section of the Ministry of Finance and Economy and their need for training in up-to-date concepts of financial management required external assistance.

I traveled to Ulaanbaatar to help the government address the weaknesses in the public expenditure management system by establishing an efficient treasury single-account arrangement. Upon arrival, I faced a number of difficulties.

Working together, we overcame these difficulties. Drawing on lessons learned from other transition economies operating in similar circumstances, the Ministry of Finance and Economy secured the cabinet support needed to finalize the conceptual design of the new treasury arrangement.

To complete the arrangement on schedule, the ministry quickly hired additional staff, reorganized the structure of local governments to accommodate the new treasury service, and trained concerned staff. I helped draft treasury regulations, conducted numerous training sessions, and helped the ministry evaluate progress at the local government level.

The ministry and the governors of local governmentsfound that the new

arrangement provided a better way to implement their budgets, preventing

budget units from running into the red and supplying much better information

on the budgetary position of the various local governments.

|

IMF Treasury advisor Janis Platais (center) demonstrates the use of the single-account network at a local government office in Mongolia. Japanese officials (left) and local staff look on. |

When the IMF steps in to help meet the special needs of a country after an emergency or conflict, it does so as part of a concerted international effort, with different agencies and donors taking the lead roles in their respective fields of responsibility and expertise. The IMF's primary role in post-conflict countries is to help reestablish economic stability as an essential foundation for sustainable growth. Initially, this is done through technical assistance and policy advice to help rebuild the administrative and institutional capacity of the country. Once the situation has stabilized sufficiently, the IMF can make financial assistance available, which in turn usually triggers support from other creditors and donors.

|

An IMF team meets with a senior tax official and his staff in Kabul in 2002. |

In the aftermath of two recent conflicts, in Kosovo and Timor Leste, the United Nations asked the IMF to provide immediate technical assistance to help establish rudimentary central banking and finance ministry operations. In both cases, the IMF's Monetary and Financial Systems Department undertook to set up banking and payment services, and to develop the basic institutional structure for a modern, market-based banking sector. The Fiscal Affairs Department advised on how to establish essential fiscal institutions virtually from scratch.

In Kosovo, IMF advisors prepared four basic draft laws (on the use of currencies, banking, the establishment of the Banking and Payments Authority of Kosovo, and payment transactions). The first three of these were adopted in late 1999. The IMF provided an expert to serve as the Managing Director of the Payments Authority. A number of additional short-term monetary and banking experts also contributed to the development of the Authority, which officially opened on May 19, 2000. Since then, it has licensed several commercial banks and has provided payment services in euros. Following the passage of enabling legislation, the central fiscal authority was established as a nascent Ministry of Finance. The IMF's Fiscal Affairs Department coordinated this effort with the World Bank, the EU, and bilateral donors, orchestrating assistance from different sources and guiding the work of the experts provided.

In Timor Leste, IMF staff assisted with the preparation of key financial legislation designed to restart the fledgling economy following its turbulent split with Indonesia in 1999. Regulations to establish a Central Payments Office, to designate the U.S. dollar as the legal tender, to license currency exchange bureaus, and to oversee the banking system were approved by the UN Transitional Authority for East Timor in early 2000. IMF staff also helped establish a Central Fiscal Authority responsible for developing and managing the budget as well as revenue policy and its administration. Part of the challenge was building up the skills of the local administration and finding the right personnel to run the newly created government agencies. The IMF also assigned long-term resident advisors to the monetary and fiscal authorities with financial support from the United Nations, Japan, and Portugal. A residential statistical advisor assisted with the passage of a statistics law, establishing a national Statistics Agency, and with the collection, compilation, and dissemination of data on poverty, national accounts, prices, and the balance of payments.

|

Åke Lönnberg from the IMF (right) shows samples of U.S. dollars and coins to central bank and postal staff in Timor Leste after the dollar was declared legal tender.I |

Scott Brown was the IMF's mission chief for Bosnia and Herzegovina during 1995–98, and returned to the region in 1999 on a technical assistance assignment with the United Nations Interim Administration in Kosovo. He is currently an Advisor at IMF headquarters. He writes about some of the difficulties of working in an area ravaged by war.

|

Scott Brown, the IMF's mission chief for Bosnia and Herzegovina during 1995–98. In 1999 he returned to the region on a technical assistance assignment with the United Nations Interim Administration in Kosovo. |

We began work in Bosnia and Herzegovina in October 1995, after the cease-fire entered into effect, but before the start of the Dayton peace conference. The early IMF missions flew to Sarajevo in military cargo planes chartered by the United Nations; the UN also arranged convoys to other cities in Bosnia. Except for the evening when a mission hotel came under mortar fire, the working atmosphere was good; knowing how their counterparts had to live, staff showed humor and tact in coping with unreliable electricity, communications, heating, and water, and long periods standing around in the frozen mud. The initial focus was on preparing Bosnia and Herzegovina for membership in the IMF, paving the way for reconstruction assistance, in close cooperation with the World Bank. Next was the urgent task of restarting economic activity without losing control over financial balances. This was complicated by physical destruction and supply bottlenecks, a weak and fragmented administration, and deep-rooted structural problems inherited from the previous system. With strong efforts on both sides, Bosnia and Herzegovina became a member of the IMF on December 20, 1995; at the same time, it became the first country to receive financing under the IMF's facility for emergency post-conflict assistance.

The IMF had a key role in setting up postwar economic institutions and was responsible for appointing the expatriate governor of Bosnia's new central bank. This work was, to put it mildly, complicated by the highly decentralized system of government envisaged in the Dayton/Paris peace treaties and the requirement that important decisions be reached by consensus among three formerly warring groups. Working persistently throughout the country, IMF staff helped create a federation-wide fiscal and financial system in 1996; the initial state institutions, including the Central Bank, in 1997; and the full integration of the Republic of Serbia, the successful introduction of Bosnia's new currency, and Bosnia's first IMF Stand-By Arrangement in 1998.

In June 1999, the IMF faced a new challenge in planning for technical assistance to postwar Kosovo. It soon became clear that there was a missing link: local counterparts. Most public officials had fled the province and, while the UN had been given the job of administering Kosovo, it needed help to get up to speed quickly.

I worked with the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) during its start-up phase through late December 1999. My department in UNMIK was responsible for starting up the financial sector; organizing the Economic Policy Advisory Group of local economists and business people; drafting UNMIK regulations (in effect, laws); and acting as a counterpart to missions from the international community, including the IMF.

Starting almost anew, UNMIK and our partners did whatever we had to do. The idea, for example, of "establishing a customs administration and payments system" gained new meaning during the six-week period during which I took physical possession of the new keys and combinations to vaults of the former payments system, began carrying customs receipts from the border under military convoy, and made bulk deliveries of currency to UN staff for payment of local salaries and social assistance. By the time I left Kosovo, the province had a working budget, treasury, and a Banking and Payments Agency, and was preparing to license its first private commercial bank.

The IMF Institute trains officials from member countries through courses and seminars focused on four core areas—macroeconomic management, and financial sector, fiscal, and external sector policies. These are delivered by Institute staff or by staff from other IMF departments, occasionally assisted by academics and other experts. Training is delivered at IMF headquarters in Washington, D.C., and at various overseas locations, with officials from developing and transition countries being given some preference in acceptance for courses.

Over the past few years, building on the favorable experience with the Joint Vienna Institute (see next page), the IMF Institute has developed a network of six regional training institutes and programs, located in Austria, Brazil, China, Côte d'Ivoire,2 Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates. Setting up this network has allowed the IMF Institute to expand training considerably, leveraging its own resources with contributions from regional training partners in the form of teaching facilities, administrative resources, and co-financing of participant costs.

New technology applications have contributed to the expansion of training through a distance-learning course on Financial Programming and Policies, delivered for the first time in 2000. This course, available three times a year, combines 910 weeks of Internet-based instruction with a two-week residential segment in Washington, D.C., and is particularly helpful for officials who are unable to leave their jobs for a long period.

Courses and seminars in Washington remain a central part of the IMF Institute's program. Headquarters-based courses offer access to a broader range of staff experience and skills than can be marshaled for overseas activities, which is especially important for longer courses. Washington participants, coming from all regions of the world, can more broadly compare experiences and develop a wider network of contacts. They can also more easily gain insights into the operations of the IMF and have the chance to meet with a range of IMF staff.

The IMF Institute keeps its curriculum well attuned to the training needs of countries through a number of channels. First, the increased role of the regional institutes and programs enables the Institute to adapt the mix of courses and course materials to regional needs. Second, the IMF Institute develops new courses in response to emerging issues. Over the past few years, it has put particular emphasis on helping countries to prevent and manage financial market crises. Third, the IMF Institute tailors short seminars on key current issues to the needs of high-level officials. Recent seminars have covered exchange rate regimes, fiscal rules, globalization, investor relations, inflation targeting, and poverty reduction. Finally, the active research program maintained by the IMF Institute's staff helps ensure that its programs are topical and state-of-the-art. The research is published by the IMF, along with training materials and case studies.

Box 5 The Joint Vienna Institute (JVI) was established in 1992 as a temporary training center for officials from the transition countries of eastern and central Europe, Asia, and the former Soviet Union. The original sponsoring organizations of the JVI were the Bank for International Settlements, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the IMF, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the World Bank. The World Trade Organization became the sixth sponsoring organization in 1998. In 2002, the Institute's six sponsoring organizations and the Austrian authorities agreed to make the JVI a permanent training institute, financed jointly by the IMF and the Austrian authorities, as primary sponsors, supplemented by contributions from the other organizations and bilateral donors. In May 2003, the JVI moved to a new facility provided by the Austrian authorities. The Joint Vienna Institute offers practical training that reflects the diverse expertise of its sponsoring organizations. Lecturers at the JVI are staff members from the JVI's sponsoring organizations, who bring their hands-on experience into the classrooms. While the subjects taught at the JVI include a range of standard topics such as macroeconomic analysis and policy, and monetary and financial statistics, seminar topics are revised each year, with new courses added and others dropped in line with the changing needs of the participant countries. Subjects offered include, for example, advanced external sector issues, consolidated supervision of banks, design and implementation of new migration polices, financial transactions for lawyers, promoting financial stability, and tax policy and administration. The JVI trains about 1,500 officials a year, with the IMF responsible for about half of the total training. Participants come from more than 30 countries and all seminars include representatives from a mix of countries. This results in lively exchanges and enhances training through a sharing of experience. In addition, participants acquire professional contacts in other transition countries with whom they can network. |