High Uncertainty and the Unknown

Despite the global economy’s postpandemic resilience, economic disruption is likely from a myriad of transformative forces, such as climate change, geopolitical fragmentation, conflict, digitalization—combined with cyber risks— and artificial intelligence (AI). The immediate future promises to be one of continued high uncertainty.

One source of that uncertainty is the effect of climate change, which presents a major threat to countries’ long-term growth and prosperity. Global ambitions and policy implementation gaps persist. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions to keep the increase in the global average temperature well below 2°C above preindustrial levels—and ideally to 1.5°C— calls for urgent action.

Uncertainty arises as well from predictions of the weakest medium-term global growth in three decades (see “Spotlight 1: Sustaining the Recovery”). A significant and broad-based slowdown in total factor productivity growth accounts for more than half of the decline. Exacerbating the slowdown is a widespread drop in post crisis private capital formation and slower working-age population growth in major economies. Without timely policy interventions or a boost from emerging technologies, global growth is expected to be only 3.1 percent by the end of the decade, significantly below its prepandemic (2000–19) average by 1 percentage point. Improved capital and labor allocation to more productive firms will be essential to enhance growth.

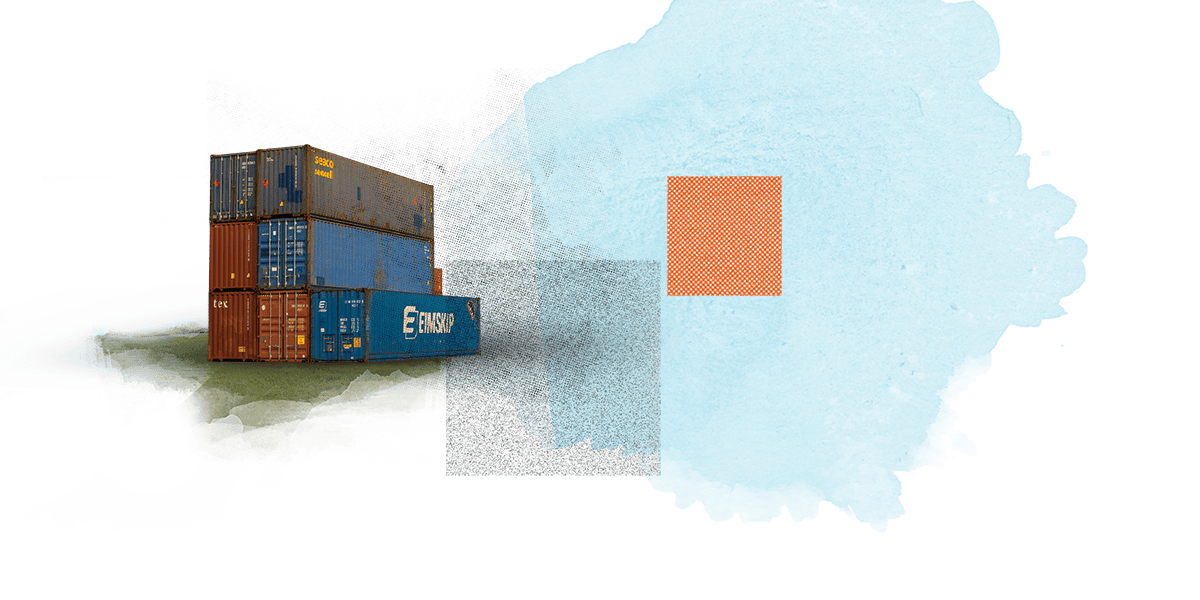

The view that the world is transitioning to a low-growth economy has been fueled in part by increasing geopolitical fragmentation—a world where geopolitics determines trade and investment decisions and, at its extreme, triggers the creation of rival economic blocs. Reversals in trade, capital flows, and investment are already reshaping the global economy. Nearly 3,000 trade-restricting measures were imposed in 2023, almost three times the number during 2019. This trend risks reversing the transformative gains from past global economic integration. Restrictions diminish efficiency gains from specialization, limit economies of scale, and reduce competition. Greater integration of the global marketplace and more complex value chains mean the cost of fragmentation will be higher.

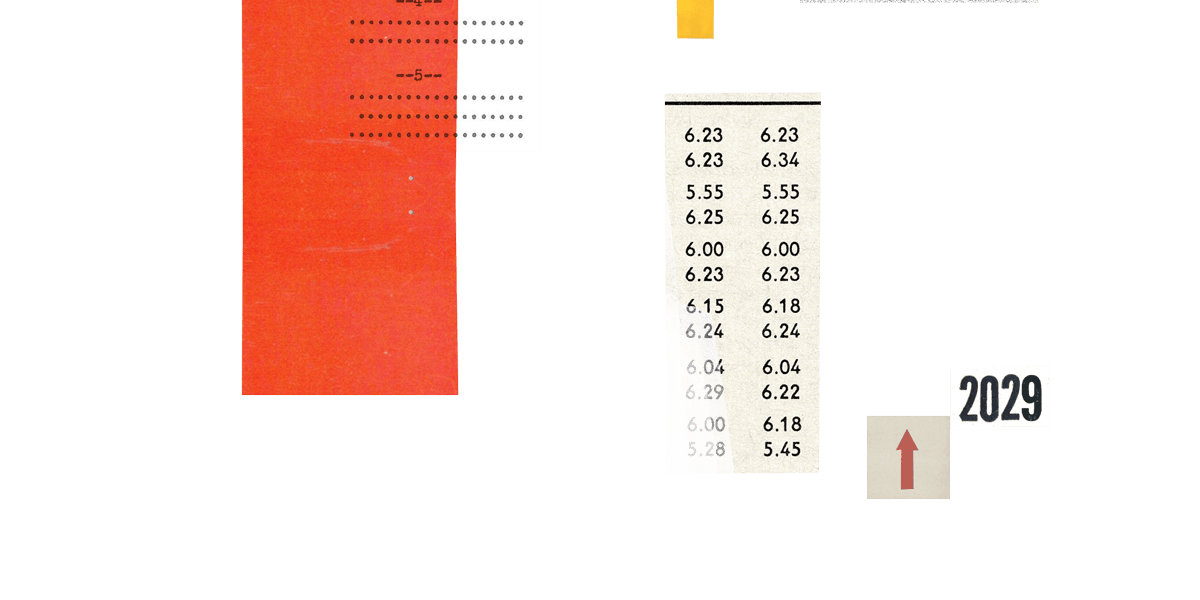

Figure 1.3

Geopolitical Fragmentation Is Affecting Trade

(Percentage point differences in trade growth before and after the start of war in Ukraine)*

Sources: Trade Data Monitor; and IMF staff calculations.

Notes: *Bilateral quarterly growth rates are computed as the difference in log bilateral trade averaged using weights equal to the bilateral nominal trade. Strategic sectors include the following Harmonized System two-digit chapters: 28, 29, 30. 38, 84, 85, 87, 88, 90, 93. Before war is between 2017:01 and 2021:04.

** The bloc definition is based on a hypothetical bloc comprising Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the US and a hypothetical bloc including China, Russia, and countries siding with Russia during the March 2, 2022, UN General Assembly vote on the war in Ukraine. Other countries are considered nonaligned.

Greater geoeconomic fragmentation has also put governments under increasing pressure to adopt more active industrial policy stances. In some cases, these industrial policy measures can help address market failures. But they can also prove costly and lead to various failures, ranging from corruption to misallocation of resources. Industrial policies can also lead to damaging cross-border spillovers, raising the risk of retaliation by other countries, which can ultimately weaken the multilateral trading system and worsen geoeconomic fragmentation.

Conflicts are a major driver of economic fragmentation, and greater political instability and conflict have been a hallmark of the reporting period. The wars in Ukraine and in Gaza are two prominent examples of the many conflicts disrupting global recovery and growth. Over the past decade, for example, parts of Africa and the Middle East have faced conflict, civil unrest, and food insecurity. IMF analysis suggests that this may cause an economic contraction of up to 20 percent in the Sahel. If the situation persists, more than 60 percent of the world’s poor will live in fragile and conflict-affected states by 2030.

Growing economic fragility and the conflict landscape do not portend well for the global economy; in contrast, other forces, such as digitalization could prove to be a boon. But these forces will also require thoughtful responses to mitigate the dislocation they might trigger.

The comprehensive integration of digital technologies into all aspects of economic and financial systems, processes, and policies has the potential to reshape the international monetary system. Some governments have been slow to harness digital technology to improve the delivery of public services and strengthen public finance. To maximize gains from digitalization, policymakers will need to link unconnected households to the internet and facilitate the adoption of digital solutions in the public sector.

Greater digitalization, combined with heightened geopolitical tensions, involves its own risks—for example, in the form of cyberattacks. The potential for systemic consequences has risen alongside the danger of extreme losses from cyber incidents. Such losses could potentially cause funding problems for companies and even jeopardize their solvency. Policies and governance frameworks at firms must keep pace with these rising dangers. The IMF actively helps member countries strengthen their cybersecurity frameworks through policy advice, including as part of the Financial Sector Assessment Program, and through capacity-building activities.

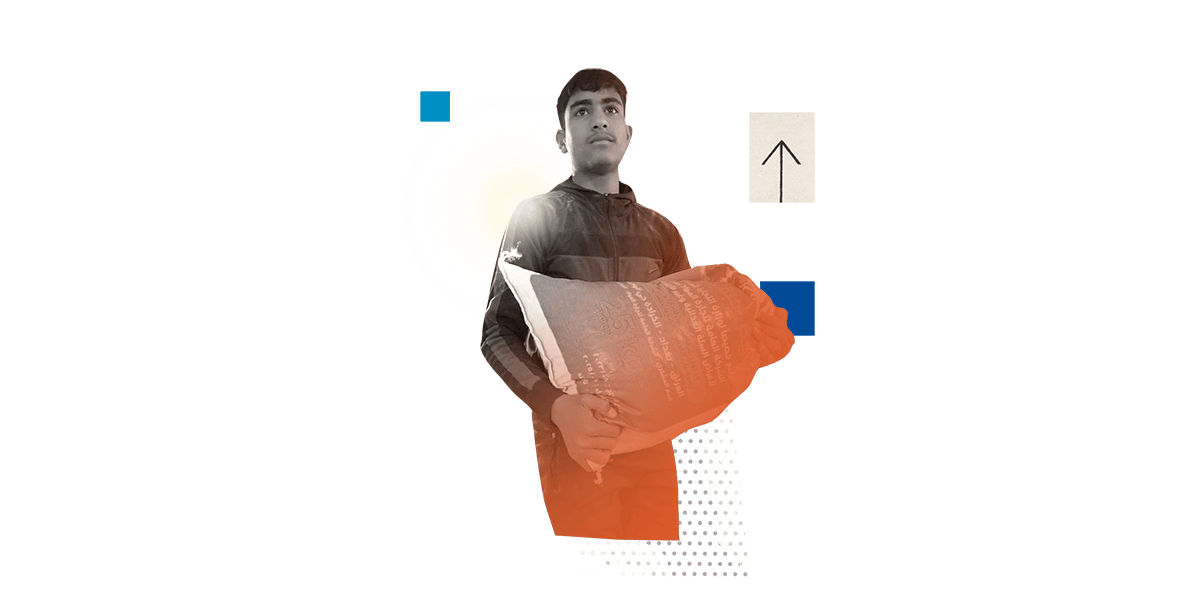

The potential ramifications of increasing AI usage are potentially profound. AI could herald the start of a technological revolution, which could jump-start productivity, boost global growth, and raise incomes around the world. Simultaneously, it could also replace jobs and deepen inequality. Those who can harness AI could experience an increase in their productivity and wages, while those who cannot risk falling behind.

According to one recent IMF paper, about 60 percent of jobs in advanced economies may be affected by artificial intelligence (AI). In emerging markets and low-income countries, that figure is expected to be 40 and 26 percent, respectively.

According to one recent IMF paper, about

of jobs in advanced economies may be impacted by artificial intelligence (AI).

Figure 1.4

Effects of AI on Jobs Could Be Profound

(AI performance on human tasks; human benchmark = 0; initial AI performance = -100)

Sources: Kiela and others 2021; OpenAI; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure is based on a number of tests in which human and AI performance were evaluated in five different domains, from handwriting recognition to language understanding. For the GRE mathematics test, the human benchmark is set at the median percentile, with ‑100 in 2017 reflecting the publication of the seminal paper on GPTs. AI = artificial intelligence; GPT = generative pretrained transformer; GRE = Graduate Record Examination.

Despite the potential gains, policymakers will have to proactively address the overall inequality caused by AI. To help countries craft the right policies, the IMF has developed an AI Preparedness Index that measures readiness in areas such as digital infrastructure, human-capital and labor-market policies, innovation, economic integration, and regulation and ethics. Wealthier economies, including advanced economies and some emerging market economies, tend to be better equipped for AI adoption than low-income countries, though there is considerable variation across countries.

Ensuring that the benefits of this potential revolution are more evenly shared, not only within countries but also between regions and countries, may require a reallocation of capital and labor from less-developed regions.With sufficient investment, AI may help emerging market and developing economies leapfrog in certain sectors, facilitating the offshoring of a broader selection of tasks and so reducing cross-country inequality.

The unpredictability of these forces—fragmentation, conflict, digitalization, and AI—translates into a more shock-prone world. Economies will need to become more resilient—not just individually but also collectively. To this end, there is much to be gained from engaging multilaterally. For example, the international community could scale up assistance and develop financing solutions that support peace and stability as global public goods. Supported by institutions such as the IMF, countries will need to work together to pursue targeted progress where common ground exists and maintain collaboration in areas where inaction would be devastating.

Toward a Greener Planet: The IMF, Climate, and Climate Financing

Climate change is a major threat to long-term growth and prosperity in all countries. The IMF helps its members address the challenges and risks caused by climate change through macroeconomic and financial policy advice, surveillance, capacity development, and lending.

This past financial year, the IMF continued to mainstream climate-related risks and opportunities into its policy advice. Part of the October 2023 Fiscal Monitor—one of the IMF’s flagship publications—was devoted to discussion of the fiscal policies appropriate for a warming world. The report concluded that the best way to achieve climate goals and maintain debt sustainability in a politically feasible way is through a carefully calibrated mix of revenue and spending-based policies. It advocated carbon pricing, or its equivalents, as a necessary instrument to help meet climate goals, complemented by measures to address market failures. It also encouraged private financing as well as investment in low-carbon technologies with transfers to protect the vulnerable during the green transition.

The IMF adds significantly to the stock of knowledge on the fiscal and macro-critical impact of climate change. In the past financial year, four Staff Climate Notes were issued and more than 550 publications covered climate issues during the same period.

Climate considerations have also played a part in IMF lending. The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) provides affordable long-term financing to help countries implement policy reforms that reduce macro-critical risks, including from climate change. Over the past financial year, 13 countries received funding commitments from the RSF. This is in addition to the five that benefited from the facility in the previous year. In all, three-quarters of the IMF’s 190 member countries are eligible for the RSF. (For more on the RSF, see the “Lending” section.)

Over the past financial year, the IMF has continued to support its members through capacity development in countries vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters. The organization leverages a range of tools and offers Climate Change 101 training to help build knowledge at finance ministries and central banks.

The Climate Finance Monitor—tracks and analyzes global financial flows for climate change mitigation and adaptation. It provides comprehensive data, insight, and guidance on climate financing, which leads to more informed and appropriate policies and actions.

Further progress in the area of climate change was reported in November 2023 when the IMF issued a progress report on the implementation of the Group of Twenty Data Gaps Initiative (DGI-3). Of the 14 recommendations in the report, 7 are related to climate change, the area of greatest progress. The IMF continued the dialogue on economic and financial sector policies in pursuit of shared climate goals during the COP28 Climate Change Conference in Dubai last year. At the conference, it contributed to the first global stocktaking of progress on the Paris Agreement and shared a pavilion with the World Bank Group and the Financial Times to present opportunities for knowledge exchange. Discussions centered on reducing emissions, boosting climate financing, increasing resilience to climate shocks, and easing the transition to low-carbon economies.

Together, these initiatives and contributions highlight the IMF's continued commitment to addressing the macro-critical consequences of climate change facing member countries.