Shopfront in Kenya. Strong business environment helps economic diversification (photo: Harry Hook/Getty Images)

Shopfront in Kenya. Strong business environment helps economic diversification (photo: Harry Hook/Getty Images)

Sub-Saharan Africa: Restarting the Growth Engine

May 9, 2017

Related Links

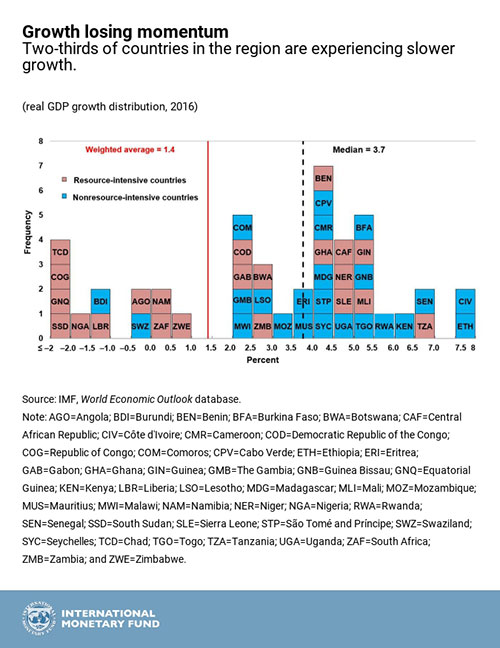

Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth has fallen to its lowest level in more than 20 years, the IMF said in its latest Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa.

While some countries like Senegal and Kenya continue to experience growth rates higher than 6 percent, growth has slowed for two thirds of countries in the region bringing down average growth to 1.4 percent in 2016.

A modest recovery in growth, to 2.6 percent, is expected in 2017, but the report said the underlying regional momentum remains weak, and at this rate, sub-Saharan African growth will continue to fall well short of past trends of 5-6 percent, and barely exceed population growth.

Why has growth slowed?

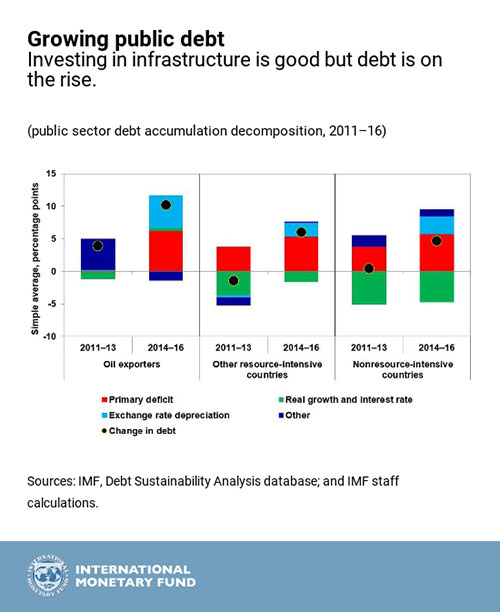

While noting that many countries suffered a very substantial commodity price shock, the report also points to insufficient policy adjustment to account for the broad-based slowdown in growth momentum in the region. This is especially the case among commodity exporters, notably oil exporters, such as Angola, Nigeria, and the countries of the Central African Economic and Monetary Union (CEMAC). According to the report, the delay in implementing critical adjustment policies is leading to higher public debt, creating uncertainty, holding back investment, and risks generating even deeper difficulties in the future.

Vulnerabilities are also emerging in countries that do not rely significantly on commodities for their exports. While these countries—such as Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Senegal—have generally maintained high growth rates, their fiscal deficits have been high for years, as governments rightly sought to address social and infrastructure gaps. But now, consequently, public debt and borrowing costs are on the rise.

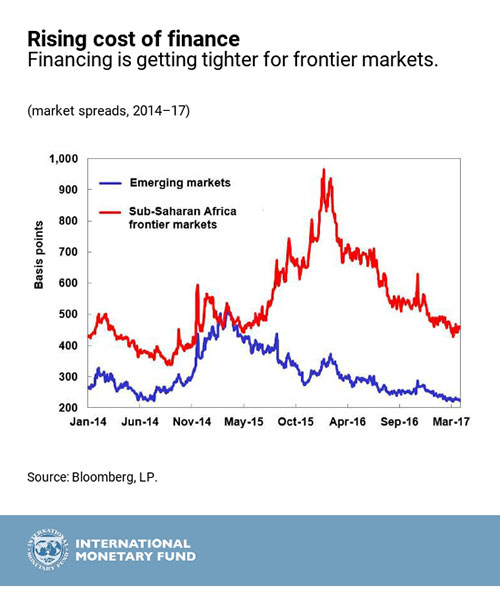

No room for complacency

The report also shows that, while the external environment has recently become more favorable, it is expected to offer only limited support. Improvements in commodity prices will provide some breathing space, but will not be enough to address existing imbalances among resource-intensive countries. Oil prices for example, are projected to stay far below their 2013 peaks. Likewise, while they have been on a declining trend since early 2016, financing costs for frontier economies in the region remain higher than for other emerging markets, and they could rapidly tighten further against the backdrop of fiscal policy easing and monetary policy normalization in the United States.

The outlook is also clouded by the incidence of drought, pests, and security issues, according to the report. While the impact of the drought that hit parts of southern Africa last year is fading, food insecurity appears to be rising with parts of southern and eastern Africa facing drought and pest infestations. Worse still, famine has been declared in South Sudan and is looming in northeastern Nigeria as a result of past and ongoing conflicts.

Policy priorities to restart growth engine

With all these challenges, the head of the IMF’s African Department, Abebe Aemro Selassie, says strong policy decisions could turn things around. “Sub-Saharan Africa remains a region with tremendous potential for growth in the medium term, but with limited support expected from the external environment, strong and sound domestic policy measures are urgently needed to reap this potential,” Selassie said. And the report highlights three priority areas.

The priority should be to put renewed focus on macroeconomic stability in order to set the stage for a growth turnaround. For the hardest-hit countries, fiscal consolidation remains urgently needed to halt the decline in international reserves and offset budgetary revenue losses, especially in the CEMAC. In addition, where available, greater exchange rate flexibility and the elimination of exchange restrictions will be important to absorb part of the shock. Meanwhile, for countries where growth is still strong, it will be important to address emerging vulnerabilities from a position of strength.

The second priority is to address structural weaknesses to support macroeconomic rebalancing. Structural measures are needed to ensure a sustainable fiscal position and help achieve more durable growth by improving tax collection, strengthening financial supervision, and addressing longstanding weaknesses in business climate that impede economic diversification.

Finally, the third priority should be to strengthen social protection for the most vulnerable people. The current environment of low growth and widening macroeconomic imbalances risks reversing recent progress made in alleviating poverty. Existing social protections programs are often fragmented, not well-targeted, and cover a small share of the population. The report suggests savings from expansive and untargeted schemes such as fuel subsidies could be put towards helping vulnerable groups.

In two background studies, the Regional Economic Outlook also examines the region’s experience with episodes of sustained growth and what drove them, as well as the role of the informal sector in sub-Saharan Africa.