Pacific island countries are eager to leverage the opportunities of the digital money revolution by developing payment systems, expanding financial inclusion, and mitigating the loss of correspondent banking relationships.

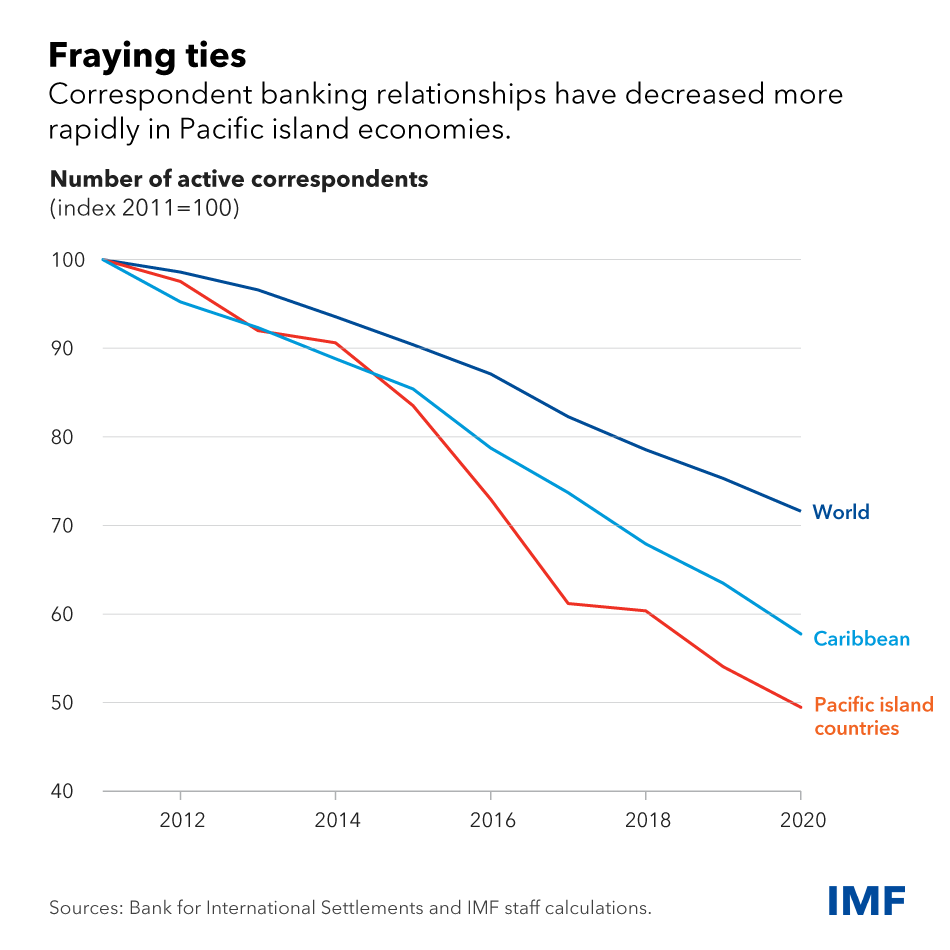

These countries, some of the world’s most remote and dispersed, face challenges to financial services and inclusion, partly due to their small size and unique landscape. Limited and unequal access to financial services contributes to persistent poverty and inequality. The countries also are highly dependent on remittance flows, which makes them disproportionately impacted by diminishing correspondent banking relationships.

Our latest research explores the potential role of digital money in the region, including stablecoins, and central bank digital currency, or CBDC. We do not include unbacked crypto assets in our discussion as they do not meet the definition of money.

In an increasingly interconnected world, digital money and related innovation offer advantages such as efficiency, accessibility, and security. Digital money that’s well designed and governed can help realize policy objectives such as financial inclusion and greater cross-border connectivity. It can help empower previously underserved people and groups, providing them with access to financial services and government support.

Conversely, adopting digital money without adequate preparation and safeguards can disrupt economies and financial markets. Prolonged interruptions can even cause serious financial stability risks in countries that don’t have the proper capacity. Digital money could also introduce new threats from money laundering and terrorist financing.

Pacific island countries and other similar countries are constrained by scale and resources in introducing digital money. The digital infrastructure and institutional frameworks—legal, regulatory, and supervisory—needed for successful digital money implementation tend to be underdeveloped. In addition, many countries in the region can’t afford high development costs, such as those for training, operations, and technology development.

Embracing digital money requires underlying infrastructure that’s stable, secure, and accessible. Service providers should be encouraged to develop business models that generate sustained revenue and cover costs. Digital money also must be attractive to use, including by tourists, as they provide a large share of national income for many countries in the region. The legal status of digital money should be clear, as should the obligations of service providers, user rights, and the responsibilities of supervisory and other authorities.

Policy considerations

Ultimately, digital money decisions should depend on a variety of monetary and financial conditions, such as the existence or not of a national currency and the maturity of domestic payment systems, besides having in place adequate institutional capacity. Countries with a national currency may eventually be able to introduce a CBDC at some point in coming years.

The maturity of the banking and payment-service provider industries may help indicate what type of digital money or design choices work best for Pacific island countries. For example, a two-tier CBDC (whereby the central bank issues but delegates the operation to private intermediaries) may be best for countries with national currency and mature banks and payment providers. Elsewhere, foreign currency–based stablecoins could be a realistic alternative for countries without their own currencies, though only with robust regulation and supervision.

Pacific island countries could explore a regional approach to introducing new forms of digital money and payments while managing the associated risks. That could entail connecting traditional domestic payment systems, interlinking CBDCs once in place, establishing or joining multilateral digital payment platforms and regional networks. And it can include knowledge sharing with peers, development partners and international organizations like the IMF.

For its part, the IMF has provided training and technical assistance in the region for three decades, including through our Pacific Financial Technical Assistance Center, and helped by bringing together peers and senior policymakers from other regions to share their experiences.

—This blog, based on the departmental paper Rise of Digital Money: Implications for Pacific Island Countries, reflects research contributions from Tao Sun, Arvinder Bharath, Stephanie Forte, Kathleen Kao, Yinqiu Lu, Maria Fernanda Chacon Rey, Piyaporn Sodsriwiboon, Chia Yi Tan and Bo Zhao. For more on the Fund’s work in the region, see the recent commentary by Deputy Managing Director Bo Li and Marshall Mills, who leads the Pacific Islands Division and is mission chief for Fiji.