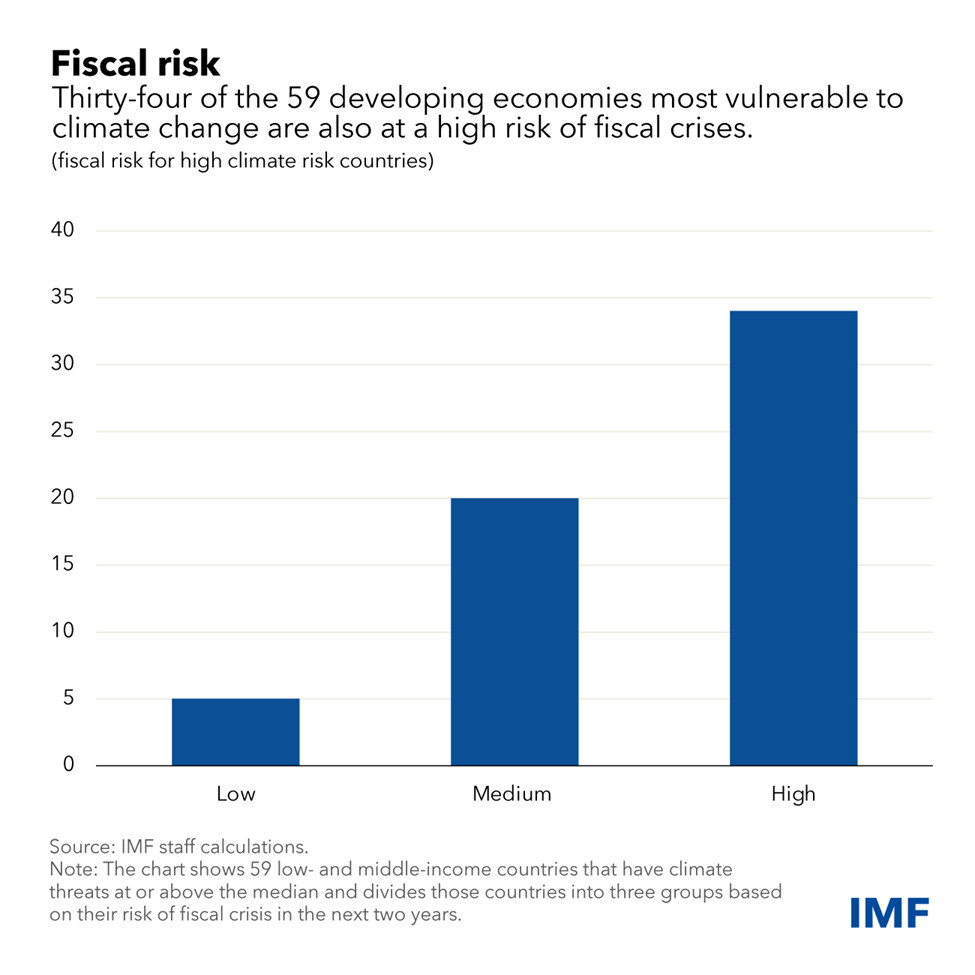

Countries that are most vulnerable to climate change—and the associated loss of natural biodiversity—are often those least able to afford investment to strengthen resilience because their budgets are burdened by debt. Such countries face a high risk of fiscal crisis, IMF staff research shows.

Debt-for-climate swaps and debt-for-nature swaps seek to free up fiscal resources so that governments can improve resilience without triggering a fiscal crisis or sacrificing spending on other development priorities. Creditors provide debt relief in return for a government commitment to, say, decarbonize the economy, invest in climate-resilient infrastructure, or protect biodiverse forests or reefs.

These instruments have existed in various forms for decades, and more countries are considering them following recent agreements in Barbados, Belize and Seychelles.

In cases where action would not have been taken without the swap, the arrangement aids climate action or protects nature. And to the extent that debt reduction exceeds the new spending commitments, borrowers get fiscal relief through budget savings. There can be other benefits, too, such as an upgrade to a country’s sovereign credit rating, as was the case in Belize, which makes government borrowing cheaper.

Swaps could even create additional revenue for countries with valuable biodiversity by allowing them to charge others for protecting it and providing a global public good. This is also true of carbon sinks, or natural environments which absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and are an important part of the transition to a lower carbon economy.

In most cases, it’s more effective to address debt and climate or nature separately.

For example, a simple climate-conditional grant tends to be more efficient on the climate side without the added complexity of a debt-swap operation.

For countries with unsustainable debt, a swap cannot restore solvency unless it involves a sufficiently large share of a country’s debt and substantial relief—an extreme case. So far, no swap has come close to achieving this.

Swaps are thus not substitutes for debt restructuring when it is needed. Instead, a broad-based restructuring (through the Group of Twenty’s Common Framework,for instance) would best restore solvency. Measures to support climate or conservation investment could then follow.

That said, grants and concessional loans from bilateral donors and multilateral development banks are scarce relative to the enormous need for climate and nature financing, particularly for middle-income countries that do not normally qualify for grants. And restructuring is often not available to countries until their debts become unsustainable and they lose market access.

Under these circumstances, it may not be feasible to deal with the issues separately. Swaps may then be among the few tools that are available to help with both debt and environmental objectives. So there are circumstances in which they can complement other climate-finance instruments.

Need to scale up transactions

Yet for swaps to really have an impact, the number and size of transactions must be scaled up significantly. This means addressing barriers to scale and improving the financial terms under which swaps are conducted.

There are several ways to help swaps progress from niche products, often linked to small projects that are expensive to structure and monitor, to more mainstream instruments.

IMF staff have proposed: structuring deals around broad climate and environmental goals such as de-carbonizing the energy industry, investing in adaptation, or protecting nature; moving away from custom projects and supporting budgetary spending on climate in countries with strong public financial management and policy credibility; and linking swaps to simple-to-monitor metrics such as carbon emissions, deforestation, or ocean exploitation.

In addition, the fiscal space that is created by swaps could be increased by improving the terms of the transaction in three ways:

- Include as large a share of a country’s debt as possible. This requires

more financing and, to this end, more third parties such as governments,

foundations and civil-society organizations could be encouraged to buy debt

on secondary markets and use it for climate or nature swaps.

- Repurchase debt at the lowest possible price, through carefully designed

secondary-market transactions that minimize the increase in price as debt

is bought back, or through incentives for creditors, such as allowing them

to trade in carbon credits arising from the transaction.

- Minimize the cost of financing the debt buy-back. As in the above transactions, donors could offer partial guarantees that lower the risk for investors and reduce the expense.

While other institutions with relevant expertise must be involved and the market participants able to arrange these complex transactions increased, the IMF can play an important supporting role. Through annual Article IV consultations, financing arrangements and capacity development, the Fund can help countries develop macroeconomic and budget frameworks to integrate the impact and thus support the use of swaps. Our debt sustainability analysis now includes the impact of natural disasters and climate change.

Our new Resilience and Sustainability Trust could support resilience-enhancing climate-related policy reforms with affordable long-term financing. The resources could potentially be used to buy back expensive debt in cases where this meaningfully reduces the debt-servicing burden. The Trust also aims to catalyze additional official and private financing.

Reforms in the context of Fund-supported programs could allow country authorities to signal their policy ambitions, and possibly encourage parties interested in swaps. Promising avenues include energy sector reforms or the greening of public financial management.

In sum, swaps can play a role in some circumstances. They are unlikely to provide a universal solution for countries struggling with debt or confronting climate change or nature loss. And they should not come at the expense of traditional debt relief or concessional finance. However, they can be scaled up to complement existing instruments and strengthen resilience in countries on the front line of climate change and loss of natural biodiversity at a time when financing is scarce.