Companies around the world are engaged in a digital data gold rush, panning the digital economy for our personal data, sifting flecks of it in online pools and streams of our preferences, choices, and locations. Data is the ultimate portable good, but moving it across borders requires countries to have coherent policies that build trust. Without global principles for managing data, we could face deepening digital fault lines between nations, as massive data pools become increasingly isolated. This would be especially costly for smaller and lower-income countries.

Policies to protect privacy can help lessen the unauthorized use of personal data.

Our data power artificial intelligence (AI) that can make societies more productive, driving growth, employment, and finance. Think of more efficient supply chains, vaccine breakthroughs, and lending to previously unbanked small businesses around the world. But there are also dark sides. More and more data can be captured without our effective consent by large platforms, such as Alibaba, Facebook, Google and MercadoLibre, whose valuations have grown exponentially in recent years.

Cross-cutting issues

A new IMF staff paper discusses these challenges for growth, stability, and the international system, which are at the core of the IMFs mandate and makes the case for global cooperation to address them. Policymakers will need to start by recognizing they face several key challenges spanning financial stability and inclusion, competition, and privacy.

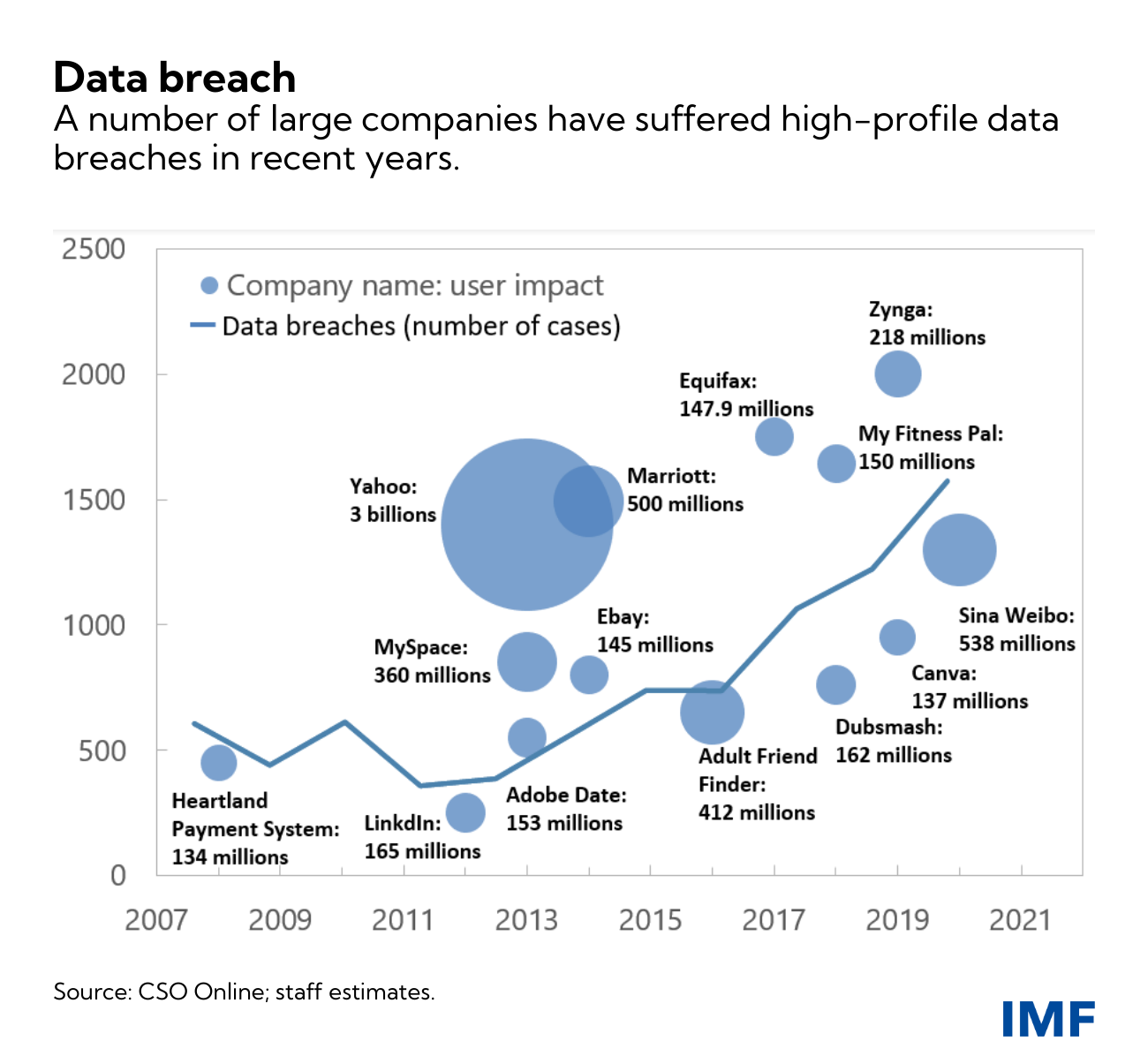

Fostering competition and stability in the digital economy: The concentration of data in large platforms reduces competition and increases the risks of hacking and single points of failure in modern economic and financial networks (seen in recent widespread service disruptions). Indeed, cyberattacks have been a key challenge in the data economy.

Promoting inclusive digitalization: Data can support greater efficiency and inclusion, including in the provision of financial services, as we have seen with the boom in fintech credit in many emerging and developing countries. But it can also be used by monopolists for price discrimination, raising profits at the expense of customers. Data-driven analytics could also be used to exclude some people from economic and financial services based on socioeconomic or other personal characteristics (what is known as “algorithmic bias”). This can disadvantage or exclude some individuals from important services that society views as essential, such as AI-driven credit scoring that worsens racial bias in mortgage lending, or facial recognition technology that fails to recognize darker skin tones.

Balancing privacy trade-offs: Policies to protect privacy—an important objective in most countries—can help lessen the unauthorized use of personal data. Privacy of financial and medical data, for example, is a key underpinning of trust in these systems. However, solely focusing on protecting privacy may prevent other uses of data that generate economic and social value—for example from sharing anonymized data on vaccine trials across borders—and may make it hard for start-ups to obtain the data they need to compete against data-rich incumbents. Clear rules are needed to tackle these trade-offs, including giving people effective control over their data while balancing public policy needs for certain types of data disclosure.

Moving toward global principles

Addressing these challenges should start at home. A number of new policy tools and approaches are being considered to provide solutions to these challenges at a domestic level. Policymakers will need to continue their focus on developing the updated laws, systems, and procedures for regulating data collection and use. At the same time, they will also need to consider mandates for making networks compatible with each other and allowing users to move and store their data on different networks.

Furthermore, policymakers could consider whether and how agencies could be created to manage consent and protect privacy, as well as provide data as a public good. Setting up “data fiduciaries”—where third-party companies collect and share data on behalf of individuals (as being explored in India)—or the data equivalent of credit bureaus (for broader classes of data beyond finance) are ideas to think about here. Balancing all the trade-offs will require unprecedented cooperation among regulators and government agencies responsible for competition, financial stability, integrity, consumer protection, and privacy.

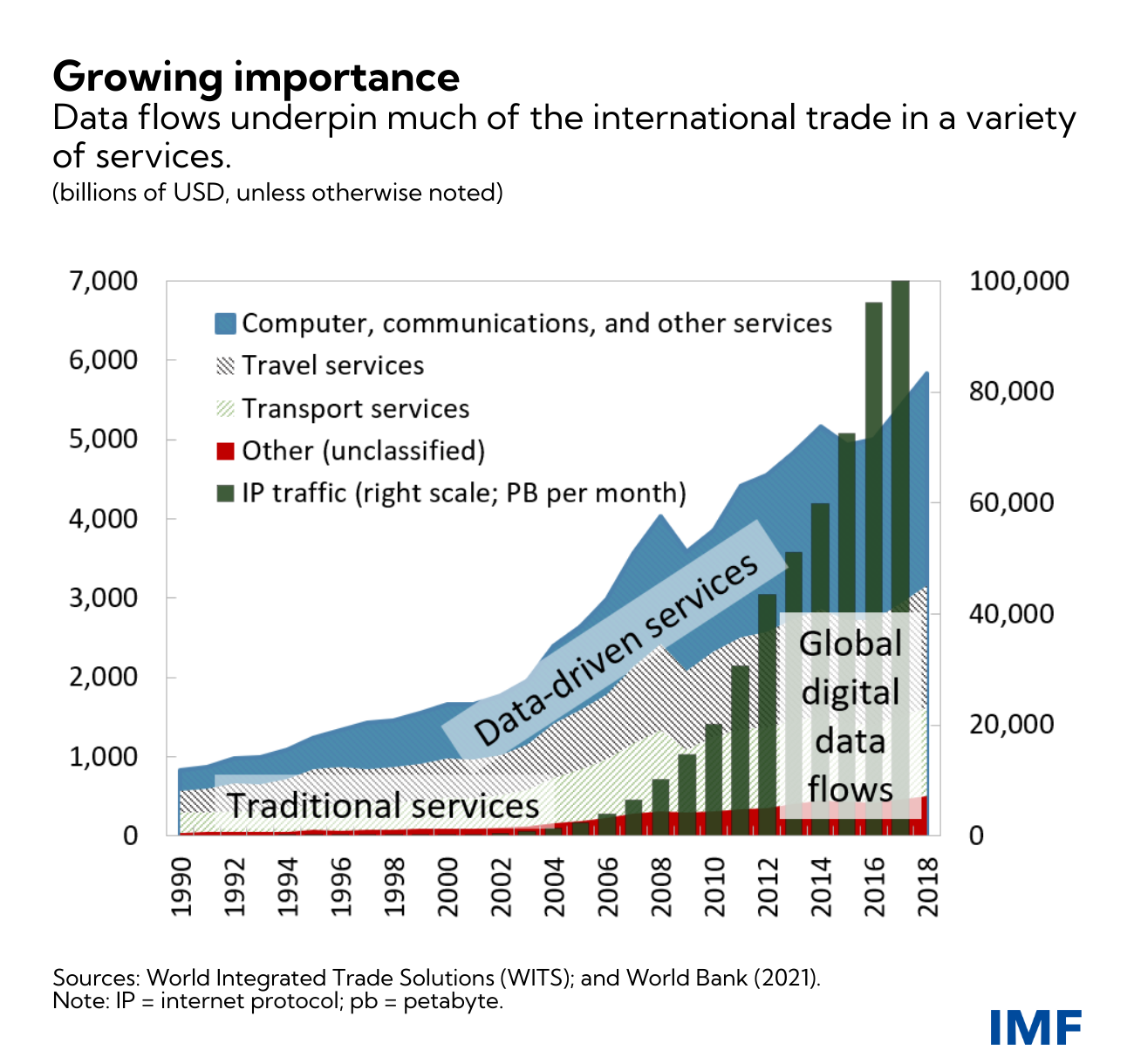

But these issues are global. The mobility of data across borders is the basis for a rapidly growing portion of international trade in services, whose value reached about 6 trillion dollars in 2018. So, given the risk of further policy divergencies, cooperation among countries will be critical to help prevent fragmentation from taking hold in the global digital economy.

Needed—a common approach on data

Countries’ treatment of privacy, competition, and stability reflects their national priorities. And the resulting fragmentation could be damaging to smaller countries with smaller data pools and those more dependent on multinational digital firms. For example, strong privacy protections in some advanced countries may work as trade barriers for exporters of services from developing nations whose businesses have to incur exceptional costs to comply with protections.

Therefore, a strong case exists for common global principles for the data economy. For example, a common understanding of definitions in government rules to protect personal privacy, as well as to what kinds of firms and business activities they should apply, could help reduce some of the policy divergences among countries.

Many of the other domestic policy approaches being proposed for managing the data economy—for example, requirements that data be more easily shared across platforms to promote competition or on how to manage an individual’s consent—could also benefit from common principles on their international application. Provided privacy concerns can be adequately addressed, there is scope for international coordination on compilation and sharing of data sources from private digital companies for regulatory and public policy purposes.

As domestic and international efforts advance, the tensions between data privacy, security, competition, and stability will continue to play out in the global digital economy.