The pandemic has rolled back decades of economic progress and wrought havoc on public finances. To build back better and fight climate change, sizable public investment needs to be sustainably financed. Boosting long-term growth—and thereby tax revenue—has rarely felt more pressing.

But what are the drivers of long-term growth? Productivity—the ability to create more outputs with the same inputs—is an important one. In our latest World Economic Outlook, we emphasize the role of innovation in stimulating long-term productivity growth. Surprisingly, productivity growth has been declining for decades in advanced economies despite steady increases in research and development (R&D), a proxy for innovation effort.

Knowledge transfer between countries is an important driver of innovation.

Our analysis suggests that the composition of R&D matters for growth. We find that basic scientific research affects more sectors, in more countries and for a longer time than applied research (commercially oriented R&D by firms), and that for emerging market and developing economies, access to foreign research is especially important. Easy technology transfer, cross-border scientific collaboration and policies that fund basic research can foster the kind of innovation we need for long-term growth.

Inventions draw on basic scientific knowledge

While applied research is important to bring innovations to market, basic research expands the knowledge base needed for breakthrough scientific progress. A striking example is the development of COVID-19 vaccines, which in addition to saving millions of lives has helped bring forward the reopening of many economies, potentially injecting trillions into the global economy. Like other major innovations, scientists drew on decades of accumulated knowledge in different fields to develop the mRNA vaccines.

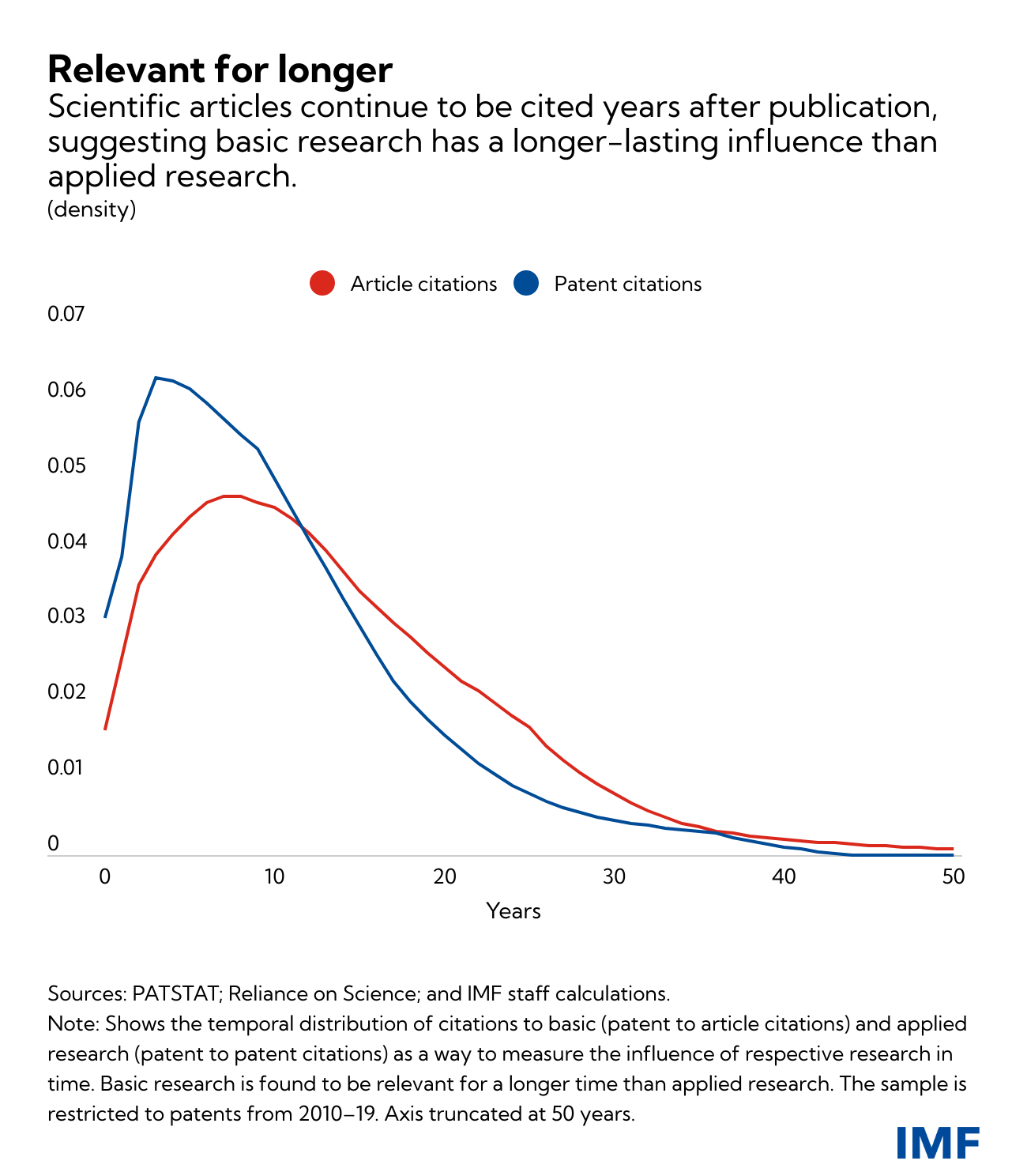

Basic research is not tied to a particular product or country and can be combined in unpredictable ways and used in different fields. This means that it spreads more widely and remains relevant for a longer time than applied knowledge. This is evident from the difference in citations between scientific articles used for basic research, and patents (applied research). Citations for scientific articles peak at about eight years versus three years for patents.

Spillovers are important for emerging markets and developing economies

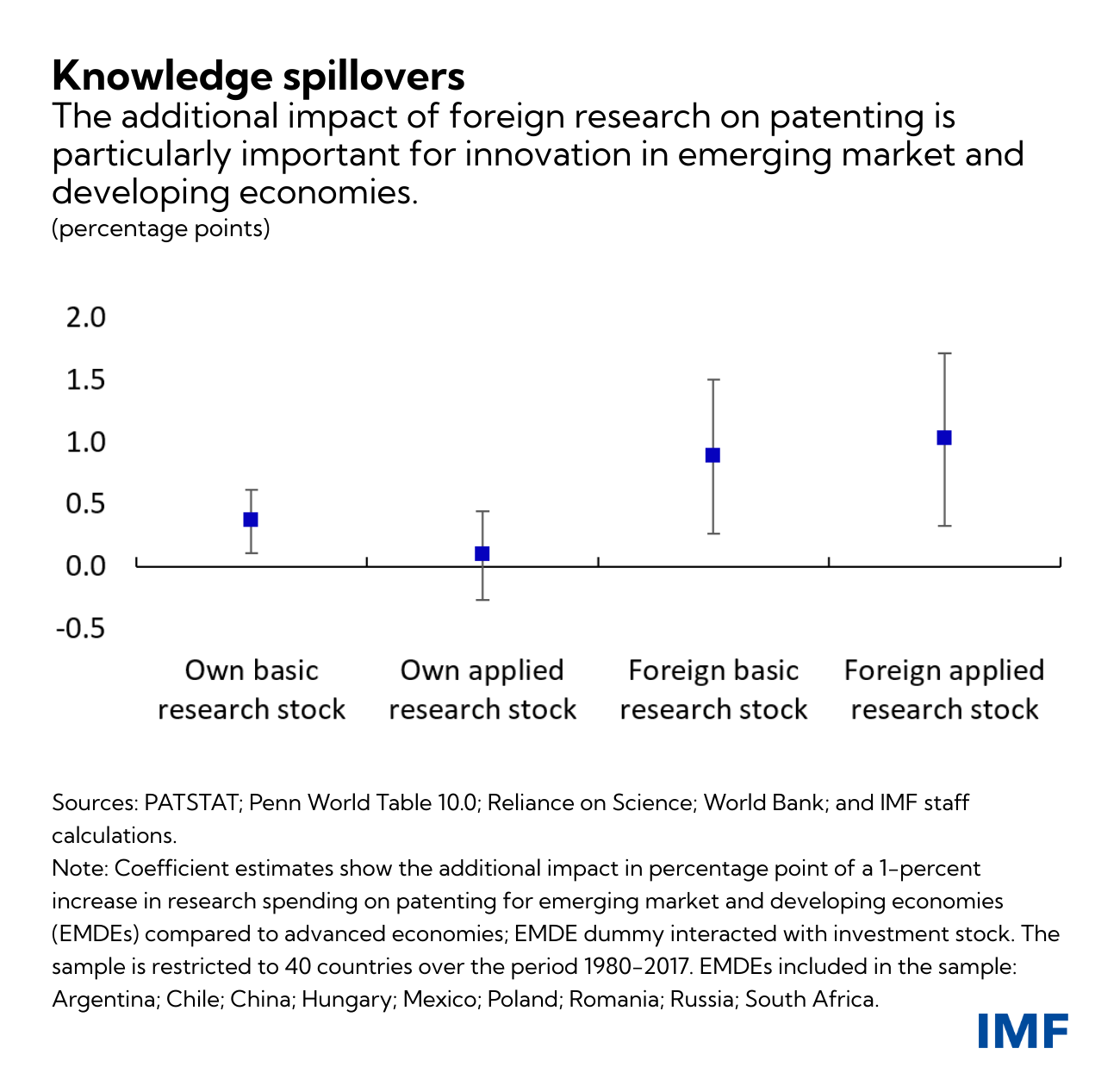

While the bulk of basic research is conducted in advanced economies, our analysis suggests that knowledge transfer between countries is an important driver of innovation, especially in emerging market and developing economies.

Emerging market and developing economies rely much more on foreign than homegrown research (basic and applied) for innovation and growth. In countries where education systems are strong and financial markets deep, the estimated effect of foreign technology adoption on productivity growth—through trade, foreign direct investment or learning-by-doing—is particularly large. As such, emerging market and developing economies may find that policies to adapt foreign knowledge to local conditions are a better avenue for development than investing directly in homegrown basic research.

We gauge this by looking at data on research stocks—measures of accumulated knowledge through research expenditure. As the chart shows, a 1-percentage-point increase in foreign basic knowledge increases annual patenting in emerging market and developing economies by around 0.9 percentage point more than in advanced economies.

Innovation is a key driver of productivity growth

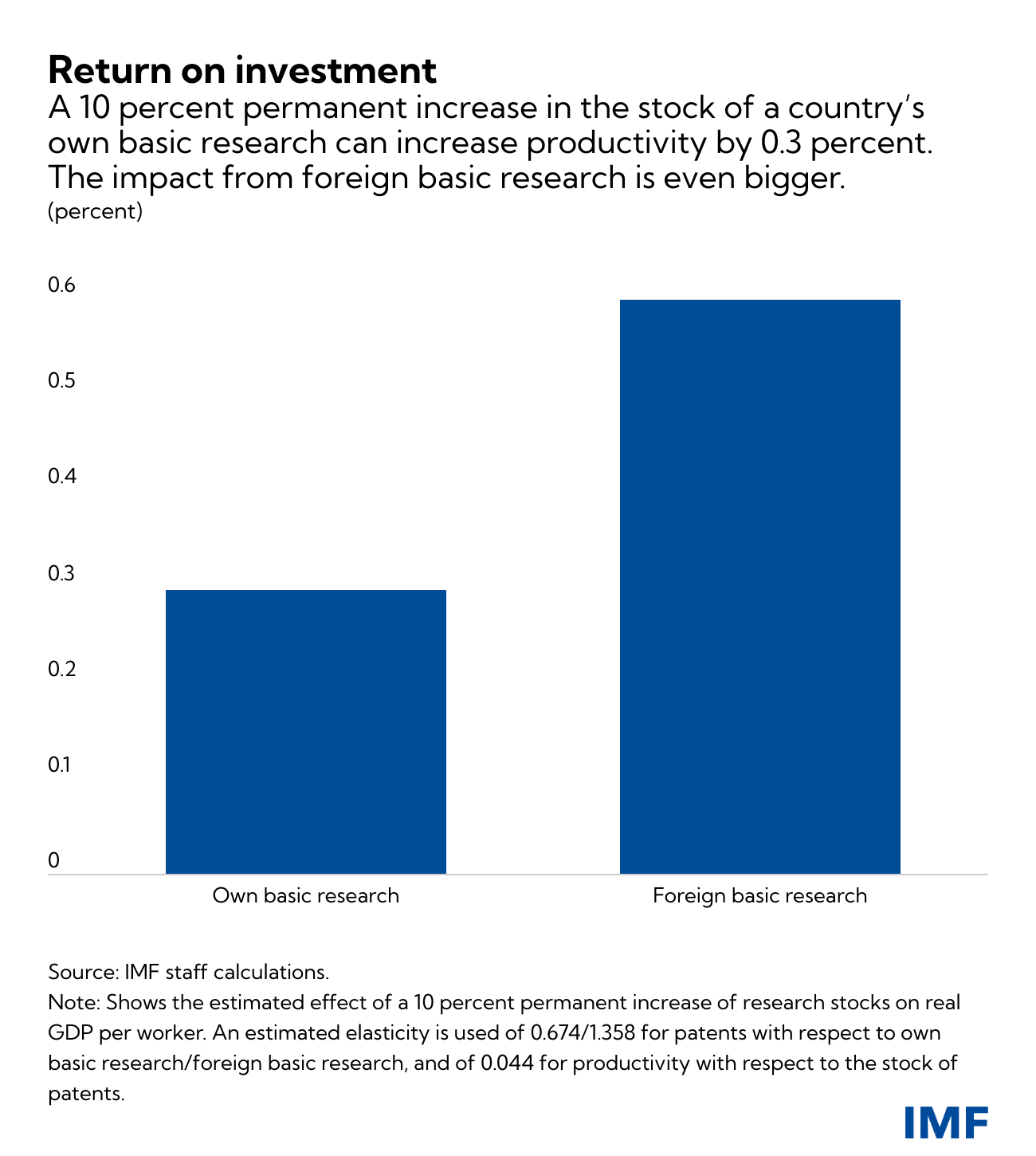

Why does patenting matter? It’s a proxy for measuring innovation. An increase in the stock of patents by 1 percent can increase productivity per worker by 0.04 percent. That may not sound like much, but it adds up. Small increases over time improve living standards.

We estimate that a 10 percent permanent increase in the stock of a country’s own basic research can increase productivity by 0.3 percent. The impact of the same increase in the stock of foreign basic research is larger. Productivity increases by 0.6 percent. Because these are average numbers only, the impact on emerging markets and developing economies is likely to be even bigger.

Basic science also plays a larger role in green innovation (including renewables) than in dirty technologies (such as gas turbines), suggesting that policies to boost basic research can help tackle climate change.

Policies for a more buoyant and inclusive future

Because private firms can only capture a small part of the uncertain financial reward of engaging in basic research, they tend to underinvest in it, providing a strong case for public policy intervention. But designing the right policies—including determining how you fund research—can be tricky. For example, funding basic research only at universities and public labs could be inefficient. Potentially important synergies between the private and public sector would be lost. It may also be difficult to disentangle basic and applied private research for the sake of subsidizing only the former.

Our analysis shows that an implementable hybrid policy that doubles subsidies to private research (basic and applied alike) and boosts public research expenditure by a third could increase productivity growth in advanced economies by 0.2 percentage point a year. Better targeting of subsidies to basic research and closer public‑private cooperation could boost this even further, at lower cost for public finances.

These investments would start to pay for themselves within about a decade and would have a sizeable impact on incomes. We estimate that per capita incomes would be about 12 percent higher than they are now had these investments been made between 1960 and 2018.

Finally, because of important spillovers to emerging markets, it is also key to ensure the free flow of ideas and collaboration across borders.