From car manufacture to self-service checkouts, we all see how automation can transform the world of work—with lower costs and higher productivity on one hand, and more precarious employment for people on the other. But the COVID-19 pandemic added fuel to the fire. The rise in telework, for example, is hurting low-wage workers and increasing inequality. More broadly, if the pandemic accelerates the pace of automation, then we may face a jobless recovery for low-skilled workers. Our recent IMF staff research suggests that such concerns are justified.

Low-skilled workers are more at risk of displacement by robots than high-skilled workers, which reinforces existing inequality dynamics.

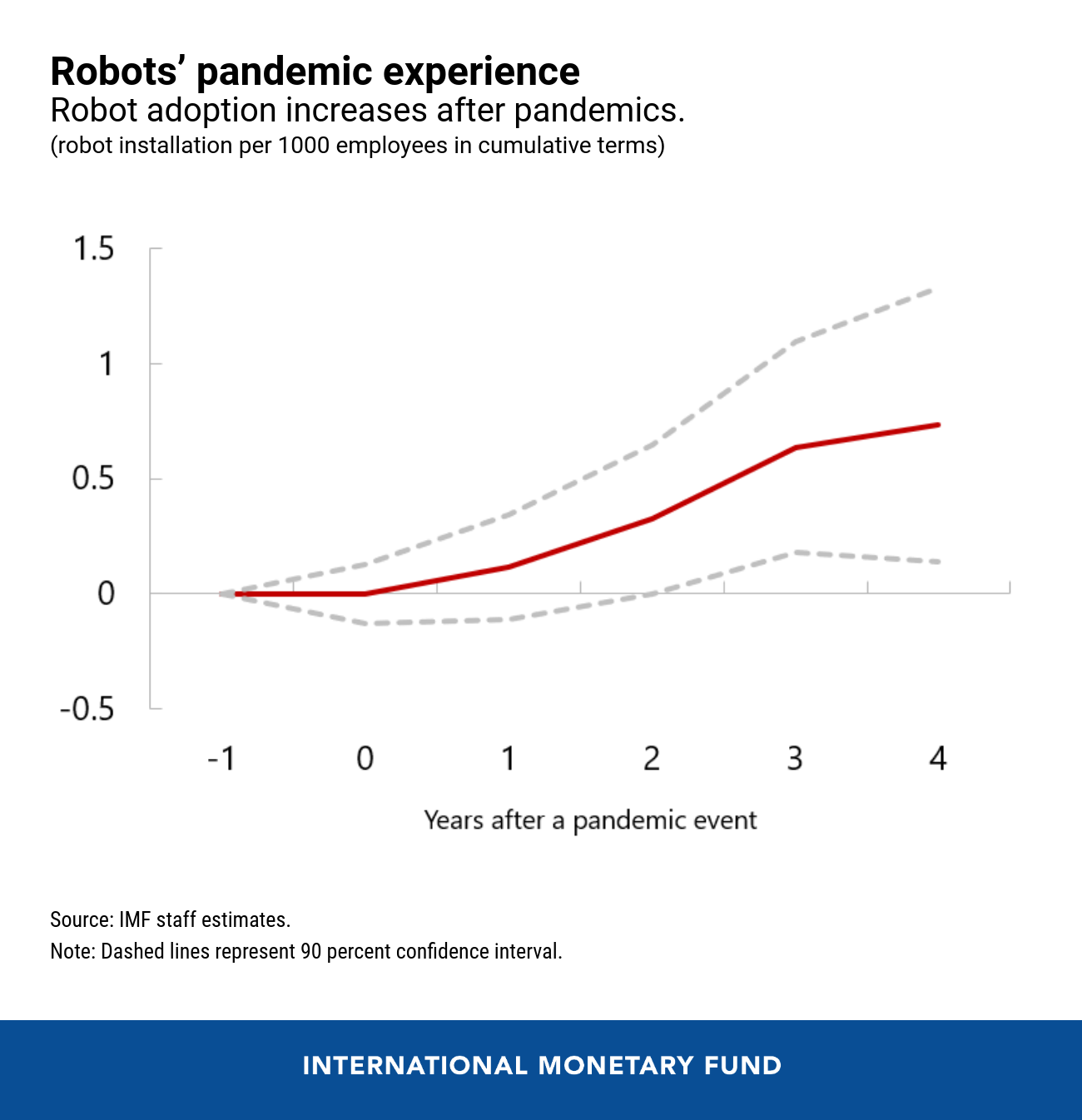

We focus on one form of automation, industrial robots, and analyze the effect of past major pandemics on their adoption: SARS in 2003, H1N1 in 2009, MERS in 2012, and Ebola in 2014. We use econometric techniques and robot data at the sectoral level from the International Federation of Robotics covering 18 industries in 40 countries between 2000 and 2018.

We find that robot adoption (measured by new robot installations per 1000 employees) increases after a pandemic event, especially when the health impact is severe and when the pandemic is associated with a significant economic downturn.

Why do pandemics lead to the rise of robots? We see two key reasons.

First, after large shocks like recessions, firms restructure their businesses and adjust production toward technologies that lower labor costs. Second, firms may prefer robots because they are immune from health risks. Pandemic-induced uncertainty also adds to incentives for automation, as firms try to make sure they can withstand the next pandemic.

The rise of robots and inequality

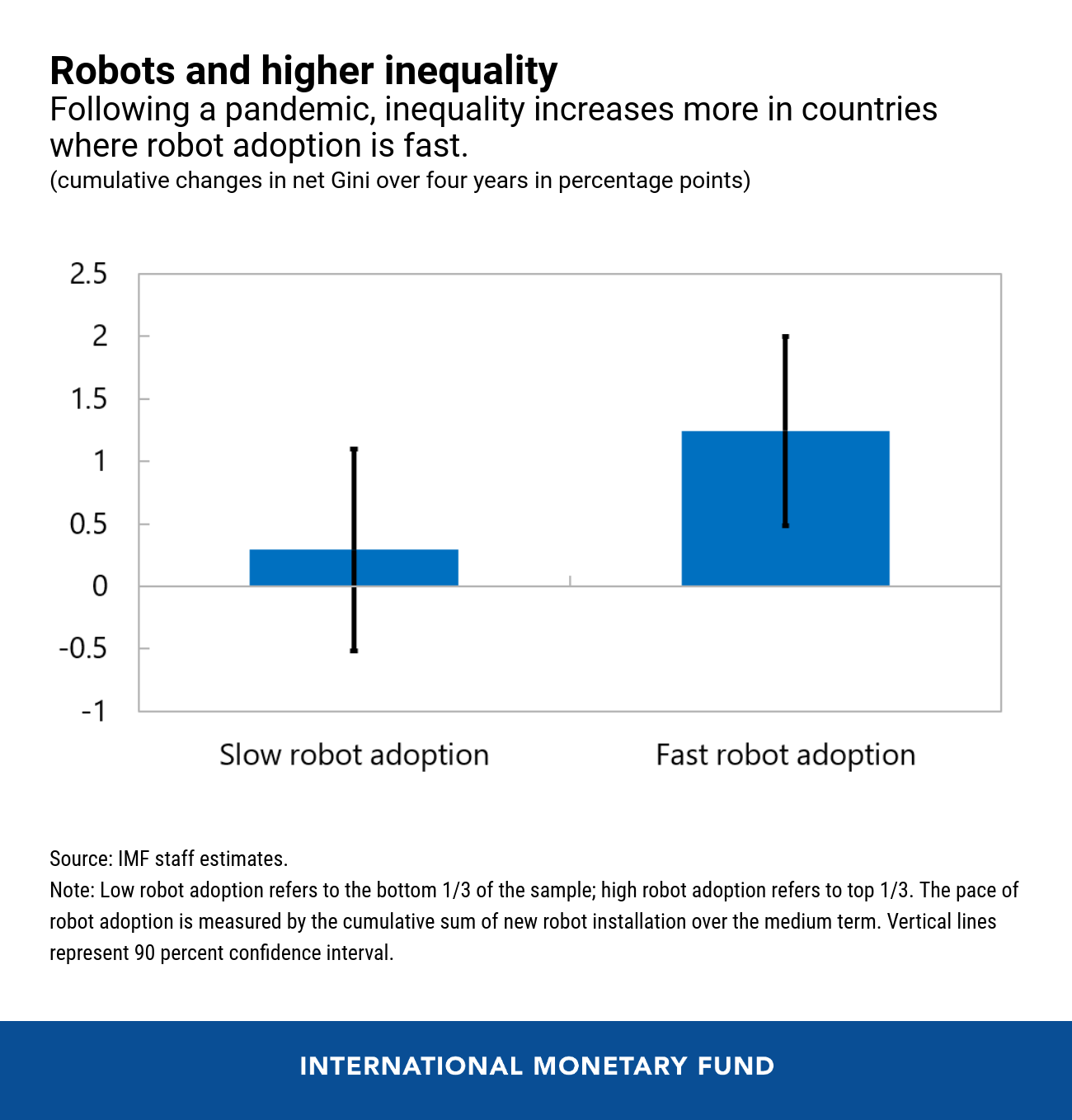

Robots do not affect all workers in the same way. Low-skilled workers are more at risk of displacement by robots than high-skilled workers, which reinforces existing inequality dynamics.

Looking at country-level data and a larger sample, we find that following a pandemic the increase in inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, over the medium term is larger where new robot adoption has increased more. Our results suggest that the acceleration of robotization is an important channel through which pandemics lead to higher inequality.

Looking forward, a corollary of our results is that while automation and robotization are accelerating from still-low levels, they will likely become even more important drivers of inequality in the future. Left unchecked, growing disparities may lead to long-lasting grievances and ultimately to social unrest, forming a vicious cycle.

Policymakers need to pay attention to preventing scarring effects on the livelihoods of the most vulnerable, including through appropriate labor market policies.

As automation intensifies following COVID-19 and transforms workplaces, more workers will need to find new jobs, especially those who are less skilled. Policies to mitigate rising inequality include revamping education to meet the demand for more flexible skill sets, and lifelong learning and new training—especially for the most affected workers. A good example is Singapore’s SkillsFuture initiative, which promotes learning in all stages of life to address the challenges brought by technological changes.

These measures may still fall short if the training involves acquiring a substantively different and challenging set of skills, raising the possibility of dropouts. It is therefore important for policymakers to consider ways to address medium-term social challenges, including through strengthened social safety nets.

While robotization is inevitable, its distributional outcome will depend on policies. A society that is more willing to provide support to those who are left behind can accommodate a faster pace of innovation, while ensuring that all members of society are better off.