Countries cooperate if they perceive it to be in their best interests, both economically and politically. Global cooperation in the aftermath of World War II—through a system of rules, shared principles, and institutions—has delivered major economic and social progress, lifting millions of people out of desperate poverty. And when countries joined ten years ago to coordinate their macroeconomic policies, they ensured that the Great Recession did not become another Great Depression. The first Group of 20 leaders’ summit in November 2008—bringing together the major advanced economies and big emerging economies like Brazil, China, and India—symbolized an urgent spirit of cooperation. Evidently, countries can achieve a lot when they pull together.

Yet, at a time when the world economy is more complex than ever and faces many shared challenges, some nations have become less willing to take collective action. The system of global cooperation is currently under stress.

Global cooperation has been critical to the impressive expansion of wellbeing and opportunities over the past seventy years.

There are understandable reasons for people to question the continuing benefits of international cooperation today. Economic inequality within nations is widening, especially in advanced economies. Many households have seen little benefit from economic growth, and many communities have suffered from losing jobs and whole industries. Voters are therefore readier to listen when politicians claim that global engagement prevents addressing problems at home.

But retreating from international cooperation would be a mistake, recreating some of the conditions that gave rise to past crises. Cooperative policies won’t happen, however, unless they have domestic political support. Thus, countries will lose out unless governments can show voters the concrete benefits from international cooperation.

International cooperation under stress

There are two main factors that have sapped people’s confidence in the benefits of economic cooperation.

First, while technological innovation and growing global trade have helped drastically reduce inequality between people living in different countries, they are part of the reason for greater inequality within many advanced economies. In the eyes of the public, trade seems to get the lion’s share of the blame, making people leery of expanding trade further through ever more economic integration.

Second, the very success of international cooperation since World War II has, over time, reduced the share of world economic activity taking place in advanced economies in Europe, the United States, and Japan, while increasing that of emerging markets.

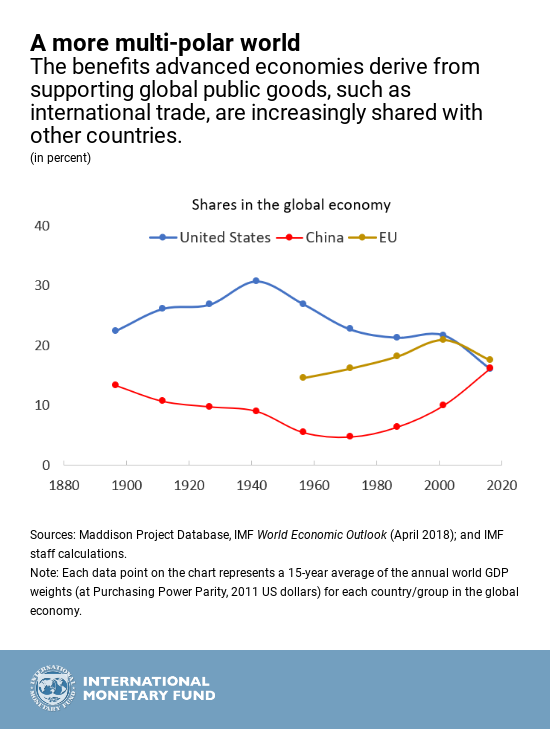

The chart shows this striking evolution since 1950. The benefits the United States and other advanced economies derive from supporting global public goods, such as international trade, are increasingly shared with other countries.

This development might help explain why the success of US-led globalization and international cooperation in boosting trade and per capita incomes around the world has, paradoxically, weakened public support for cooperation within the United States and other advanced economies. Cooperation is harder to maintain in today’s multi-polar world.

The enduring need for global cooperation

Notwithstanding these difficulties, countries need more―not less―multilateralism. Why? Because the world has become more interdependent than ever before.

For starters, the information revolution has increased connections and complexity all over the world. Ideas are flowing everywhere. Production has become increasingly international through global supply chains, as countries increasingly rely on foreign inputs for their own exports.

The list of shared problems is daunting. It includes: climate change, declining biodiversity, the risk of pandemics and superbugs, scarcity of clean water, oceanic degradation, cyber-crime, terrorism, large-scale migrations, and tax avoidance.

National borders are no match for these challenges; they require countries to cooperate.

Our world is also brought together by some socially damaging forms of trade, such as human, drug, and arms trafficking, as well as anonymous cross-border flows of ill-gotten funds. Again, individual national authorities are hard pressed for solutions. Collective action is vital.

Building greater support

That said, governments will resist the temptation of “us first” policies only if cooperation can attract broad public support. And that will happen only if international cooperation is perceived to mitigate legitimate and widely-held concerns related to the costs of globalization. Otherwise, voters are more likely to fall prey to political leaders offering siren songs of self-sufficiency.

This means all governments need to ensure that policies help those affected by dislocations, whether from trade or technological advances. It also means promoting policies that reduce inequality, broaden economic opportunity through investment in people, increase government transparency (especially of tax systems), and curtail corruption.

Over the past several years, the IMF has become increasingly focused on these issues in all aspects of its advice to countries.

Building support for cooperation will also require a certain amount of humility. The heady postwar days—when countries formally surrendered elements of their sovereignty, including exchange rate sovereignty—are behind us. The more important means of cooperation will rely on “soft” law, where countries collectively agree to apply best practices, such as the Basel Core Principles governing bank regulation, rather than “hard” law or legally binding treaty obligations.

Global cooperation has been critical to the impressive expansion of wellbeing and opportunities over the past seventy years. Now it must deliver results for the challenges of the 21st century. Meeting these challenges will require new modes of cooperation, better communication, and a global policy agenda that resonates broadly with the public.

In short, the world needs a new multilateralism.