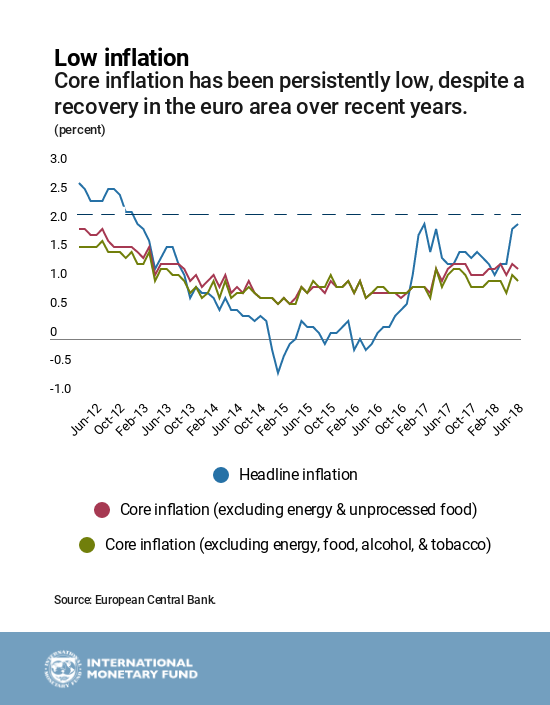

The euro area economy is in its fifth year of recovery, unemployment is close to its pre-crisis level and the output gaps of most countries have closed. Yet, core inflation continues to be low, notwithstanding temporarily high headline inflation due to higher energy prices.

The puzzle

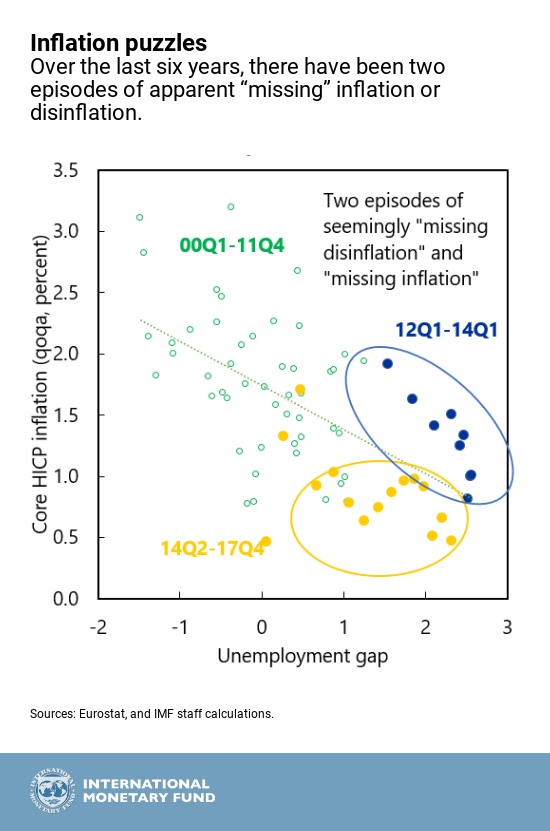

It may look as if the traditional Phillips curve relationship between core inflation and unemployment has broken down over the past five years.

During 2012 to 2014, the euro area experienced a “missing disinflation” episode, where inflation stayed at relatively high levels despite high and increasing unemployment. From 2014 to 2017, there was a “missing inflation” period, with little inflation pressure despite considerable reductions in labor market slack. Some have attributed this to a broken Phillips curve, to difficulties in correctly quantifying slack, or low global inflation.

However, our new study shows that what may seem like an inflation puzzle is nonetheless consistent with a conventional Phillips curve.

The solution

We use a standard version of the Phillips curve, where core inflation depends on inflation—what people expect inflation to be in the future—past inflation, and the unemployment gap.

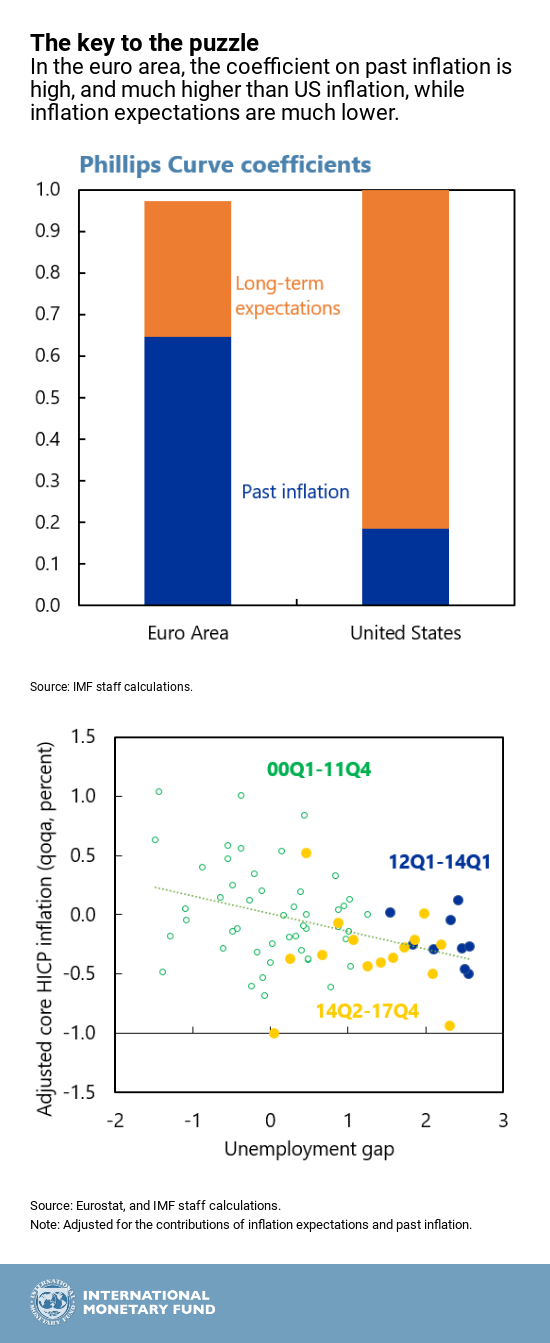

We find that the relationship between core inflation and unemployment is stable, meaning that inflation continues to react to labor market developments. This is true even when considering other measures of slack, such as the output gap, or a broader measure of unemployment that includes those who are underemployed or only marginally attached to the labor force.

What may seem like an inflation puzzle is nonetheless consistent with a conventional Phillips curve.

The key to the puzzle lies in the strong persistence of euro area inflation. In the euro area, the coefficient on past inflation is high, much higher than for US inflation, for example. Similarly, the coefficient on inflation expectations is much lower for the euro area than for the US

What does this mean? It implies that, in the euro area, following a period of weak demand and low inflation, it will take a much longer period of strong demand to get inflation back to the inflation objective. In other words, there is a substantial time lag in the transmission of improving labor market developments to prices. Taking this lag into consideration appears to “solve” the inflation puzzle: core inflation finally aligns with labor market developments.

We also test the alternative hypothesis that low euro area inflation is the result of global low inflation. We do this by including a number of global variables in our Phillips curve, namely the foreign output gap, foreign inflation, non-oil import prices, oil prices, and the nominal effective exchange rate. However, we do not find supporting evidence. Not only are the contributions of global factors to inflation dynamics less important than those of domestic factors, but global factors were also not consistently deflationary in recent years.

What does this mean for monetary policy?

Our findings suggest that convergence of core inflation towards the European Central Bank’s medium-term objective is likely to be gradual. Due to the persistence in the inflation process, a too early withdrawal of monetary accommodation could be a mistake with long-lived consequences.

This conclusion reinforces the case for being “patient, prudent and persistent”. It underlines the importance of the ECB’s commitment to keep policy rates at their current, extraordinary low levels—at least through next summer—and as long as necessary. This will support the slow process of returning inflation to its objective, through both stronger demand and well anchored inflation expectations.