July 16, 2018

Versions in عربي, Baˈhasa indoneˈsia, 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português, Русский

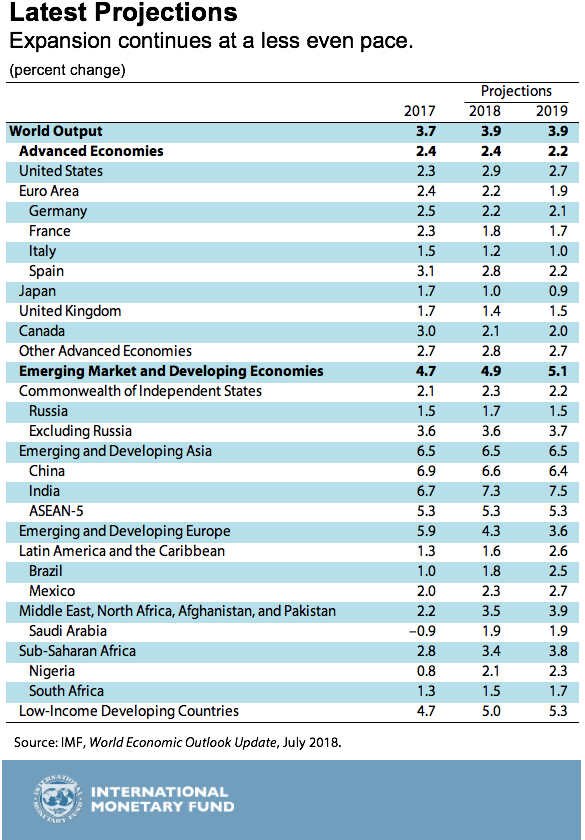

[caption id="attachment_24037" align="alignnone" width="1024"]Amid rising tensions over international trade, the broad global expansion that began roughly two years ago has plateaued and become less balanced. In our latest World Economic Outlook Update, we continue to project global growth rates of just about 3.9 percent for both this year and next, but judge that the risk of worse outcomes has increased, even for the near term.

Growth remains generally strong in advanced economies, but it has slowed in many of them, including countries in the euro area, Japan, and the United Kingdom. In contrast, GDP continues to grow faster than potential and job creation is still robust in the United States, driven in large part by recent tax cuts and increased government spending. Even US growth is projected to decelerate over the next few years, however, as the long cyclical recovery runs its course and the effects of temporary fiscal stimulus wane. For the advanced economies, we project 2018 growth of 2.4 percent, down 0.1 percentage point from our April World Economic Outlook projection. We maintain an unchanged forecast of 2.2 percent growth in those economies for 2019.

For emerging market and developing economies as a group, we still project growth rates of 4.9 percent for 2018 and 5.1 percent for 2019. These aggregate numbers, however, conceal diverse changes in individual country assessments.

The broad global expansion that began roughly two years ago has plateaued and become less balanced.

China continues to grow in line with our earlier projections. In some large economies in Latin America, emerging Europe, and Asia, we now project growth rates below our April forecasts. Supply disruptions and geopolitical tensions have helped raise oil prices, benefiting emerging oil exporters (for example, Russia and Middle Eastern suppliers) but harming importers (for example, India). For the aggregate of emerging market economies, the upward and downward revisions largely offset each other.

Overall growth in sub-Saharan Africa will exceed that of population over the next couple of years, allowing per capita incomes to rise in many countries; but despite some recovery in commodity prices, growth will still fall short of the levels seen during the commodity boom of the 2000s. Adverse developments in Africa—civil strife or weather-related shocks, for example—could intensify outward migration pressures, especially toward Europe.

Fed policy, trade tensions

As always, Federal Reserve policy is central to global financial developments. Given strong US employment and firming inflation, the Fed is on track to continue raising interest rates over the next two years, tightening its monetary policy compared with other advanced economies and strengthening the US dollar. The dollar has already appreciated broadly since April, and financial conditions facing emerging and frontier economies have become somewhat more restrictive. These financial conditions remain relatively benign in historical context despite that tightening, however. Markets—so far—continue to differentiate among borrowers, and capital account pressures have been most intense for those with evident weaknesses (for example, political uncertainty or macroeconomic imbalances). Were the Fed to tighten faster than is currently expected, however, a broader range of countries could feel more intense pressures.

But the risk that current trade tensions escalate further—with adverse effects on confidence, asset prices, and investment—is the greatest near-term threat to global growth. Global current account imbalances are set to widen owing to the United States’ relatively high demand growth, possibly exacerbating frictions. The United States has initiated trade actions affecting a broad group of countries, and faces retaliation or retaliatory threats from China, the European Union, its NAFTA partners, and Japan, among others. Our modeling suggests that if current trade policy threats are realized and business confidence falls as a result, global output could be about 0.5 percent below current projections by 2020. As the focus of global retaliation, the United States finds a relatively high share of its exports taxed in global markets in such a broader trade conflict, and it is therefore especially vulnerable.

Political uncertainty, complacent markets

Other risks have become more prominent since our April assessment. Political uncertainty has risen in Europe, where the European Union faces fundamental political challenges regarding migration policy, fiscal governance, norms concerning the rule of law, and the euro area institutional architecture. The terms of Brexit remain unsettled despite months of negotiation. Prospective political transitions in Latin America over coming months add to the uncertainty. Finally, although some geopolitical dangers may appear to be in remission, their underlying drivers in many cases are still at work.

Financial markets seem broadly complacent in the face of these contingencies, with elevated valuations and compressed spreads in many countries. At the same time, however, high levels of public and private debt create widespread vulnerability. Asset prices are no doubt buoyed, not only by easy financial conditions, but by the generally still satisfactory global growth picture. They therefore are susceptible to sudden re-pricing if growth and expected corporate profits stall. Supporting growth into the medium term—where trend growth rates are forecast to be lower for advanced economies and many commodity exporters—requires that policymakers act now to raise growth potential and resilience through reforms, while re-building fiscal buffers and guiding monetary policy carefully to keep inflation expectations well anchored on targets.

Economic equity, global cooperation

Governments must also pay more attention to economic equity among citizens, and especially protecting the poorest. The widespread political malaise driving many current policy risks, including on the trade front, has roots in several countries’ experiences of non-inclusive growth and structural transformation, heightened by the financial crisis of 2007-09 and the difficulties that followed. It is urgent to address the underlying trends through equity- and growth-friendly policies, while assuring that macroeconomic tools are available to fight the next economic slowdown. Otherwise, the political future will only darken.

While rising to these challenges, countries must resist inward-looking thinking and remember that on a range of problems of common interest, multilateral cooperation is vital. Issues of common concern—where national action is not enough—include strengthening the multilateral trading system, reducing excess global imbalances, financial stability policy, international tax policy, cyber and other terrorist threats, disease control, and global warming. A truly global effort is also needed to curtail corruption, which undermines faith in government in so many countries. Finally, recurrent surges in international migration pressures, which have proven so politically destabilizing recently, cannot be avoided without cooperative action to improve international security, support the Sustainable Development Goals, and resist climate change and its effects.