March 21, 2018

Version in 日本語 (Japanese), Português (Portuguese)

[caption id="attachment_22971" align="alignnone" width="1024"] New study finds that all types of recessions lead to permanent losses in output and welfare (photo: Peshkov/iStock by GettyImages).[/caption]

New study finds that all types of recessions lead to permanent losses in output and welfare (photo: Peshkov/iStock by GettyImages).[/caption]

Economic recessions are typically described as short-term periods of negative economic growth. According to the traditional business cycle view, output moves up and down around its long-term upward trend and after a recession, it recovers to its pre-recession trend. Our new study casts doubt on this traditional view and shows that all types of recessions—including those arising from external shocks and small domestic macroeconomic policy mistakes—lead to permanent losses in output and welfare.

Nearly a decade after the global financial crisis erupted into the Great Recession, the global economy finally appears to be on the verge of strong growth . Until recently, however, economic growth fell below forecasts of a vigorous rebound, as predicted by supporters of the traditional business cycle theory.

Some researchers have explained the sluggish post-crisis growth as driven by demographic trends or other factors specific to the United States. But such explanation ignores the fact that output dynamics after the crisis followed a similar pattern seen in other countries.

In a 2008 paper , we had shown for a sample of 190 countries that financial and political crises have permanent long-run economic costs in terms of output forgone. On average, the magnitude of the persistent loss in output is about 5 percent for balance of payments crises, 10 percent for banking crises, and 15 percent for twin crises.

Using updated data from 1974 to 2012, we confirm our earlier findings that the irreparable damage to output is not limited to financial and political crises. All types of recessions, on average, lead to permanent output losses. Contrary to conventional wisdom, we also show that countries do not typically have growth booms before crises and recessions.

Challenging the traditional view

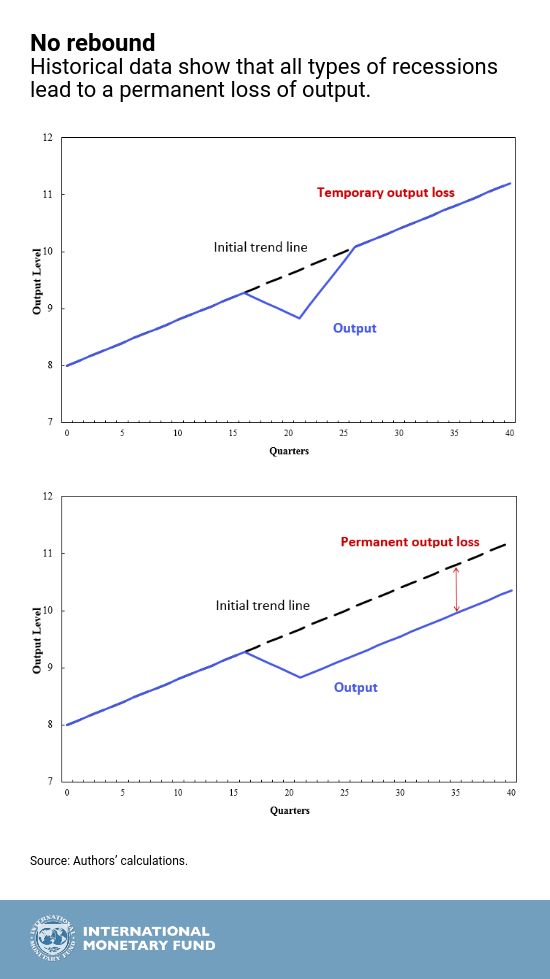

In the traditional view of the business cycle, a recession consists of a temporary decline in output below its trend line, but a fast rebound of output back to its initial upward trend line during the recovery phase (see chart, top panel). In contrast, our evidence suggests that a recovery consists only of a return of growth to its long-term expansion rate—without a high-growth rebound back to the initial trend (see chart, bottom panel). In other words, recessions can cause permanent economic scarring.

Economic development

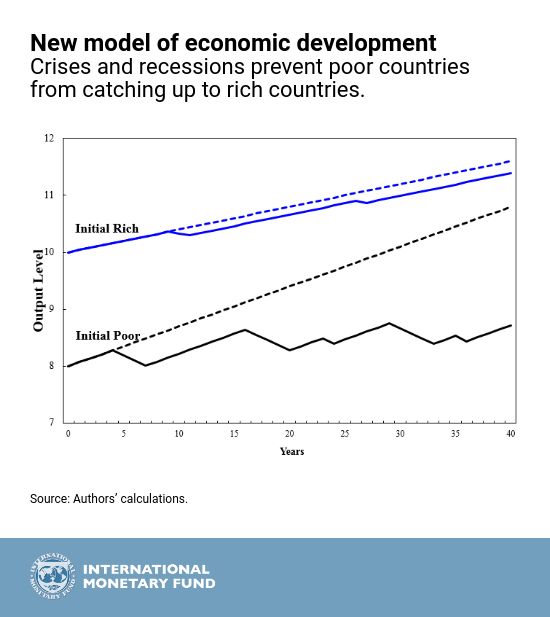

These economic scars from recessions and crises also have dramatic long-term consequences. According to traditional theory, poor countries should catch up to income levels of rich countries (see dotted lines in chart below) because they should have a bigger bang for each buck of investment. But the historical evidence contradicts this theory. Instead, poor countries’ incomes have fallen further behind. Our new model explains a key reason why. Poor countries suffer deeper and more frequent recessions and crises, each time suffering permanent output losses and losing ground (solid lines in chart below).

Revisiting the output gap

What does this new model of the business cycle mean for economic policy?

For one, the concept and measurement of the output gap may need to be revisited to help policymakers get an accurate reading of the economy.

Potential output is conceived as the long-term trend in output, with the “output gap” reflecting the deviation of actual output from potential output or the position in the “cycle.” But conceptually, if shocks to growth lead to permanent shifts in the trend of output, then there is no difference between actual and potential output, and therefore no business “cycle” to speak of.

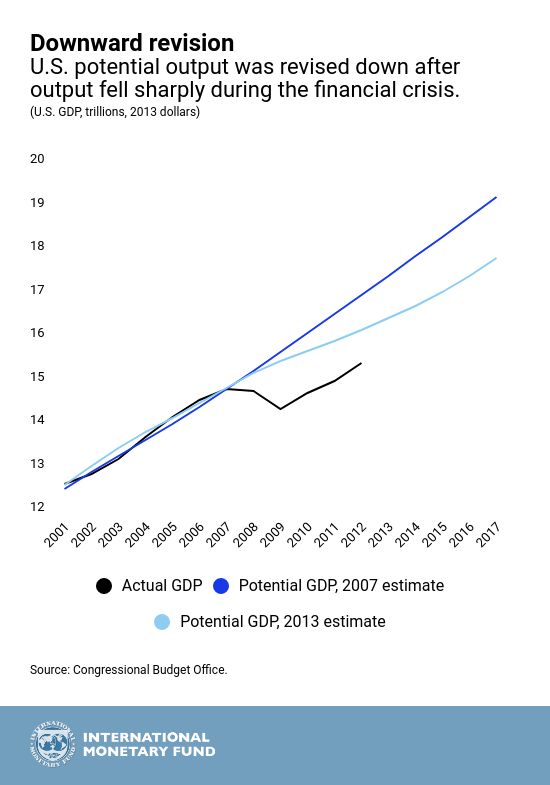

Estimating potential output by smoothing the path of actual output creates false cycles and constant revisions in potential output estimates. For instance, there has been a constant downward revision in the estimated path of potential output for the United States and a closing of the output gap in recent years. But potential GDP estimates were revised down to actual GDP, not the other way around.

Such revisions and closures of output gaps are partly just a result of measurement issues. When including years of lower output after the crisis, potential GDP (the measured trend) is mechanically reduced, with a corresponding dramatic change in our view of history. We now measure a very positive output gap (when actual output is above potential) for most advanced countries on the brink of the crisis in 2007, even though there were no signs of overheating at the time.

Prevention and response to crises and recessions

The new business cycle model suggests that we need to be more conservative in forecasting growth after recessions. We also need to avoid using output gap measures that are misleading and inconsistent over time.

Economic policies should be geared toward avoiding crises and severe recessions and responding with appropriate stimulus and safety nets. Sustainable economic policies and financial regulation that contains excessive risk-taking are the first best options. If these policies are insufficient, central banks will need to include financial stability risks in their analysis and decisions. Foreign exchange reserves can also help insure against losses due to external shocks.