November 21, 2017

Versions in 中文(Chinese), 日本語 (Japanese)

[caption id="attachment_21948" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A Japanese mother works at home with her child. Encouraging women to take on full time work and have children would help boost growth in Japan (photo: iStock by Getty Images).[/caption]

A Japanese mother works at home with her child. Encouraging women to take on full time work and have children would help boost growth in Japan (photo: iStock by Getty Images).[/caption]

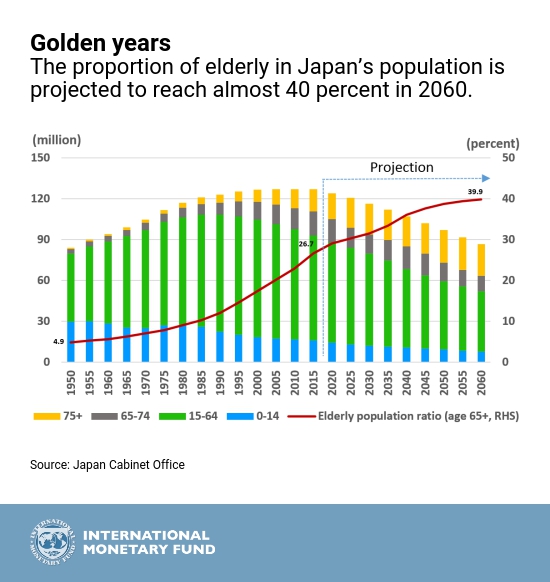

Problem: Japan is the most aged society among advanced economies (almost 27 percent of its people are over 65). It also faces a shortage of labor (unemployment is just 2.8 percent). Both limit the country’s growth potential.

Solution: Encourage women to take on more full time work and have children.

But is it possible to reconcile these two seemingly contradictory goals? The answer is yes, based on evidence from Scandinavia and research by IMF economists such as Naoko Miake, Kalpana Kochar, and Yuko Kinoshita.

In Japan, the tax code, social norms and corporate labor practices all have some elements that discourage childbearing.

While Japanese men have traditionally enjoyed lifetime employment, the same isn’t true for women. More than half of Japanese women with jobs choose part-time or temporary work, largely to balance the demands of child care, elder care and housework. The choice also reflects frequent demands for overtime (often underpaid or unpaid) in regular employment, a phenomenon that has led to cases of “karoshi,” or death from overwork. Part-time workers earn about half that of full timers, which has helped limit wage gains despite low unemployment.

Wage scales are based in part on the number of dependents in the household, on the assumption that the husband is the sole breadwinner. And many women also choose part time work to stay under the minimum income levels that are subject to tax.

What can be done to increase fertility and ease the labor shortage? Reforming the tax code to eliminate disincentives to full time work would be a good place to start. Providing more child-care facilities would also help.

But these steps alone won’t be enough. Deeper changes are needed in social norms that discourage professional women from having families. Limiting overtime hours would give men more time to share in housekeeping and childrearing duties, while encouraging mothers to keep their jobs. And studies suggest that couples have a better chance of having a second child if the man spends more time at home.

Japan needs to act fast if wants to keep its population from shrinking further: after 2018, the number of women of reproductive age will decline sharply. Japan’s total population is expected to drop between now and 2025 by almost 4 million—roughly the population of Los Angeles—and to decline even faster beyond that.