September 20, 2017

Versions in Español (Spanish), 日本語 (Japanese), Русский (Russian)

[caption id="attachment_21279" align="alignnone" width="1024"] People lining up in front of a charity house in São Paulo, Brazil: Over 200 million people around the world are unemployed, despite overall economic growth (photo: Paulo Whitaker/Reuters/Newscom)[/caption]

People lining up in front of a charity house in São Paulo, Brazil: Over 200 million people around the world are unemployed, despite overall economic growth (photo: Paulo Whitaker/Reuters/Newscom)[/caption]

Economic growth provides the basis for overcoming poverty and lifting living standards. But for growth to be sustained and inclusive, its benefits must reach all people.

While strong economic growth is necessary for economic development, it is not always sufficient.

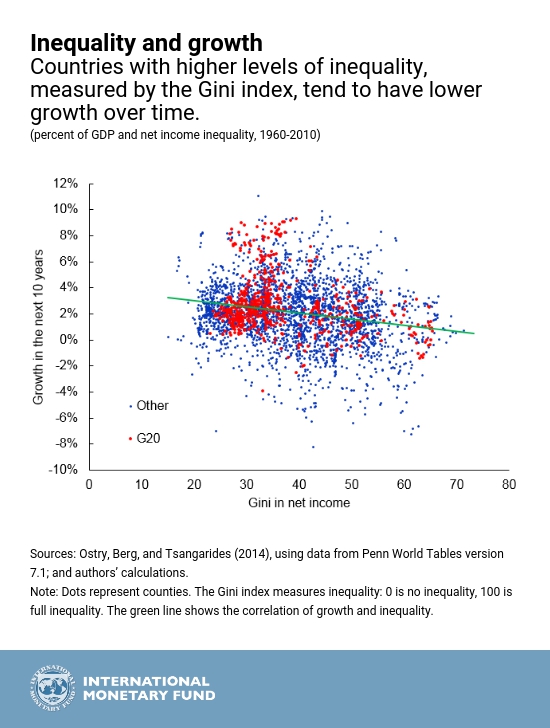

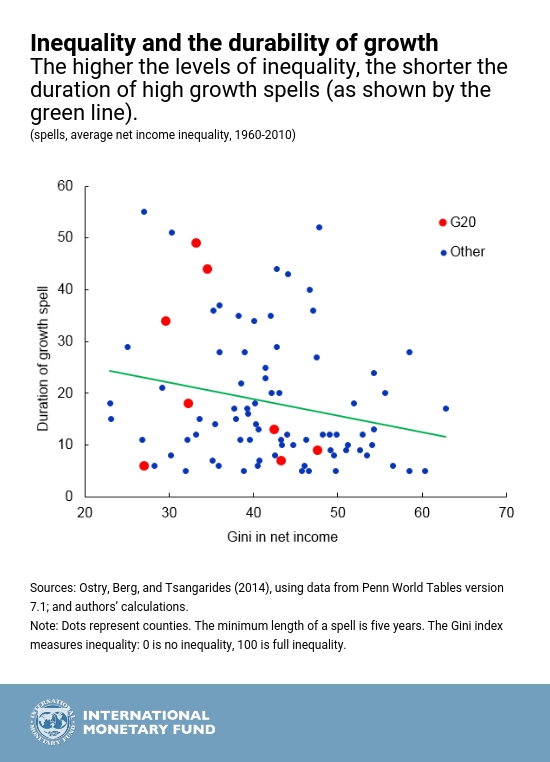

Over the past few decades, growth has raised living standards and provided job opportunities, lifting millions out of extreme poverty. But, we have also seen a flip side. Inequality has risen in several advanced economies and remains stubbornly high in many that are still developing. This worries policymakers everywhere for good reason. Research at the IMF and elsewhere makes it clear that persistent lack of inclusion—defined as broadly shared benefits and opportunities for economic growth—can fray social cohesion and undermine the sustainability of growth itself.

We synthesize the lessons from our work with countries, and our research on policy options to mitigate growth-equality tradeoffs and to foster inclusive growth in a note for the meeting of the G20 leaders in Hamburg, Germany, this past July.

A few facts

Lack of inclusion results in both unequal outcomes and unequal opportunities. Income inequality—the most widely cited measure of inequality of outcomes—has been declining, when the world is considered. The decline is due in large part to strong growth in many emerging market and developing economies, although two-thirds of global inequality is still attributable to differences in average income between countries.

However, if the countries are considered individually, income inequality rose sharply in many places. In the most advanced economies, the bulk of the gap opened from the 1990s until the mid-2000s. In emerging market and developing economies, inequality is still high, even though it declined in recent decades in many of them.

Lack of inclusion also manifests itself in unequal access to jobs and basic services, such as health and education. To cite just a few examples: over 200 million people around the world are unemployed, with youth unemployment at alarming levels in many countries. Mortality rates for some segments of the population are increasing, including in the United States.

Twenty percent of adults in advanced economies remain excluded from formal access to finance: for example, they do not have an account with a financial institution. Finally, wide-spread gender discrimination has led to persistent differences in health, education and incomes between men and women in large parts of the world.

Technology and economic integration have brought large benefits to many economies, but the benefits have not always been broadly shared. Both technology and trade have been driving forces behind growth and productivity, and lowered prices, greatly benefitting the poor who spend a large share of their incomes on food, clothing, and other basic goods.

However, technology has increased the demand almost exclusively for skilled labor, while trade has sometimes displaced lower-skilled workers. Greater integration of economies has also resulted in relocation of factories and greater use of equipment, displacing workers.

There are options to encourage growth for all

So, what can be done to foster inclusive growth?

The answer is not to hold off on reforms that boost productivity and growth but rather to focus on policies that offer opportunities for all. Policymakers must design measures that can mitigate potential compromises between the objectives of raising growth and reducing inequality.

Several options are available to accomplish this.

For example, more—and more efficient—spending on roads, airports, power grids and education can create jobs and boost economic growth. Broadening access to financial services—combined with measures to ensure financial stability—gives more people and firms the opportunity to consume and invest, as happened recently in India, Mexico, or Rwanda.

Assistance with job search and job matching as well as training programs can help the jobless to find work that matches their skills—countries such as Finland and Germany, where the participation in such programs is the highest among European Union countries, have the lowest long-term unemployment rates. Better property rights that boost security to individuals encourages labor mobility, discourages informal work, and supports inclusive growth.

Fiscal policy is a powerful instrument for ensuring inclusive growth and has played a key role in addressing inequality. For example, closing the outcome gaps in education and health between advantaged and disadvantaged groups can reduce inequality and promote growth; social benefits, such as cash transfers can help protect the most vulnerable; and revenue mobilization raises the needed financing for social spending and may also contribute to lowering inequality. Design matters so that the fiscal policy mix can best balance equality and efficiency.

For trade and technology, domestic policies go a long way in translating strong growth to growth that is also inclusive. Indeed, previous IMF studies have shown the importance of how governments design their policies: for example, measures that encourage foreign trade boost growth, but can increase inequality if they displace low-skilled workers in the process. In contrast, attendant reforms, such as accessible education, targeted to raise income and productivity of low-skilled workers, can boost growth while reducing inequality.

Extending the fruits of growth to the widest possible group of people is not easy and clearly requires a global effort as recognized by the G20. But it is not impossible. The IMF will continue to work with policymakers around the world—through research, technical assistance and surveillance work—to help achieve this goal.