July 28, 2017

[caption id="attachment_20796" align="alignnone" width="4368"] Since 2013, global imbalances have become increasingly concentrated in advanced economies. Surplus and deficit countries alike bear responsibility for correcting excess external imbalances (photo: Caro Oberhaeuser/Newscom)[/caption]

Since 2013, global imbalances have become increasingly concentrated in advanced economies. Surplus and deficit countries alike bear responsibility for correcting excess external imbalances (photo: Caro Oberhaeuser/Newscom)[/caption]

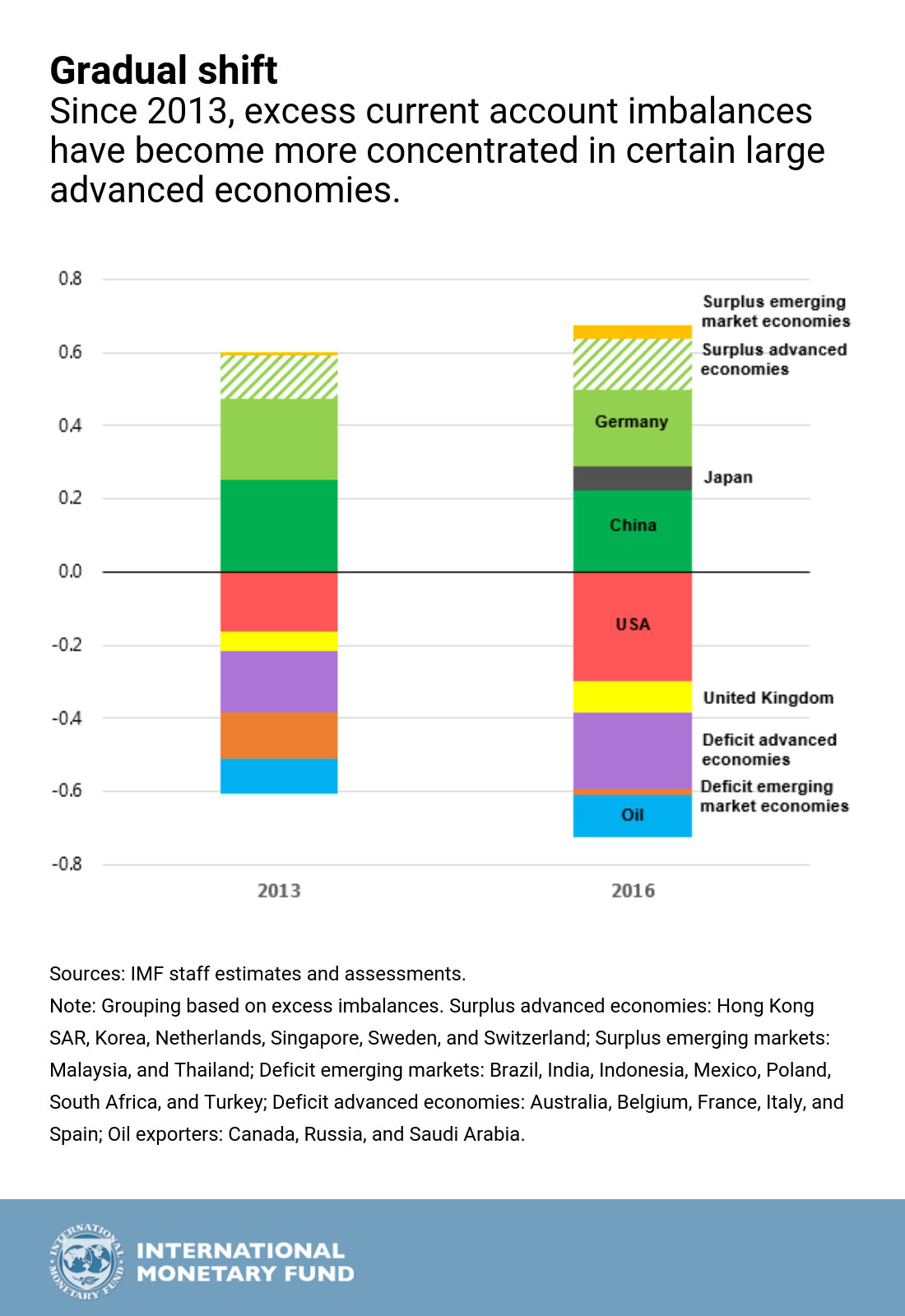

We have just released our latest assessments of external positions for the 29 largest economies. As discussed in this year’s External Sector Report, excess current account imbalances—that is, those beyond the levels warranted by country fundamentals—were broadly unchanged in 2016. They represented about one-third of total actual surpluses and deficits, with only small shifts in 2016.

Since 2013, however, there has been a rotation of these excess imbalances toward advanced economies, posing new risks and policy challenges.

On the bright side, excess imbalances narrowed in key emerging market economies, led by a smaller excess surplus in China and smaller excess deficits in others key economies (such as Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey), where policies supported external adjustment as prospects of U.S. monetary policy normalization became more evident and external financing conditions tightened.

But this has been accompanied by a widening of excess imbalances in several advanced economies and the continuation of large and persistent excess surpluses in others (e.g., Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, Singapore, and Sweden), an issue that we explore in detail in the report. Our historical analysis suggests that these large and persistent surpluses, outside oil-exporting countries and financial centers, are a fairly recent phenomenon and in the few cases where they reversed, policy actions on multiple fronts played a role.

What do these developments mean for economic policy?

The current constellation of excess imbalances—especially the persistent surpluses in the same group of countries and the resurgence of deficits in key debtor economies—indicate that automatic adjustment mechanisms are weak. That is, prices and saving and investment decisions are not adjusting fast enough to correct these excess imbalances. This partly reflects rigid currency arrangements but also structural features (like inadequate social safety nets and barriers to investment) which lead to undesirable levels of saving and investment in some economies. This calls for more forceful policy action.

While the increased concentration of excess deficits in advanced economies—mainly the United States and United Kingdom—could reduce deficit-financing risks in the near term, it could pose other downside risks if unaddressed, especially over the medium term. The concentration of deficits in a few countries raises the likelihood of protectionist measures. And the continued reliance on demand from debtor countries risks derailing the global recovery, while raising the chances of a disruptive adjustment down the road.

Given these risks, addressing external imbalances in a way that is supportive of global growth is a shared responsibility. It requires a recalibration of the policy mix in deficit and surplus economies alike.

What can be done

As a general rule, excess deficit countries should move forward with fiscal consolidation, while gradually normalizing monetary policy in tandem with inflation developments. Excess surplus economies who have room in their budgets should reduce their reliance on easy monetary policy and allow for greater fiscal stimulus. Where monetary policy is constrained from playing a role, as is the case with individual euro area members, countries should look to fiscal and structural policies to facilitate relative price adjustments. Exchange rates should continue to be allowed to move in line with fundamental levels and interventions should be limited to addressing disorderly market conditions, as has been generally the case in recent years for most countries.

Moreover, countries should increasingly emphasize structural policies. Excess surplus countries should focus on lifting distortions that constrain domestic demand or limit trade competition. In excess deficit economies, policies should be directed to improving external competitiveness and overall saving, with particular emphasis given to reforms that boost education outcomes and strengthen the business climate.

Finally, our view is that protectionist policies should be avoided, as they are unlikely to meaningfully address external imbalances but they would be detrimental to both domestic and global growth.

Why we do this

Assessing countries’ external positions is a core mandate of the IMF. These assessments are an analytical tool to determine on a multilaterally-consistent basis the difficult—and often contentious—issue of when external imbalances are appropriate or when they signal risks. In fact, imbalances are often healthy and desirable—developing economies, who need to invest to catch up with living standards elsewhere, should generally run deficits, while others that are aging quickly, like Japan and Germany, need to run surpluses to meet related obligations in the future. Our focus, therefore, is on identifying the undesirable portion and on discussing policies to address them.

The exercise is meant to avoid a tragedy of commons, where countries acting independently and in their own self-interest undermine the common good of supporting global growth and stability