Versions in Français (French), and Português (Portuguese)

Migration of sub-Saharan Africans is growing rapidly. Just like the region’s population, the number of migrants doubled since 1990 to reach about 20 million in 2013. In the coming decades, migration will expand given the demographic boom in the working-age population—the group that typically feeds migration. We studied these trends in a recent paper because both receiving and sending countries need the right policies so all can benefit.

People on the go

Two trends dominate the evolution of sub-Saharan migration.

The number of refugees—people fleeing due to war or persecution—has decreased considerably since 1990, both within and outside the region. In 1990 about half of total migrants were refugees, and this share has declined to only about 10 percent by 2013.

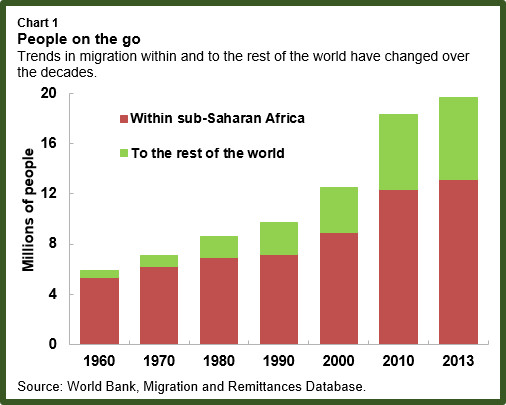

At the same time, the share of migrants that move outside the region for economic reasons has increased steadily, growing sixfold between 1990 and 2013—from about 1 million to 6 million. In comparison, economic migrants within the region increased threefold—from 4 million to 12 million (Chart 1).

Migration within Africa is predominantly driven by geographic proximity, income differences, wars in the home country, and relative political stability in the host country, along with cultural links and environmental factors such as droughts or floods. Cote d’Ivoire and South Africa are among the biggest recipients of migrants from the region.

Migration to the rest of the world is driven mainly by the search for better economic opportunities, and the primary destinations are advanced economies. About 85 percent of the sub-Saharan African diaspora in the rest of the world is in countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—with the United States, the United Kingdom, and France hosting about 50 percent of sub-Saharan African migrants.

Evolving demographics, evolving migration

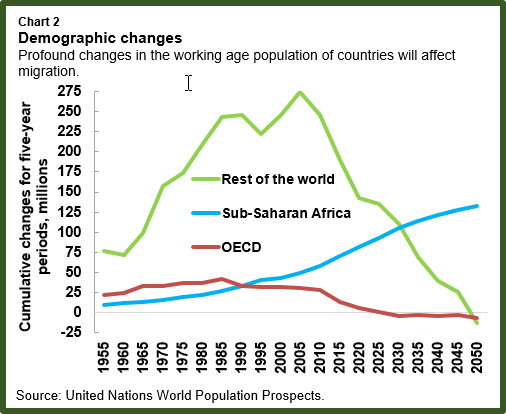

There is an ongoing profound demographic transition in the region that will further shape migration from sub-Saharan Africa. The population of the region will not only continue to increase rapidly—from about 900 million in 2013 to 2 billion in 2050—but also the working-age population, the group that typically feeds migration, is set to increase even more rapidly—from about 480 million in 2013 to 1.3 billion in 2050 (Chart 2).

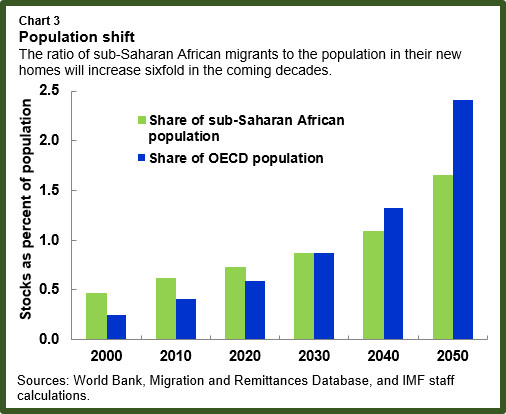

As a result of these demographic trends and the persistence of large differences in income between sub-Saharan African countries and advanced countries, migration will likely increase. Our projections suggest that the ratio of sub-Saharan African migrants to the population of their new homes in OECD countries will increase sixfold in the coming decades, from about 0.4 percent in 2010 to 2.4 percent by 2050. This large increase would be the result of the expansion of migration from the region combined with the very slow population growth expected in the OECD (Chart 3).

Trends require better policies

Migrant workers can have a positive impact on growth in receiving countries, in particular those where the population is aging rapidly. They also bring additional tax revenues and much needed social contributions in their new home countries to support retired workers. At the same time, the flows of remittances sent back to their countries of origin will continue to support the living standards of relatives. This, in turn, helps alleviate poverty, and will continue to play an important role for the economy as a whole as a stable source of foreign earnings.

Our colleagues recently wrote a blog about the benefits that migrants bring to advanced economies, which tells the story from another angle.

Since migration both within and outside the region will likely continue to expand in the coming decades, countries will need to design policies that facilitate the rapid social and economic integration of migrant workers for all to benefit.

The boost to the labor force should somewhat compensate for aging and declining domestic populations in rich countries, which is good for both economic growth and taxes in the long run. Very importantly, this should minimize social tensions often associated with immigration emanating from concerns about the displacement of native workers and fiscal costs.