The remarkable collapse in the price of oil—a key global price that has virtually halved in the space of just a few months—has received a lot of attention lately.

The remarkable collapse in the price of oil—a key global price that has virtually halved in the space of just a few months—has received a lot of attention lately.

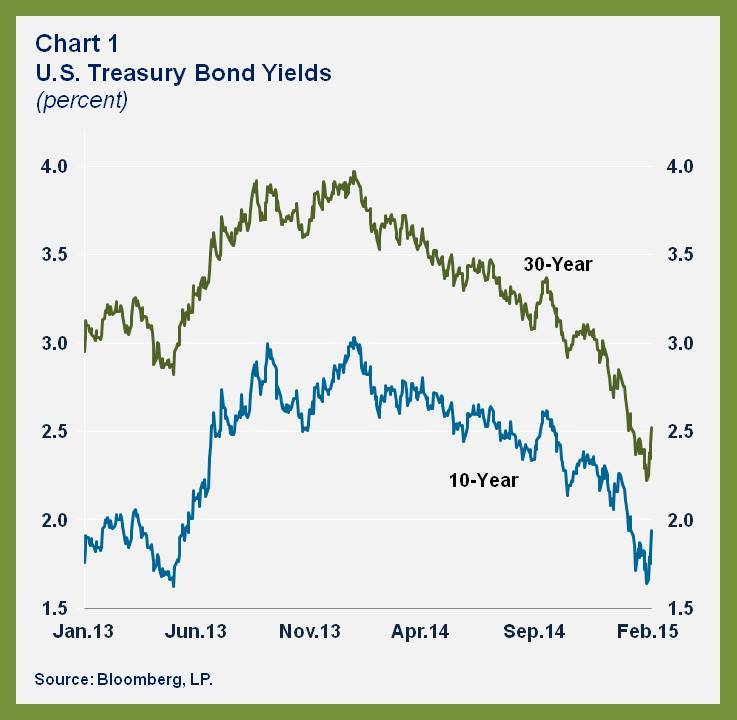

Meanwhile, another significant shift has taken place in recent months that is just as surprising and has wide-reaching global implications—the dramatic drop in long-term U.S. Treasury bond yields. The last time we saw 10-year Treasury bond yields this low was in early May 2013. As many will remember, this didn’t last long and when it corrected, it set off a burst of volatility across emerging markets.

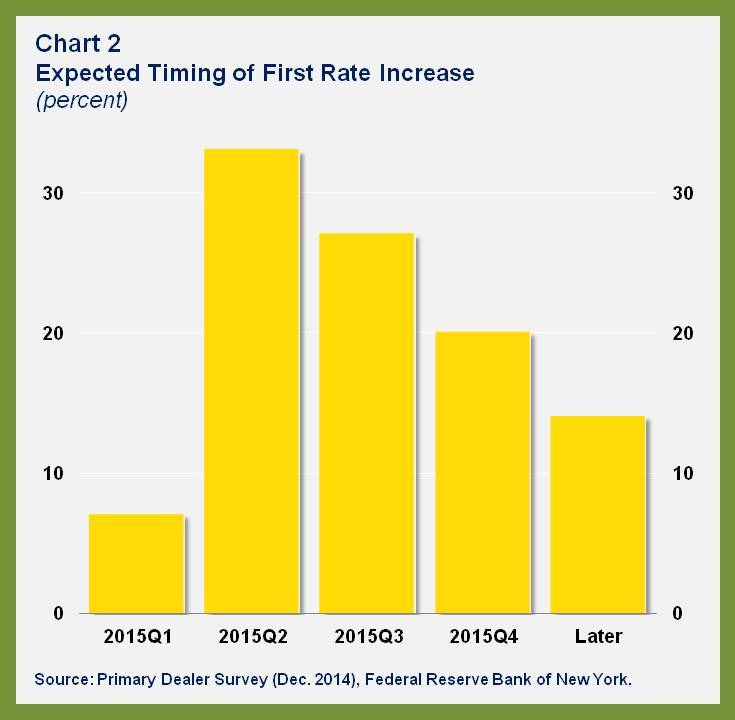

The sharp drop in this key global interest rate has occurred despite the general strength of the U.S. economy, the positive news coming from recent data, and the broad consensus among analysts that the day is soon approaching when the Federal Reserve will start raising interest rates.

A term premium story

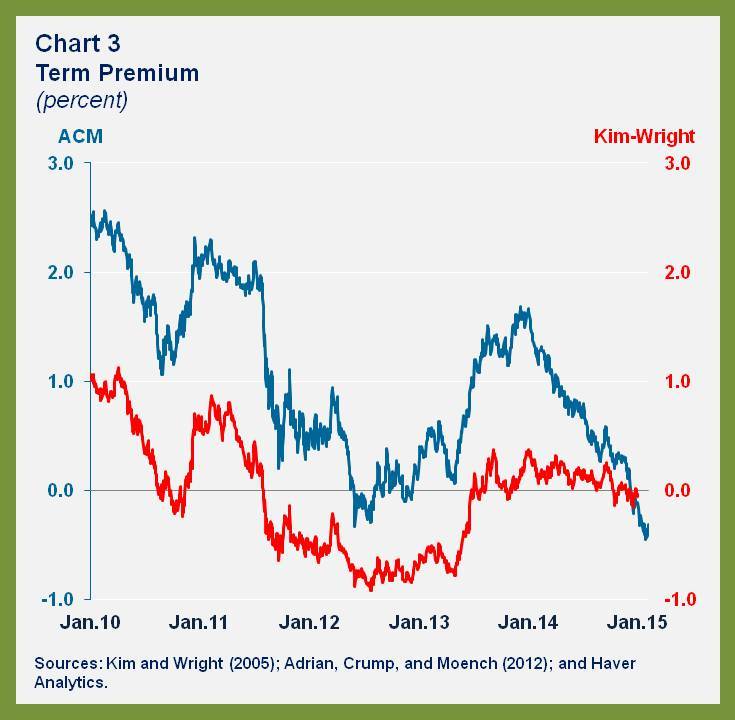

Once you strip out changes in the expected path of future short term rates, it becomes clear that it is the term premium—the compensation that investors require for holding a long-term bond rather than rolling over a sequence of short-term bonds—that has been responsible for a big chunk of the fall in Treasury rates. The term premium has actually turned negative since the start of the year. Looking back in history, this is a rather abnormal occurrence.

So what is going on?

While likely reflecting a combination of factors, there are a number of candidate explanations:

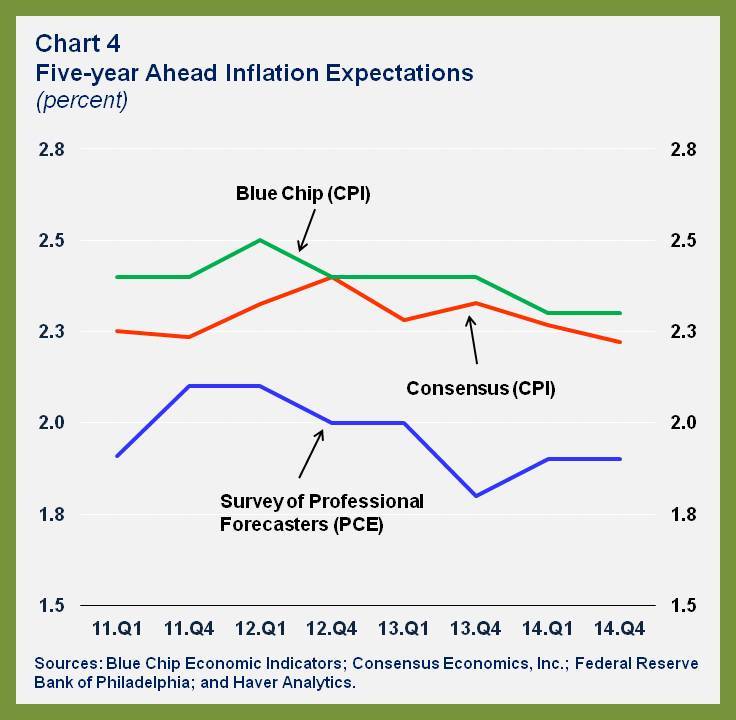

- The disinflation vortex. Some believe that long-run inflation in the United States could become permanently stuck below the Fed’s goal of 2 percent. As a consequence, holders of longer maturity bonds would need less compensation for future inflation. Certainly, market pricing of inflation breakevens has been falling, something that has been highlighted by the FOMC in recent statements. However, we have our doubts whether expectations of falling inflation are a big part of the story. Survey data seem to show that inflation expectations have not moved much.

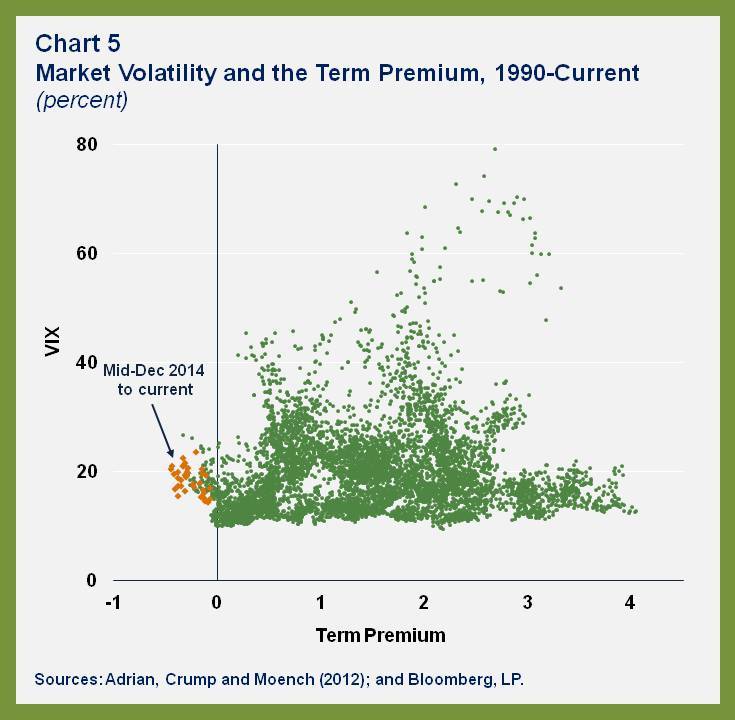

- Fear over greed. Increasing global risk aversion is another possibility. With events in Ukraine, Greece, and the Middle East, investors have decided to take risk off the table and are heading to the gold standard of safe assets: U.S. Treasuries. While this is likely part of the story, the current unusually low levels of Treasury yields still seem incongruent with the market pricing of volatility.

- A scarcity of safe assets. The recent improving fiscal positions in some of the large industrial countries, including the United States, has reduced the net supply of global safe assets. At the same time, the largest central banks (in the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the euro area) have either bought or are intending to buy a significant share of their outstanding sovereign bonds. This implies a diminishing stock of safe assets left for private investors, pushing up bond prices and lowering U.S. yields (along with yields in many other industrial countries).

- Still better than the rest. Although yields on U.S. Treasuries have been falling, they are still a cut above what you might earn elsewhere. German and Japanese 10-year yields are only 0.3 percent. When looked at from this perspective, and adjusting for sovereign risk, even the shrinking returns on U.S. government bonds do not look too bad.

- The strong dollar. The recent stellar U.S. growth performance is diverging from much of the rest of the world. It is not surprising, then, that investors would expect the dollar to continue to strengthen in the months ahead. Indeed, Secretary Lew recently reinforced that view by saying “I have been consistent in saying, as my predecessors have said, that a strong dollar is good for the United States.” The yield differential mentioned above combined with the expected appreciation should mean continued flows into U.S. dollar assets which, in turn, will put downward pressure on the whole U.S. yield curve.

Risk yes, conundrum no

Some have argued that the falling long-term rates are set to thwart the Fed’s ability to control financial conditions and guide the economy to full employment and stable prices—a so-called “Yellen conundrum.”

We don’t buy this.

Far from being a conundrum, having long-term rates at relatively low levels may actually give the Fed more degrees of freedom. The Fed can steadily raise policy rates and, even if long-term rates remain lower than expected, this will still act as a brake on the economy through the effects on the exchange rate, interest rates on credit cards and floating rate loans, or equity prices. However, at the same time, if long-term rates stay lower this will help support the housing sector, the largest piece that has yet to fall into place in the jigsaw of the U.S. recovery.

If inflation pressures were to become more prominent—which we currently see as unlikely—the yield curve should steepen automatically to act as an additional countervailing force. If somehow Treasury yields remain unusually low, though, the Fed could easily raise policy rates at a faster pace, returning to neutral on a more accelerated timetable. Doing so would have the added benefit of helping to mitigate potential financial stability risks that arise from ultra-low policy rates.

Rather than being concerned right now about a possible monetary policy conundrum, what we should be wary of, instead, is a rapid unwinding of the falling term premium. We saw this in 2013 as the Fed shifted closer toward tapering its bond purchase program and markets reacted. Long-term rates shot up 100 basis points in a matter of weeks. As a result, mortgage activity experienced a sudden stop, residential investment stalled, and the negative consequences spilled out into the global economy, particularly to emerging markets.

At this point it is far from clear what may precipitate such a sharp increase in U.S. bond yields. Better data could certainly do the trick—we got a taste of that on Friday when the Bureau of Labor Statistics released a gangbuster jobs report and yields have already moved off their recent lows. Certainly continued effective communication by the Fed will be needed so as to avoid surprising the market.

Even then though, we may find that the recent low Treasury rates could prove to be all too temporary. In the months ahead, we may look back on this time with hindsight as a period where long-term rates transitorily overshot their fundamentals.

Rather than attaching a warning sign to the conundrum of falling yields, what we should be watching out for is the economic and financial stability fallout that could unfold if U.S. yields snap back upwards in a sudden and unexpected manner.