(Version in Français and Español)

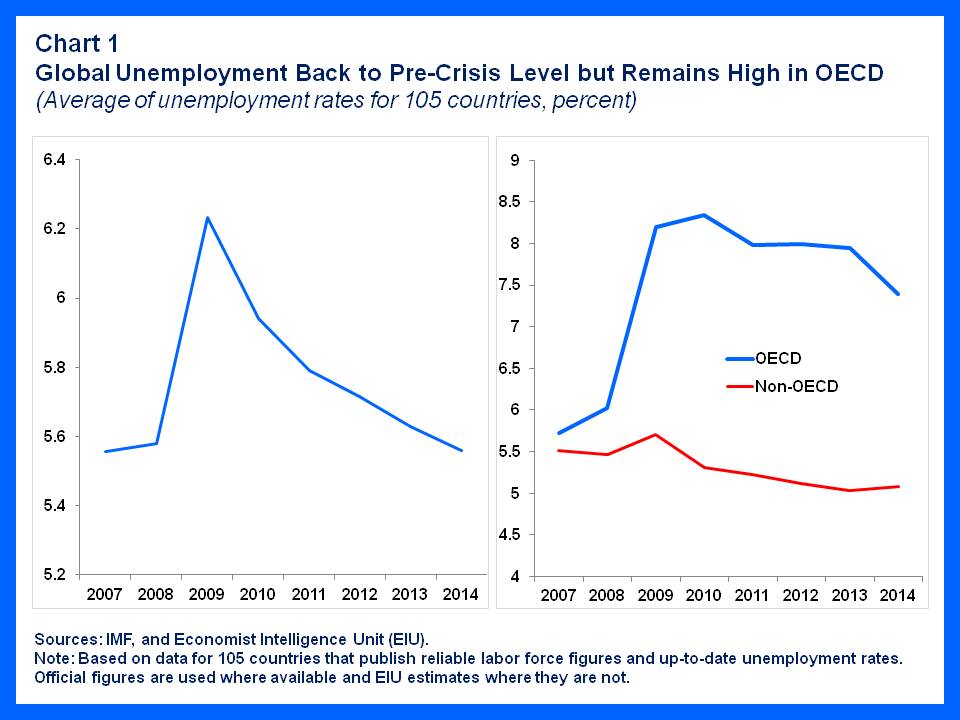

Seven years after the onset of the Great Recession, the global unemployment rate has returned to its pre-crisis level: the jobless rate fell to 5.6% in 2014; essentially the same as in 2007, the year before the recession (chart 1, left panel).

The fall is good news but it is too soon to say “mission accomplished.” Among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average jobless rate is still well above the pre-recession level, in sharp contrast to that in non-member countries (chart 1, right panel).

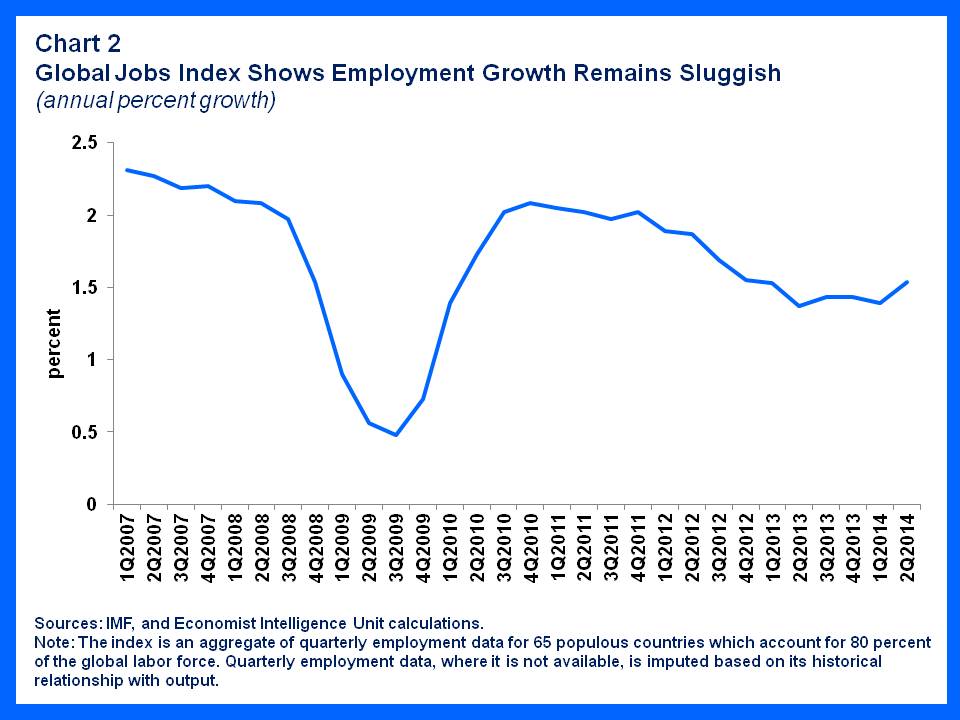

Moreover, a new Global Jobs Index shows that global employment growth remains sluggish at about 1.5% a year, considerably lower than the annual rates of 2-2 ½ percent employment growth that prevailed before the crisis (chart 2).

The index makes quarterly estimates of employment levels in 64 large economies and aggregates them into a global total. The countries covered represent about 95% of global GDP and 80% of the global labor force. For countries where quarterly employment data are not available, the employment levels are derived by estimating historical relationships between jobs and growth.

The index does show that global employment has grown by about 9 percent—which translates into 208 million jobs being created—since the low point of the recession. So things have gotten better, but the pace of job creation has not returned to what prevailed before the crisis.

The index can be used to take the pulse of global labor markets at more regular intervals than has been done before. While financial markets are monitored second-by-second, data on jobs—which matters more to most people—are often not available every quarter because many countries do not report employment numbers in a timely manner.

Jobs and growth: can’t have one without the other

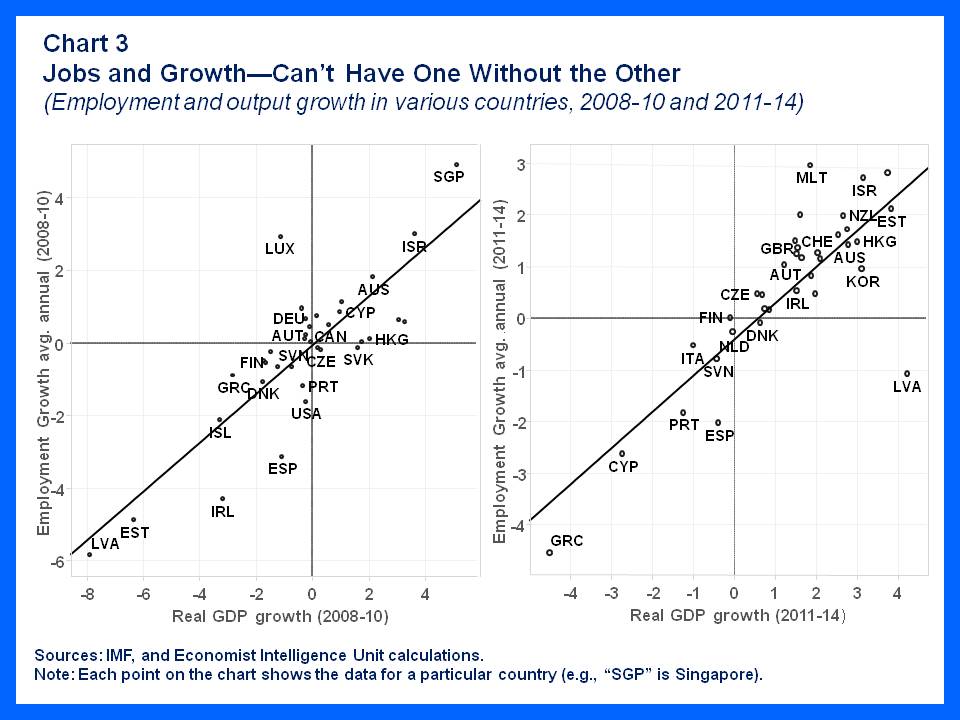

The construction of the index gets around a problem—the lack of timely employment data—by relying on the fact that job creation generally tracks overall growth in the economy. For both OECD and non-OECD countries, the relationship between jobs and growth has held up well over the Great Recession.

The left panel of chart 3 shows the strong link between employment and output growth during the Great Recession years from 2008 through 2010. In countries where the economy grew ( such as Singapore, Israel and Australia, shown in the northeast quadrant), employment grew as well. Where output declined (such as in Spain and Ireland, shown in the southwest quadrant), employment fell as well.

A similar relationship has prevailed during the uneven global recovery from 2011 through today. Countries where growth has recovered have seen employment increase as well. The U.S. economy, for example, grew at an annual rate of nearly 5% in the two middle quarters of 2014, its fastest six-month pace in more than a decade. As a consequence, U.S. employers hired nearly 3 million additional workers in 2014, the most in 15 years.

In some European countries, real GDP continued to fall during 2010-14 and employment did as well. As a consequence, unemployment there remains alarmingly high—around 25% in Greece and Spain, more than 14% in Portugal and 11.5% in the euro area as a whole. The youth unemployment rate stood at an unprecedented rate of 23 percent in the euro area in mid-2014.

More work to do

It is too soon to say if the global economy is settling into a slower pace of employment growth. Certainly, very weak jobs growth in the European Union, which represents nearly 25% of global GDP, is a factor. So too is slower economic growth in China, where the pace of GDP expansion has slowed from more than 10% in the middle of the last decade ago to around 7% now—indeed the slower rate of growth in China is one of the main reasons for the weakening of the Global Jobs Index in the last 18 months.

Countries need a mix of policies to stimulate both aggregate demand and supply to raise employment growth, as discussed in an earlier post.

Broadly speaking, in advanced economies, monetary policy should continue to support the recovery in demand and policies to reduce public debt must be as growth-friendly as possible.

Emerging markets, where growth is slowing from pre-crisis rates, need to primarily address underlying structural problems, which vary from removing bottlenecks in the power sector to reforms of labor and product markets. In many countries, there is a strong case for increasing public investment in infrastructure, which would provide a boost to demand in the short term and to supply (i.e. potential output) over the longer term.

In short, the fall in global unemployment is welcome news, but there is more to do to boost growth, which in turn will help absorb the expanding global labor force into jobs.