(Version in Español Français, Русский, 中文, and 日本語)

We’ve had a spate of good news on the economic front recently. Does this mean that we are finally out of the fiscal woods? According to our most recent Fiscal Monitor report, not yet, as public debt remains high and the recovery uneven.

First, the good news. The average deficit in advanced economies has halved since the 2009 peak. The average debt ratio is stabilizing. Growth is strengthening in the United States and making a comeback in the euro area, and should benefit from the slower pace of consolidation this year. Emerging markets and developing countries have maintained their resilience, in part thanks to the policy buffers accumulated in the pre-crisis period. Talks of tapering in the United States have left a few of them shaken, but not (quite) stirred.

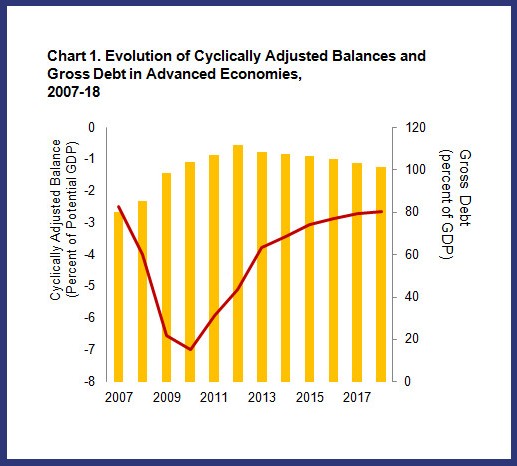

But there is still some way to go. The average debt ratio in advanced economies, although edging down, sits at historic peaks, and we project it will still remain above 100 percent of GDP by 2019 (Chart 1). The recovery is still vulnerable to several downside risks, including those stemming from the lack of clear policy plans in some major economies. The recent bouts of financial turmoil have raised concerns that the anticipated tightening of global liquidity could expose emerging markets and low-income countries to shifts in investor sentiment and more demanding debt dynamics.

Countries face varied risks

In Japan, for example, the approval of the second stage of the consumption tax rate increase next year remains uncertain, and the government has not yet articulated a medium-term fiscal strategy beyond 2015. In the United States, the bipartisan budget agreement substantially reduced near-term uncertainties, but lawmakers have yet to agree on a comprehensive medium-term plan to place the debt and public finances on a sustainable basis. And in the euro area, fiscal risks stemming from the banking sector have not been completely eliminated, and the possibility of a prolonged period of subpar growth is a growing concern.

Emerging market and developing countries, too, are fiscally vulnerable—albeit to varying degrees. A gradual build up of fiscal and external imbalances, coupled with structural factors, makes many of them susceptible to the emergence of a more challenging global environment.

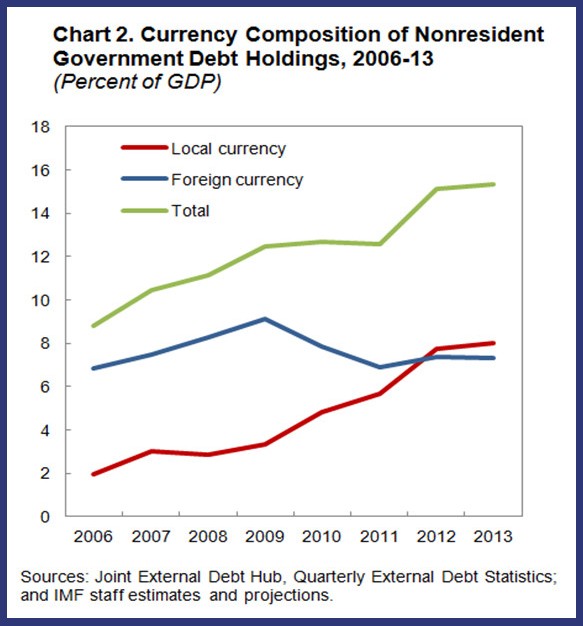

In particular, nonresident holdings of local currency debt have more than doubled since 2009 in emerging market economies, and account for sizeable shares of the debt of Hungary, South Africa, and Malaysia (Chart 2). While this is a welcome development for domestic market deepening and overall financial development, it does come with some risks. Large non-resident holdings of local currency debt strengthen the linkages between global market conditions and domestic markets and increase the responsiveness of nonresident demand for government bonds to domestic conditions, such as inflation.

Elsewhere, fiscal accounts are also coming under pressure. In low-income countries, for example, fiscal balances are some three percentage points worse than before the crisis. In frontier economies such as Ghana, Honduras, and Zambia, debt has increased without any associated increase in investment. The external environment is also becoming a lot less benign. Many low-income economies expect projected declines in commodity prices and donor aid flows to have a significant impact on the budget.

Charting a course for fiscal policy

- Advanced economies should elaborate credible and growth-friendly medium-term plans to put debt on a firm downward trajectory. In the event that downside risks to the recovery materialize, and to the extent financing allows, automatic stabilizers should be allowed to kick in. And if growth were to remain low for a prolonged period, measures to boost potential growth should be on the table.

- Emerging markets and low-income countries should rebuild fiscal buffers in order to insure against market turbulence or adverse external shocks, particularly for those countries that are currently most exposed to shifts in investor sentiment.

Policies to reduce government debt and deficits need to take into account longer-term pressures on public finances. Economic considerations suggest that spending pressures, already on the rise in many countries, will continue to build up over the coming decades.

Indeed, as countries become richer, both the demand for public goods and services and the cost of providing them increases relative to other goods and services produced in the economy. Population aging is projected to add to these increases by driving up the costs of health care and pensions. In this respect, the shift in the composition of fiscal adjustment in advanced economies towards expenditure measures is both timely and relevant. In emerging market and developing economies, too, spending pressures will need to be addressed through expenditure reform sooner or later.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3F2PeaAh5t4]