Global Financial Stability Report

GFSR Market Update

Financial System Stabilized, but Exit, Reform, and Fiscal Challenges Lie Ahead

Systemic risks have continued to subside as economic fundamentals have improved and substantial public support remains in place. Despite improvements, financial stability remains fragile in many advanced countries and some hard-hit emerging market countries. A top priority is to improve the health of these banking systems so as to ensure the credit channel is normalized. The transfer of financial risks to sovereign balance sheets and the higher public debt levels also add to financial stability risks and complicate the exit process. Capital inflows into some emerging market countries are beginning to raise concerns about asset price and exchange rate pressures. Policymakers in these countries may need to exit earlier from their supportive policies to contain financial stability risks. For all countries, the goal is to exit from the extraordinary public interventions to a global financial system that is safer, but retains the dynamism needed to support sustainable growth.

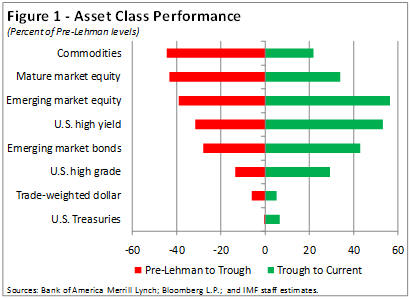

Financial markets have recovered strongly since their troughs, spurred on by improving economic fundamentals and sustained policy support (see the World Economic Outlook Update, January 2010). Risk appetite has returned, equity markets have improved, and capital markets have re-opened. As a result, prices across a wide range of assets have rebounded sharply off their historic lows, as the worst fears of investors about a collapse in economic and financial activity have not materialized (Figure 1).

These favorable developments have resulted in an overall reduction in systemic risks. Overall credit and market risks have fallen, reflecting a more favorable economic outlook and a reduction in macroeconomic risks, together with support from accommodative monetary and financial conditions. Emerging market risks have also fallen. Prevailing easier monetary and financial conditions, while helpful, also point to future challenges that will need to be managed carefully.

Even with overall improvement, however, the repair of the financial system is far from complete, and financial stability remains fragile. There are still pressing challenges from the crisis. At the same time, new risks are emerging as a result of the extraordinary support provided by the policy measures that have been implemented. Indeed, unprecedented policy support has come at the cost of a significant increase of risk to sovereign balance sheets and a consequent increase in sovereign debt burdens that raise risks for financial stability in the future. Simultaneously, some major emerging market economies already have rebounded strongly, raising initial concerns about upward pressure on both asset prices and exchange rates. As a result, the timing, sequencing, and execution of exits to a newly reformed financial system will require policymakers’ deft handling.

Banks and Credit

The first major challenge is to restore the health of the banking system and of credit provision more generally. For this it is necessary that the deleveraging process under way in the banking system remains orderly and does not require such large adjustments that they undermine the recovery. The process of absorbing the credit losses is still under way, supported by ongoing capital raising. Our estimates of expected writedowns will be updated in the April 2010 GFSR; the recovery in securities prices on banks’ balance sheets suggests the estimate would be somewhat lower than estimated previously if recalculated at the present time.

Looking forward, even though some bank capital has been raised, substantial additional capital may be needed to support the recovery of credit and sustain economic growth under expected new Basel capital adequacy standards, which appear to be converging to the markets’ norms that were the basis of the October 2009 GFSR’s calculations of remaining capital needs.

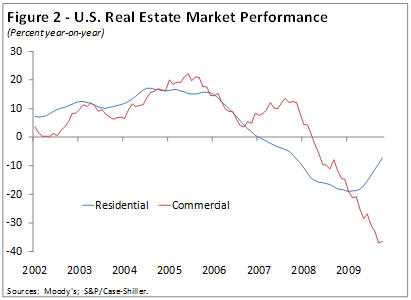

Credit losses arising from commercial real estate exposures are expected to increase substantially (Figure 2). The expected writedowns are concentrated in countries that experienced the largest run-ups in prices and subsequent corrections and are in line with our previous estimates.

Banks not only face the task of raising more capital, but also need to address potential funding shortfalls. As noted in the October 2009 GFSR, there is a wall of maturities looming ahead through 2011–13. This bunching of financing needs is a legacy of shortening maturities during the crisis. A future retrenchment in confidence therefore could severely weaken banks’ ability to roll over this debt.

A more imminent concern is the withdrawal of special central bank liquidity facilities and government guarantees for bank debt. While the use of both types of programs has fallen as money and funding markets have stabilized, some banks remain more dependent than others on such support. Unless the weaknesses in these banks are addressed in conjunction with the withdrawal of funding support measures, there is the risk of renewed bank distress and overall loss of confidence that could have systemic implications.

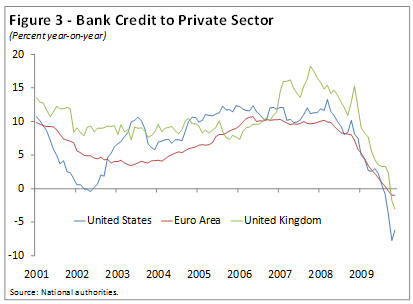

Bank credit growth has yet to recover in mature markets, despite the recent improvement in the economic outlook (Figure 3). Bank lending officer surveys show that lending conditions continue to tighten in the euro area and the United States, though the extent of tightening has moderated substantially. Although credit supply factors play a role, presently weak credit demand appears to be the main factor in constraining overall lending activity.

Bank credit growth is continuing to contract as the credit cycle turns. Even though the cycle trough is approaching, the prospects for a strong rebound are highly uncertain. Nonbank sources of credit such as corporate bond issuance have picked up strongly, but in many cases are not large enough to offset the decline in bank lending and have, for the most part, been used for refinancing outstanding debt. The improving economic outlook will bolster both the demand for credit and banks’ willingness to lend, but as banks continue to deal with capital and funding challenges, their capacity to lend may become a more binding constraint. Uncertainty about the future regulatory framework may also weigh on bank lending decisions.

A combination of continued bank writedowns, funding and capital pressures, and weak credit growth are expected to limit future bank profitability. This highlights the need for more decisive steps to promote bank restructuring in order to ensure that banks have sufficient margins to weather future shocks and to generate additional capital buffers.

Emerging Market Inflows

While bank flows to emerging markets have yet to recover, the rebound in portfolio inflows has supported a rally in emerging market assets, particularly equities, and to a lesser extent real estate. Concerns have been raised that these inflows can lead to asset price bubbles and put upward pressure on exchange rates. This can complicate the implementation of monetary and exchange rate policies, especially in those countries with less flexible exchange rate regimes.

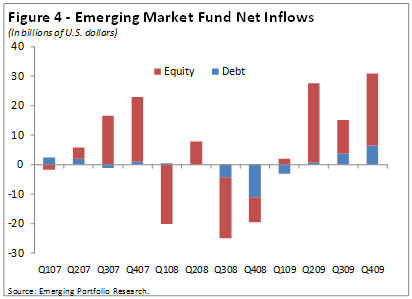

These inflows are being driven by a variety of factors. The initial surge in inflows in the second quarter of last year appears to have been the result of push factors, that is, changes in the desires of investors (Figure 4). There was a sharp renewal in risk appetite that benefited all risky assets. Investors shifted from safe havens in search of yield, given low interest rates in advanced countries. This can be seen from the decline of the dollar and treasury bond prices, and outflows from money market funds. But since the second quarter, inflows have been sustained by pull factors, namely the better growth prospects for emerging markets, particularly in Asia and Latin America. Expectations of exchange rate appreciation in these regions also have encouraged new inflows.

The rise in asset prices cannot yet be considered excessive and widespread, although there are some countries and markets where pressures have increased significantly. Property price inflation is within historical norms, with a few localized exceptions.

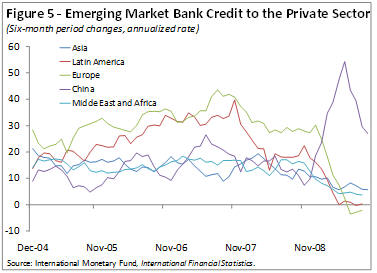

Further, outside of China, credit growth in many emerging markets has yet to recover appreciably (Figure 5). This suggests that leverage is not yet a key driver of the rise in asset prices. That said, policymakers cannot afford to be complacent about inflows and asset inflation. As recoveries take hold, the liquidity generated by inflows could fuel an excessive expansion in credit and unsustainable asset price increases.

Sovereigns Under Pressure

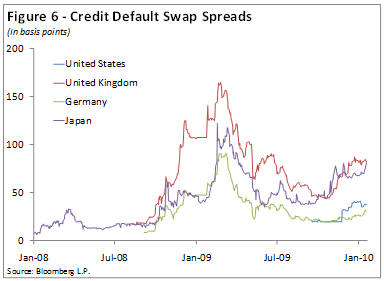

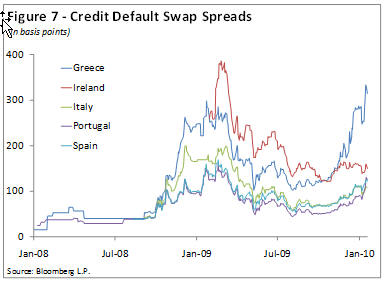

Financial market participants are increasingly focusing on fiscal stability issues among advanced economies. Concerns over sustainability and political uncertainties have led to a widening of credit default swap spreads for the United Kingdom and Japan in recent weeks (Figure 6). Other European issuers, most notably Greece, have come under more pronounced pressure after their ratings were downgraded or as uncertainty has persisted over their fiscal imbalances and consolidation plans (Figure 7).

Our projections of the net supply of public sector debt show a substantial increase in issuance relative to the long-run average over the next two to three years. This increase in deficits and public debt imposes some important challenges for policymakers and risks for financial stability.

At a minimum, there is a risk that the public debt issuance in the coming years could crowd out private sector credit growth, gradually raising interest rates for private borrowers and putting a drag on the economic recovery. This could occur as private demand for credit recovers and as banks are still constrained in their ability to extend credit, particularly as financial support measures are being unwound. A more serious risk is from a rapid increase in interest rates on public debt. Such a rapid run-up in rates and a steepening of the yield curve could have negative effects on a wide variety of financial institutions and on the recovery as sovereign debt is repriced. Finally, there is the risk of a substantial loss in investor confidence in some sovereign issuers, with negative implications for economic growth and credit performance in the affected countries. While this may be a localized problem, there is the risk of wider spillovers to other countries and markets and a negative shock to confidence.

Policy Priorities

Policymakers now face a difficult balancing act in judging the timing, pace, and sequencing of exit policies, both from the monetary and financial policies, as well as starting implementation of a medium term strategy for fiscal consolidation and debt reduction. Withdrawing policy support prematurely would leaves the financial system vulnerable to a re-intensification of pressures (such as in countries with weak recoveries and remaining financial vulnerabilities), while belated withdrawal could potentially ignite inflationary pressures and sow the seeds for future crises (such as in countries with risks of financial excesses and overheating).

In the near term, policies should be focused on securing financial stability, which remains fragile, to ensure that the recovery is maintained and that there is no recurrence of the negative feedback between the real economy and the financial sector. In those economies where financial vulnerabilities persist, efforts should continue to clean up bank balance sheets, ensure smooth rollover of funding, and restructure weak banks.

In those emerging market countries that are recovering rapidly, the policy priorities remain to address capital inflows through macroeconomic policies, including through greater exchange rate flexibility, and prudential measures.

Over the medium term, policies should be aimed at entrenching financial stability, which will underpin strong, sustained and balanced global growth. Public sector risks will need to be reduced through credible fiscal consolidation, while risks emanating from private financial activities should be addressed by the adoption of a new regulatory framework.

The Financial System of the Future

Overall, the exit from the extraordinary support measures implemented in the crisis must be to a financial system that is safer as well as sufficiently dynamic and innovative to support sustainable growth. Achieving this correct balance between safety and dynamism will not be easy.

Several aspects of implementation require special attention. Policymakers should be mindful of the costs associated with uncertainty about future regulation, as this may hinder financial institutions’ plans regarding their business lines and credit provision. But they should also avoid the risks associated with too-rapid deployment of new regulations without proper overall impact studies. It also continues to be vitally important that differences in international implementation of the new regulatory framework are minimized to avoid an uneven playing field and regulatory arbitrage that could compromise financial stability.

For regulatory reform to be successful, micro- and macro-prudential regulations will have to complement one another and help to effectively mitigate systemic risks. Only then can the financial system properly do its job—to intermediate flows from savers to borrowers in ways that enhance sustainable economic growth and financial stability.